America's book-burning moment: Offended parents can protest, but they shouldn't censor | Miraldi

The headline is two lines long, centered over a one-column story in the New York Times on May 10, 1933: “Nazi book-burning fails to stir Berlin.” A second headline adds: “Un-German literature is consigned to the flames.”

The story recounts how 40,000 people gathered in the German capital, opposite a university, to watch student groups ceremoniously orchestrate a bonfire to burn books by lightweight authors such as Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Berthold Brecht and Thomas Mann. The German propaganda master, Joseph Goebbels, addressed the throng, applauding the students’ “strong, great and symbolic deed.”

“You do well to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past,” he declared to cheers.

We all know, of course, where the book burnings led, where the effort to blot out ideas some did not like carried Germany — and the world. I won’t suggest that America is at the book burning stage, but it is getting worrisome — and closer.

I fear our headline will soon read: “Attempts to ban books in many states fails to stir Americans.”

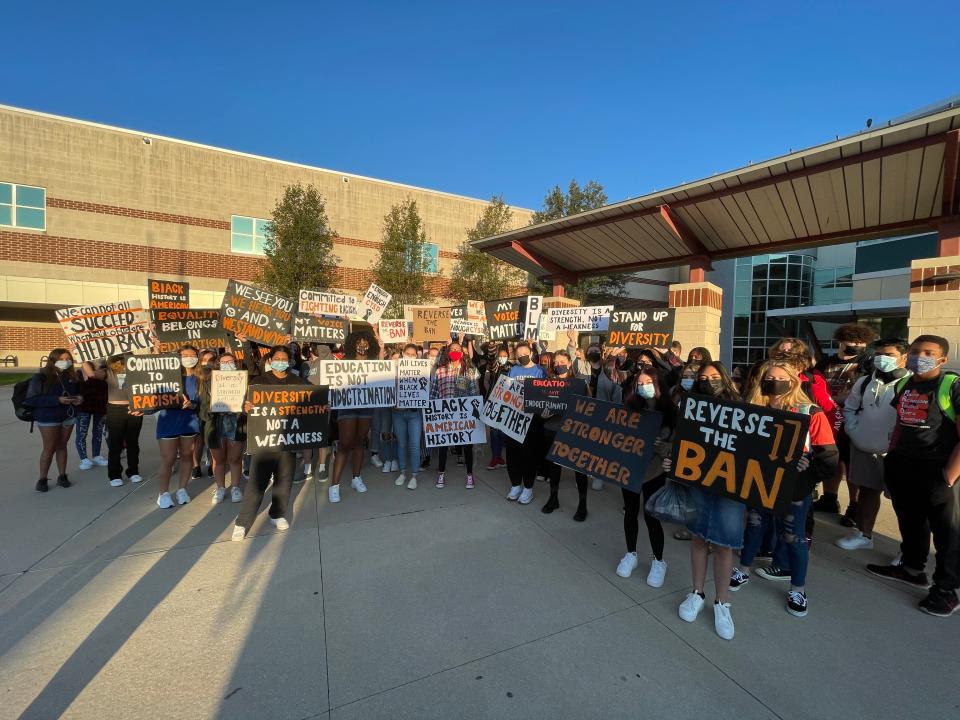

The American Library Association cited 330 banning attempts last fall, a “tsunami of book challenges reaching libraries across the country.” Almost all were about race, gender and sexuality — what the ALA called an “unprecedented” demand for censorship in public schools that America has not seen since the 1980s.

Some of the books are renowned and famous — “Of Mice and Men” and “To Kill a Mockingbird,” for example. Some are contemporary and critically acclaimed, aimed at young people: Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Fences,” and Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower.”

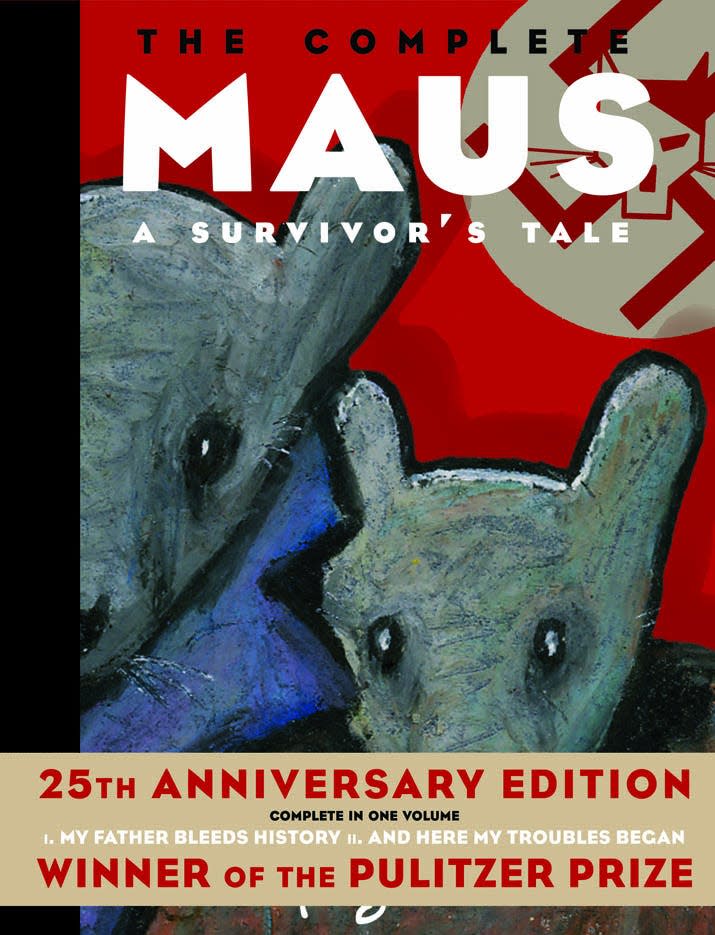

The most startling example is “Maus,” a haunting Pulitzer-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, banned by a Tennessee school district in January because it contained swear words and drawings of nudes. The book's author, Art Spiegelman, conceded the book has “disturbing imagery. But you know what? It’s disturbing history.”

In Wyoming, a prosecutor is considering filing criminal charges against school librarians for simply choosing certain books. In Texas a state legislator suggested 800 books for a “watch list,” most dealing with race and LGBTQ topics. To be clear, they are simply soldiers in America’s culture war — trying to stop young people from hearing about issues they want to blot out. After all, no one is really gay or transexual. America never enslaved and discriminated against blacks. Why read about it?

Put it all together — it is really hitting a crescendo right now — and we are at a book-burning moment.

In fact, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, population 140,000, two school board members urged burning a number of offensive books.

"I think we should throw those books in a fire," one said, with the other adding, let’s “see the books before we burn them so we can identify within our community that we are eradicating this bad stuff."

“The truth itself is under attack,” writes Richard Ovenden in his timely 2020 book, “Burning Books.”

But this is not just an American phenomenon. The urge to purge has a long history.

As Ovenden points out, “the preservation of knowledge is a crucial struggle all over the world.”

USA TODAY books editor: You should care more about the ‘Maus’ book ban than any Joe Rogan controversy. Here's why

More Miraldi: Can America work without a robust free press? Journalism needs a bailout

But surely it is rearing its ugly censorship head now — from Texas to Tennessee, from Florida to New Jersey.

I first collided with the authoritarian proclivity to censor in 1968 when my own father tried to get a book my class was reading banned. I was 18 years old in an honors-level English class in which the teacher assigned a dozen non-traditional books that weren’t part of the normal reading curriculum.

My father, who was not college educated but very smart, an old-fashioned Eisenhower Republican and a very religious protestant, read many of the assigned books.

One rubbed him wrong — Claude Brown’s 1965 “Manchild in the Promised Land,” a gritty coming-of-age novel about a slice of black life in 1950s Harlem. The acclaimed book has a lot of cursing and sexual activity. It often lands on banned book lists.

My father marched to see my teacher, an articulate woman who showed my father why it made sense in an era of great civil rights unrest. A progressive on race matters, my father was convinced — and charmed by her explanation. The point: parents have long objected to books that don’t meet their parochial, prudish and sometimes bigoted views of the world.

And they have the right to protest — but not censor.

“Manchild” would be problematic still today because it dredges up a time of oppression in the black community, forcing America to confront once again its bigoted history. But the attempt to bury this history goes beyond book banning.

Last year 66 pieces of state legislation were proposed that would prohibit teachers from even discussing certain topics.

The goal: “Terrify educators into thinking twice about how they discuss race, sex, and American history,” writes Jeffrey Sachs of PEN America, which defends writers and creative expression.

The proposed laws signal “a willingness to strong-arm teachers into ideological conformity,” Sachs said.

The First Amendment was not meant to be a tool of public opinion. The public does not get to vote on what opinion it will allow — or what book can be published. Books are protected speech, not at the whim of a parent whose politics are offended by black history or gender sexuality.

But this does not mean that schools should not have a clear process of which books they choose and why. It’s just that once a book is in the library, it should remain there. The Supreme Court said as much in a 1982 case that concluded the First Amendment protects not only the right to express ideas, but also the right to receive them.

The bigger question of course, is why, why, why? Why are people so afraid of ideas and cultures with which they disagree?

Certainly, some of it comes from racism and homophobia and the inability to talk about human sexuality. Americans watch a lot of pornography but don’t have many talks with children about the hormones behind it all.

In the end, freedom of speech gets caught up in the crosshairs:

Does the First Amendment protect the transmission of ideas and language suitable for adults but perhaps not for children?

Where is that line drawn?

And who draws the line?

When are young people even eligible for the protections of the Constitution?

Answering those questions is important; more important is what Jayson Reynolds, an African American poet and author of eight novels who has landed on banned book lists, explains:

Books “ground us in our humanity; they convince us that we’re not actually that different and that the things that are actually different about us should be celebrated because they are what make up this tapestry of life.”

Stop worrying about protecting children from ideas. Let them embrace new, different and even discomforting ideas. That is how they will grow. Open books, don’t burn them.

Rob Miraldi’s writing on the First Amendment has won numerous state and national awards. He teaches journalism at SUNY Paltz.

Twitter: @miral98

Email: miral98@aol.com

This article originally appeared on Poughkeepsie Journal: Banned books in the U.S.: We must stop censorship | Miraldi