America's public servants are being terrorized with death threats. The 'emotional toll' is lasting.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Lydia Kou was in the midst of a Palo Alto City Council campaign when the first chilling call came in last year.

An angry voice railed against her position on a hotel project, then launched into a tirade of nasty sexual remarks. Kou hung up, disgusted and frightened. But the caller persisted, leaving a series of harassing voicemails, even enlisting someone else to help.

Then, after more than a week's silence, the man struck again with a bone-chilling message: "I'm back. I'm going to call you until you change your number. You deserve to have your throat slit."

Kou's voice broke as she relived the experience. “When I heard that message, I felt cold inside,” she said. “It still has an emotional toll. … I’m constantly watching over my back.”

In a bitterly divided nation, experts say they’re witnessing a proliferation of death threats against public servants, professionals and activists across the United States and around the globe.

Fact? Checked. Make sure you have the real story with the Checking the Facts newsletter

Election officials, public health workers, school employees, police, flight attendants, scientists, journalists and food servers are among those who have bemoaned the surge. While death threats are not tracked nationally, the escalation has been recognized from small-town police departments to the Justice Department.

In congressional sessions and academic circles, the word “unprecedented” is often used, even though no one knows how much the phenomenon has increased.

In a House Judiciary Committee hearing this month, Attorney General Merrick Garland testified about efforts to protect education officials and other public servants who are being targeted.

“It's not only about schools,” Garland said. “We have similar concerns with respect to election workers, with respect to hate crime, with respect to judges and police officers. This is a rising problem in the United States.”

Stephen Morewitz, author of the 2008 book “Death Threats and Violence: New Research and Clinical Perspectives,” said he's certain that malicious messaging has exploded.

There is no single culprit, Morewitz said. Instead, he blames a dysfunctional social milieu – a combination of technology, politics and alienation.

The internet offers anonymity. Polarizing media and online conspiracy cults fuel passions. The coronavirus pandemic has isolated and frustrated people. And a failing mental health system means there are few places to get help.

'Terrorism' and 'hate crimes': School boards say death threats, unruly meetings require FBI

Throw in hot-button issues such as COVID-19 policies, claims of election fraud, critical race theory, abortion and the Black Lives Matter movement and the chemistry is combustible.

“Those kinds of conditions foster death threats,” said Morewitz, founder and president of the Forensic Social Sciences Association. “The underlying pathology is varied … (but) the assertion of power and control is a common denominator.

“They can’t change their lives. So they get power by terrorizing.”

When people carry out their threats

Death threats come in all shapes, sizes and methods: online posts, graffiti, phone calls, letters, texts, emails and signs.

In Florida this month, a 35-year-old man who is deaf was arrested after he allegedly texted a sign-language video message to his neighbor during a feud over missing mail: “I’ll kill you, OK? I’ll kill you.”

During the Jan. 6 Capitol insurgency, yet another means of threat transmission emerged, Morewitz said: “They were chanting ‘Hang Mike Pence.’ That’s a new kind of death threat – chanting.”

They died by suicide after the Capitol riot: That's why their names won't be memorialized

Though people who make death threats rarely carry them out, Morewitz said, the uncertainty – especially from anonymous perpetrators – magnifies fear.

And there are exceptions that validate the terror.

In September, a man in El Paso, Texas, with “extremist religious beliefs” allegedly sent a rambling manifesto to Army intelligence officials announcing that he intended to kill residents of a house next to a park where he believed satanic abortions were being performed.

According to the El Paso Times, the email, riddled with antisemitic, homophobic and anti-Joe Biden comments, was sent hours before attorney Georgette Kaufmann was gunned down and her lawyer husband, Daniel Kaufmann, was wounded.

Joseph Angel Alvarez, 38, a pizza delivery driver with no prior criminal record, awaits trial.

'This is America today'

Morewitz and others said the rise in death threats seems focused on professions associated with volatile public issues.

In Paulding County, Georgia, elections supervisor Deidre Holden received an email before the January runoff vote for Congress.

“We'll make the Boston bombings look like child's play," the author warned. "Detonations will occur at every polling site set up in this county. No one at these places will be spared.”

Holden recalls sitting in her car, looking at her phone. “A numbness went over me,” she said. That shock quickly turned into an angry resolve not to be bullied. Then fear. Holden’s glass-enclosed election office is on a first floor, next to parking lot. Police devised a plan to fill parking spaces so a vehicle bomb would be, as they explained, "far enough away to soften the blow.”

That's when the danger hit home, Holden said. “I realized, if they’re crazy enough to send something like that, they may be crazy enough to carry it out.”

From Florida to Alaska, election officials have recounted similar experiences while pleading for support.

In Arizona, former Maricopa County Recorder Adrian Fontes told the House Administration Committee this month that his team in Phoenix received 35 threats of violence as votes were counted for the 2020 presidential election. At one point, he said, he had to call a police rescue squad as crowds – some armed with assault-style rifles – screamed and banged on windows.

“This is not a story about some deteriorating, Third World democracy on the verge of authoritarianism. This is America today,” said Fontes, a former Marine.

In late June, the Justice Department announced the formation of a task force to protect election officials.

'It's changed the way I live'

Ann Levitt hadn't seen anything like it in the 45 years she has worked at schools.

In December, a woman showed up at her home and started banging on the door and shouting obscenities because she was furious that schools were closed because of COVID-19 restrictions. “She said I was the devil and just all kinds of things,” said Levitt, superintendent of Savannah-Chatham County Public School System in Georgia. “I called the police. They came, looked around, didn’t see anyone, didn’t do much.”

Levitt said she installed a security system, got her address removed from websites and abandoned Facebook. “I don’t go to my car unescorted at night," she said. "It’s changed the way I live.”

Shouting matches, arrests and fed-up parents: How school board meetings became ground zero in politics

Even when a threat is not explicit, public servants may be reasonably terrified.

In a meeting of the Poway Unified School District board in San Diego County, NPR reported, a group of anti-maskers barged into the building, yelling at staffers. Trustees immediately adjourned their session, whereupon the demonstrators marched into the board room, announced they were taking over, held a vote and declared themselves officeholders.

“We’ve seen a record number of superintendents stepping down this year,” said Daniel Domenech, executive director of the School Superintendents Association. “It’s because of the stress on them and their families, the abuse and threats."

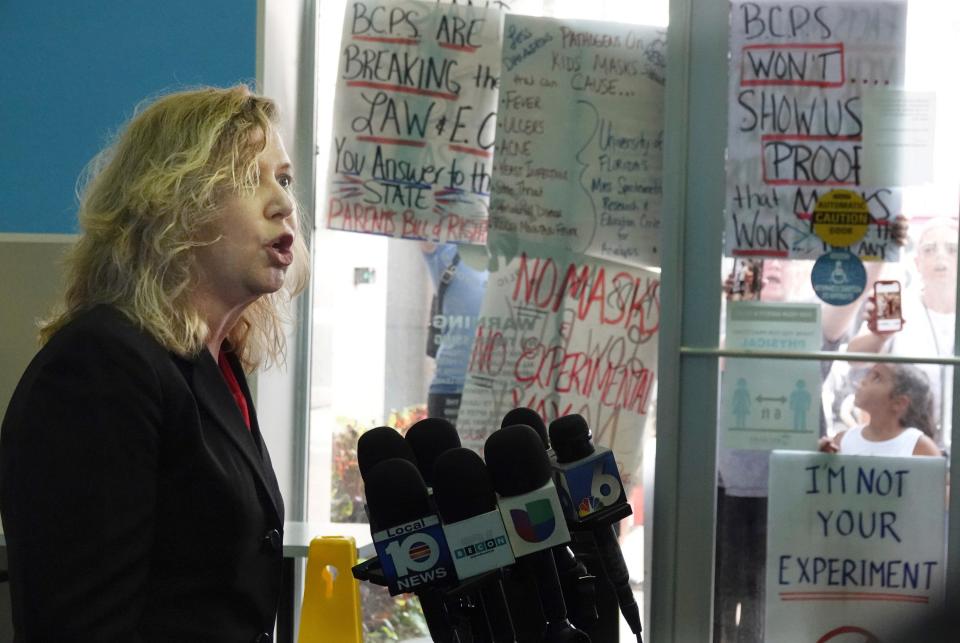

In September, the National School Boards Association called for help from the Biden administration, asserting in an open letter that educators at 14,000 public schools are “under an immediate threat” as they carry out pandemic policies and contend with false claims over critical race theory.

This month, Garland directed the FBI and U.S. attorneys to develop a strategy to combat the harassment, intimidation and threats.

'There is a sickness in America ...'

In Flathead County, Montana, deputies advised public health officer Tamalee St. James Robinson that a man had written a letter asking the sheriff to provide weapons and venue so he could confront her in a duel. St. James Robinson said the man, whom she had never met, wanted to prove that she “would go to the length of killing someone to carry out the mitigation measures” for COVID-19.

There was no gunbattle. St. James Robinson, overwhelmed by hostile Facebook posts, hate mail, protests outside her office and the workload of the pandemic, resigned.

In a survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this spring, nearly a quarter of the public health employees who responded said they had been “bullied, threatened or harassed” because of their work, and 12% received job-related threats.

“Luckily, they haven’t maimed or killed anybody,” said Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs for the National Association of County and City Health Officials. “But it’s not just words.”

In testimony last month to the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, Beth Resnick, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said her team had identified at least 1,500 incidents of attacks and harassment against health workers and departments across the country.

Half of the community health departments surveyed reported at least one incident – death threats, intimidation, even shots fired at their homes, Resnick said. In the face of that onslaught, at least 300 workers have quit since the pandemic began.

Two days after declaring a mask mandate in August, Adam London, director of Michigan’s Kent County Health Department, wrote an email to his board of commissioners.

According to The Washington Post, London reported that someone had shouted an expletive at him, adding, “I hope someone abuses your kids and forces you to watch!” Then, he said, a motorist tried to run him off the road – twice – at more than 70 mph.

“I need help,” London told commissioners. “There is a sickness in America far more insidious than COVID.”

Why threat-makers get away with it

Victims and those who study death threats say police often are legally hamstrung when complaints are filed, and sometimes don’t seem to treat the offense as a serious crime.

That's especially true where the threat is veiled, Morewitz said. If the perpetrator says they'd like to see the victim die, rather than announcing plans to kill, First Amendment protections often prevent prosecution.

Where the line gets drawn remains unclear because he U.S. Supreme Court has never fully defined a "true threat" and lower courts disagree.

Jeffrey James Higgins, a former law enforcement officer of 25 years who defends police, said that even overt threats may not be criminal if perpetrators claim they were joking or exaggerating. “If I just tell my neighbor, ‘I’m going to kill you,’ that’s not necessarily illegal,” Higgins said. “I have to take some kind of action.”

From our editor, to your inbox: Editor-in-chief Nicole Carroll takes you behind the scenes of the newsroom in this weekly newsletter

Even if police make an arrest, he noted, prosecutors seldom file charges when a case is murky. Thus police resort to what Higgins calls “informal policing” – questioning the suspect and typing up an informational report. “If a week later this neighbor turns up dead, they’ve documented it,” he said.

There is no data on what percentage of death threats get reported or what fraction of those are prosecuted. However, amid former President Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” campaign, Reuters identified more than 100 threats of violence against election officials in the U.S. and found only four had led to arrests. Not one resulted in a conviction.

The Reuters report focused on Staci McElyea, a Nevada election official. One day after Biden’s election victory, a man called her to complain voting was rigged, adding, “I hope your children get molested. You’re all going to f---ing die.”

Police identified the caller but decided the phone message was “protected political speech” rather than a criminal threat. According to the news service, an officer warned McElyea her complaint “might have pissed him off even further.”

Sometimes, however, people who make threats do get charged and convicted.

Palo Alto police used a search warrant and tracking technology to find the caller who said Lydia Kou should have her throat slit. Alexander Breya, 29, of Menlo Park, was arrested and convicted.

According to Palo Alto Online, Breya told investigators he was drunk when he started making calls and was “just joking" with the threat.

Breya pleaded guilty to misdemeanor harassment after a prosecutor concluded his offense did not rise to the level of a “criminal threat” because Kou was not “in immediate fear for her life,” the publication reported. A judge ordered him to do community service and attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

Kou told USA TODAY she has chosen to be open about her trauma because she and other victims have done nothing wrong.

“It’s not our fault. We should talk about it,” Kou said. “And I want them (perpetrators) to recognize what they’ve done, to understand the pain and fear.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: America's public servants under attack, terrorized by a divided nation