In America's suburbs, elections are a fight for the soul of local school districts

INDIANAPOLIS − Other than being a touch warmer than it should be in late September, Juanita Albright had herself another perfect afternoon to knock on doors in Fishers, Indiana. It’s the 18th straight day – there was a rainstorm 19 days ago – that the candidate vying for a seat on the local school board has walked the sprawling subdivisions that blanket the Indianapolis suburb.

Armed with campaign flyers and an iPhone, open to the app she’s using to track which houses she and her volunteers visit, Albright starts down a quiet street in the aptly-named Sunblest neighborhood.

A little before 5 p.m., Albright expects some residents won’t be home from work yet, in which case she will just tuck into their door. But, at the very first house, she strikes the equivalent of door-knocking gold. Not only does the older man who answers take her flyer, he asks for a yard sign.

“We need more people like you,” he tells her. “God bless you.”

Albright’s running on the idea that the school district – Hamilton Southeastern Schools – needs to refocus its attention on academic excellence, become more transparent with families and commit to fiscal responsibility.

The message seems to be resonating with the folks in Sunblest. Everyone who answers takes a flyer. Another house already has a “Vote Dr. Juanita Albright” sign in their lawn.

The internal medicine physician says she was inspired to run after schools were shuttered in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Parents were able to see first-hand what our children were being taught,” she says on her campaign website. Albright said she and her husband wanted to pull their youngest children, twin boys in the 10th grade, out of the public school system.

“We were so concerned about what was going on,” she said during a recent campaign fundraiser. “And yet, they had friends. They loved where they were. So, we said, ‘OK, we’ll let you stay. But we’re going to be watching.’”

Her platform probably sounds familiar. It’s not unlike what other candidates are running on in suburban communities across the country – places where parents packed school board meetings last summer over fear that their children might be forced to wear a mask, rumors that teachers were indoctrinating students with leftist ideology and anger that lessons about white privilege could make their children feel bad about the color of their skin.

In these pockets of relative affluence where families are predominately white, a new crop of school board candidates have emerged with promises to “take back” their public school systems. They’re appealing to voters with platforms that would sound good to any parent: Academic excellence! Parental involvement! Students first! Transparency!

Who doesn’t want an excellent school for their child?

What isn’t always said, though, is how candidates define “academic excellence” or other campaign promises. In many cases, the words and phrases found across the platforms of conservative candidates are the new buzz words of right-wing opposition to diversity, equity and inclusion work that many schools had been doing but undertook with new fervor in 2020, after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.

Over the last year, conservatives were railing against social and emotional learning, “obscene books” and critical race theory – a framework developed by legal scholars to discuss how racism is built into American society that isn’t taught in K-12 schools. Now, many of those same voices are promoting academic excellence, parental rights and curriculum transparency.

Should conservatives win the majority on local boards, they will gain the power to change the public school experience for thousands of American children.

Changing demographics fuel fear

“The real motivator is a change in the racial and ethnic dynamics in American society,” said Kevin Brown, the Mitch Willoughby Professor of Law at the University of South Carolina School of Law. “As our society changes and becomes more diverse, the kind of material we present to our students has to take that into account.”

For the last two years, Brown has worked to correct the right-wing narrative that critical race theory is being used to indoctrinate the nation’s public school children. He was part of the first Critical Race Theory workshop, held in 1989. The framework was developed, he said, to explain the struggles of Black people in America and address the systemic racism baked into the county’s legal system.

What suburban white America has a problem with is not just CRT, he said, but the way the country’s demographics are shifting.

“In part, it’s an attack on CRT but also an attack on the changing racial dynamics in American society,” Brown said. “(They’re saying) we want to go back to a time when we didn’t have to deal with all this diversity, when all these people of color who are in the country now aren’t in the country.

“The problem is it’s too late to do that.”

It’s also why conservative messaging about a “return to academic excellence” seems to be particularly potent in America’s suburban communities – places where the population tends to be wealthier and whiter than neighboring urban centers. Built on white flight decades earlier, many of these communities now seem to be driven by white fright – fear over what America’s changing demographics and ongoing reckoning with its racist past and present will mean for their future and that of their children.

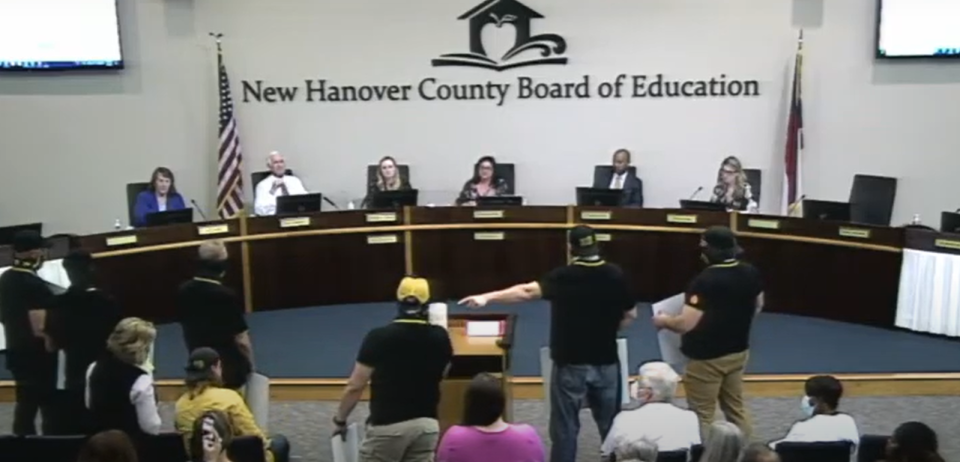

In New Hanover County, North Carolina, which includes Wilmington, and where 82% of residents are white according to census data, critical race theory also has become a flashpoint.

For months this year, parents have shown up in droves at school board meetings to complain about a new social studies curriculum and “marxist indoctrination.”

The superintendent has defended the district repeatedly, and offered parents the chance to report to him if they believe CRT is being taught in his school system, asking for specifics: the subject, class and lesson plan.

As a result, this year’s elections, which are partisan, are drawing new sorts of involvement and advocacy. One new group that says it represents parents backs a slate of candidates, including one sitting member, they hope will create a conservative majority on the board.

“There is no greater current fight than to protect our impressionable children from the woke ideologies of the left,” the Tide Turners group says on its website.

In Ottawa County, Michigan, a local PAC has vetted 11 school board candidates who are running in five school districts. The Ottawa Impact Educational PAC asks candidates to sign a nine-page contract for school board candidates, which lists promises such as upholding the Constitution as a school board member, rejecting academic frameworks like critical race theory and opposing the "over-sexualization of children."

Ottawa County is a suburban slice of Michigan, with Grand Rapids to the east and Lake Michigan to the west. Census data shows 92 percent of residents are white.

Eight of the candidates the group vetted for county commission seats won their primaries earlier this year.

In Florida, where school board races are nonpartisan, controversial Gov. Ron DeSantis is working to elect conservative school board candidates. He issued endorsements, spent his own campaign funds and toured the state to promote his preferred candidates ahead of that state’s August primaries. And he was largely successful, with 25 of his 30 endorsed candidates winning or advancing to a runoff. He helped elect conservative majorities to school boards in at least two large counties that serve roughly 175,000 children.

A conservative-learning PAC in Texas elected a slate of candidates to a wealthy district in Austin and, in a nearby suburban community, 17 people have filed to run for five seats. Among them are a slate of conservative candidates aligned with two board members that have been at odds with the rest of the board – going so far as to file a lawsuit against the other board members. The suit was dismissed earlier this year.

Suburban phenomenon

Many of the candidates and their supporters say they long to return to a "simpler time" – one where white people and, in particular, white children, weren’t forced to reckon with the sins of the past and, however passively, enjoyed the privilege that came with being part of the majority.

And it's likely why the same narratives that are spreading like wildfire across suburban America are failing to catch on in the urban centers they're built around, where communities are more diverse and where many of the non-white children that make up the majority of the country's public school population are educated.

Look at Hamilton County, Indiana, a near-perfect illustration of this trend. Sitting just north of Indianapolis, it’s home to some of the wealthiest communities in the state. According to census data, it’s 85% white. And this election cycle, it has got some of the most heavily contested school board races in the region. The four largest school districts in the county each have a slate of candidates running together with hopes to usher in a new, conservative majority.

Over the last two years, each has played host to hours-long school board meetings, to shouting matches about masks and library books and racial equity initiatives. They’ve had to shut down rumors about litter boxes in school bathrooms for students dressed as cats. Police had to escort a pediatrician out of a meeting of one of the district’s school boards after a woman tried to follow the doctor to her car, shouting about how she was in the pocket of the pharmaceutical companies. Another district suspended public comment and moved to virtual meetings for several months after a handgun fell out of a man’s pocket during a meeting.

Meanwhile, just a few miles south, school board races look very different. The 11 districts in Indianapolis and the surrounding county have very few contested races and most incumbent school board members are running against very few challengers.

The Indianapolis Public School district, the state’s largest, has three seats up for election but only one of those is contested. The issues suburban candidates are talking about − CRT, SEL, parents' rights − haven't come up. Instead, the biggest issue for those candidates is a redistricting proposal that district leaders have rolled out in an effort to make good on promises made two years ago when that board adopted a “Black Lives Matter” resolution.

With a student body that’s nearly 75% non-white, Indianapolis Public Schools is the inverse of its neighbors to the north. Most of its students come from low-income homes. The district admitted, though, that for years it was catering to a small share of white and wealthy families at the expense of the majority of students it serves.

It committed to change.

“When we adopted that policy in 2020, it was not just to have nice words to say in a moment that seemed to require them,” IPS Superintendent Aleesia Johnson said, “but to really, publicly, name what is important to us, which I also think serves as a mechanism of accountability for us.

“We are telling our community, ‘this is what we value, what's important to us,’ and it can't just be words. It needs to require action.”

The redistricting plan would change the grade configuration in schools and end student assignment policies that effectively shut out Black and brown students from some of the district’s highest-performing elementary schools. Johnson said that, two years later, IPS remains committed to racial equity.

That is, despite, the political winds shifting around it.

Last year, Indiana’s attorney general directed public schools to treat the Black Lives Matter movement as a political group.

Attorney General Todd Rokita issued an advisory opinion on how schools should treat BLM, at the request of two state lawmakers. Sen. John Crane, R-Brownsburg, and Rep. Michelle Davis, R-Whiteland, requested the opinion amid concerns about the politicization of students’ education and what Davis called the “controversial ideology” of BLM.

The opinion came after months of debate in school districts around the state. One of Hamilton County's school districts had, earlier that year, ordered items be removed from the classroom that could be deemed “political” including Black Lives Matter signs and pride flags after complaints were made.

In IPS, though, Johnson said nothing has changed.

"When we say that Black lives matter, we are talking about black people, not the political organization," she said. "Black people, their lives matter. In 2020, that needed to be affirmed explicitly. That was the position that we took and that is still true."

'You people can leave'

While debates over CRT, book banning, indoctrination, preferred pronouns, furries and other right-wing conspiracy theories have been swirling through the school districts of suburban Indianapolis for the last year-and-a-half, nearly identical concerns have popped up in other suburban communities around the state.

In northern Indiana, some educators are preparing a “Plan B,” in case conservative-learning candidates are elected to their school boards.

Three candidates running for four open seats in the Penn-Harris-Madison school district, a wealthy suburb to South Bend, Indiana, have been endorsed by local group Strengthen Our Schools. The group has a history of reading from books they deem inappropriate at public school board meetings, advocating for the firing of key administrators and board members and pushing for the removal of CRT-infused lessons that administrators say don't exist. The constant scrutiny of lessons, curriculum and educators’ personal opinions expressed outside of school has already put pressure on staff.

With one sitting board member already calling on the district to ban CRT, educators within the northern Indiana community say they can only take so much. Lisa Langfeldt, president of the district’s teachers union, said she’s told teachers not to come to board meetings as conservative parents turn their attention to issues like book bans and the use of students’ preferred pronouns. She and others fear teachers will leave if the board turns.

“I worry all the time,” Langfeldt said. “The same teachers that are going to take a bullet for their child, if you can’t trust them to read a picture book, what trust do you have?"

More than 300 miles away, at the southern end of the state, a candidate for school board in Evansville wrote an article last year for a local conservative Christian publication in which she said: "Those who seek to destroy this nation are 'grooming' our children through indoctrination in the education system."

Carolyn Gallagher is among five candidates running for an open at-large seat in the Evansville Vanderburgh School Corporation. She believes that the district is teaching CRT. She has not provided evidence of that claim, though, and the district has said it does not teach CRT.

"They are using these theories to reshape the thoughts children have about different races," she said. "They are teaching our children that we should be ashamed of being white. That we need to apologize for our skin color."

Gallagher said she doesn’t believe systemic racism exists in America.

This belief, though, and desire to return to a time in which schools were solely focused on academics ignores the experiences of people of color, Brown said. The "good 'ol days" many conservative candidates and their supporters yearn for were not so good for Black and brown people.

"The reasons they weren’t good days for Black people was of the embedded racism in American society at the time," Brown said.

At a recent campaign fundraiser for Albright and the three other candidates she's running with in a bid to win the majority of seats on their board, a state legislator is the keynote speaker. State Rep. Chris Jeter, R-Fishers, is talking all about the good ol’ days, when there were still gravel roads around town.

Today, the suburb has a population of roughly 100,000 people.

He graduated from the district decades earlier, when it was one of the best in the state, he said. Last year, it was only 16th best on the state's standardized tests. That means the district is still in the top 5% statewide.

Still, Jeter said it's time for new leadership. He applauded the lone conservative now on the board for her vote against hiring the district's new superintendent, the first Black woman to lead the district and told the candidates hoping to join her that supporters would stand with them when they had to do difficult things, such as dealing with "a diverse front office."

Jeter said people have often encouraged him and his wife to send their children to a private Christian school nearby.

“We just can’t bring ourselves to do it,” he said. “I think about Ronald Reagan, in that famous debate when they tried to take the microphone away from him. He said, ‘I paid for this microphone.’

“I paid for these schools. I’ve been in this system 40 years. I’m not leaving. You people can leave and we’re gonna make ‘em leave, come November.”

IndyStar reporter Caroline Beck, South Bend Tribune reporter Carley Lanich, Wilmington Star News reporter Sydney Hoover and Detroit Free Press reporters Arpan Lobo and Dave Boucher contributed to this story.

Call IndyStar education reporter Arika Herron at 317-201-5620 or email her at Arika.Herron@indystar.com. Follow her on Twitter: @ArikaHerron.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Nationwide school board elections are a top target for conservatives