Amid a climate crisis, people of faith seek a deeper connection to the environment

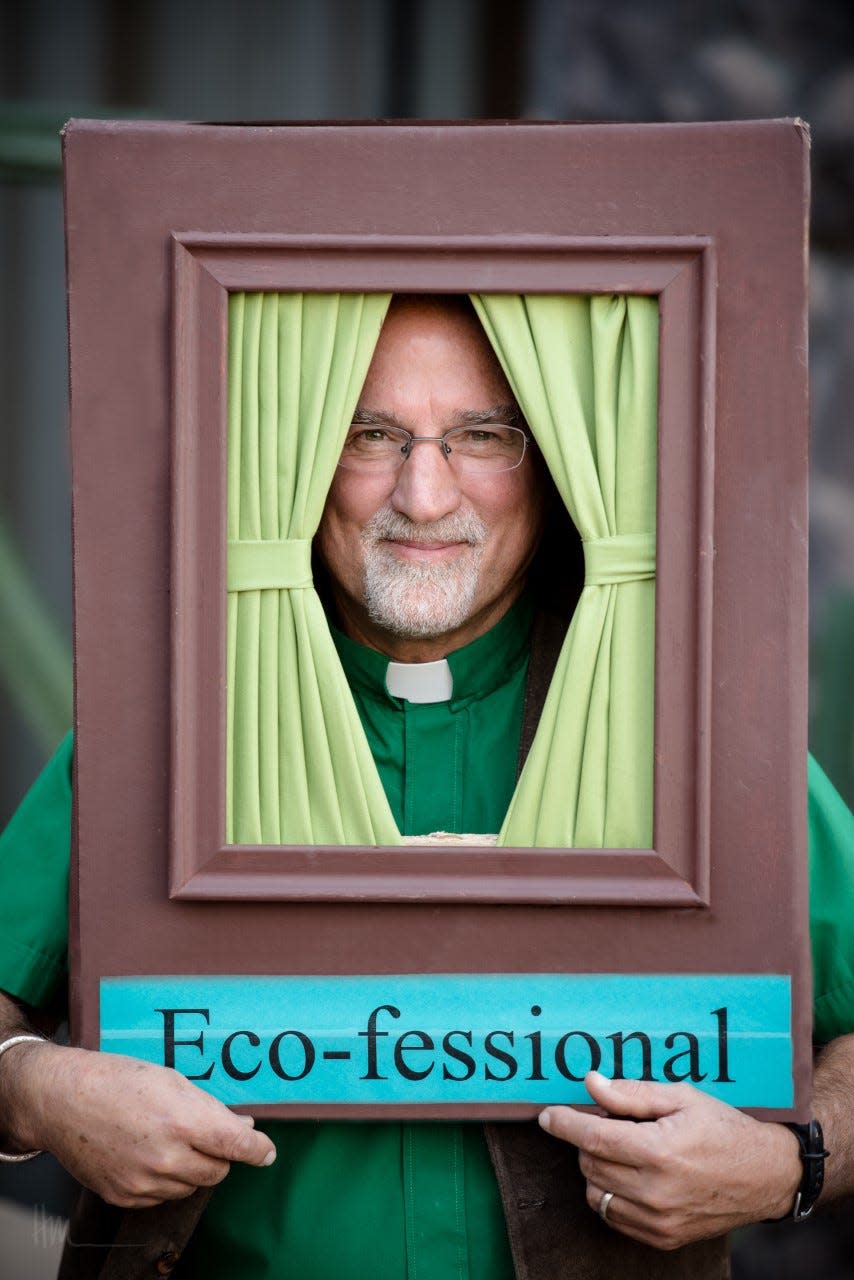

Doug Bland, the pastor at the Tempe Community Christian Church has started something he calls “ecofessionals.” He wears a cardboard box, spray-painted mahogany brown, and invites people to confess their ecological sins.

Some of his congregants say they fly too much on airplanes. Some confess they eat too much meat. Others say they don’t appreciate the environment enough.

He responds with ecological "penances": Turn off lights. Install solar panels. Drive less. Once he suggested someone “shower with a partner,” but that didn't quite work: The recipient was a Franciscan priest.

Bland is also the executive director for Arizona Interfaith Power and Light, an organization that works to bring a spiritual response to the climate crisis. The group works with about 100 congregations around the state, including churches, mosques and synagogues. It’s one of 40 chapters nationwide calling for faith leaders and communities to get involved with the climate crisis.

The group has been around for the past 12 years and members are often a fixture at rallies for climate justice. They've attended events urging Arizona Sens. Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly to pass the president's Build Back Better bill and on Environment Day at the Arizona Legislature, they usually lead a spirit circle.

This holiday season, The Arizona Republic sat down with members of Arizona Interfaith Power and Light to learn about the meaning behind their motivations and to ask: What do their faith traditions say about the environment?

'Red alert': Lake Mead falls to record-low level, a milestone in Colorado River's crisis

Lost connection to the natural world

Bland grew up hiking and camping with his family. He says he feels closest to the divine when he's outdoors. For many in his church, he said, it’s the same.

For the years he's served as a pastor, Bland has asked his congregation when they feel closest to God.

"'And not one time did they ever say, ‘Pastor, I feel closest to God during your sermons,’” he said. “Instead, they say 'on top of the mountain,' or 'at the ocean,' or 'camping by a stream' or 'hiking in the desert,' or whatever.”

He has called the climate crisis a symptom of a larger problem: The recent disconnect with nature.

“The real problem is broken relationships between human and human, and between human and nature,” he said. The writers of scriptures “were mostly agrarian people who knew that they were dependent on the earth and good harvest. And it's only in recent years, in the last 150 years, that we have really been so separated from the earth. We’re urban people, we hardly noticed the phases of the moon.”

Ahmad Shqeirat, who formerly served as the imam of Islamic Community Center of Tempe, wrote a paper about environmental ethics in Islam. In the paper, he says the earth is a sign of God’s greatness.

“The Qur’an uses the earth, and the whole universe, as clear evidence of the existence of God, a screen to display, or a field to show His most beautiful names and perfect attributes in function, as well as the best way to know and understand Him,” he wrote in the paper, citing verse 88:17.

Forest Service was supposed to protect: Instead, water users drain untold amounts

This land is not our land

Several people from different faith traditions talked about how the earth belongs to the divine. Bland referenced Psalm 24:1-2, which states, “The earth is the Lord’s.”

Nona Siegel, a Jewish member of Arizona Interfaith Power and Light, grew up in Montana, where she became aware of several mining projects. One of Judaism’s core beliefs is that the land belongs to the divine and she often wondered how humanity could justify mining and other processes that alter the earth.

“To see that sort of rape of the land, to see something just come in and tear up the land … from when I was tiny, I was like, ‘How do we feel like we have a right to do that?’” Siegel said. “The land belongs to the greater, to the divine, however, you want to define that … and so you have no right to alter it fundamentally.”

Abrahamic religions view humans as “stewards,” who have a unique responsibility to care for the planet. The creation stories in Genesis call upon humans to be stewards of creation and tenders of the garden.

Shqeirat talked about what he called the unique responsibility and burden humans have to maintain the Earth.

People “have the ability and the skills to lead and to fix (the world), to maintain it, or to destroy it. And God commanded us to set a good example,” Shqeirat said. People “are in charge and responsible because we have the free will to do good or to do bad.”

Other faith traditions, like Buddhism, Hinduism and many Indigenous traditions, believe that while people still need to take care of the planet, they don’t possess a unique responsibility, but are just one part of the larger ecosystem.

Vasu Bandhu, who practices Zen Buddhism, emphasized the importance of interconnectedness in Buddhism and said Buddhists believe all beings are equal.

“We think in terms of interconnectedness,” he said. “It means that we have dignity, all the beings, not just the human beings. You can find in some Buddhist communities that we pray for other beings. We pray, for example, the doggies or kitties that have passed away. So we pray for them, because we believe that we are equal of the beings.”

A deeper connection

In Hinduism, many gods take the form of animals. Seeing the divine in animals allows for a deeper connection to the natural world, according to Soumya Parthasarathy, a systems analyst.

“Whenever you see an elephant, you think of Ganesha,” she said, speaking of an important god in Hinduism, who possesses an elephant head. “From a young age, I have developed this connection about all the animals as a form of God. So that's how I think I have a deeper connection to care for the environment.”

Parthasarathy also spoke of several mantras, or prayers, that encourage worshippers to be mindful and show appreciation of the natural world.

“As soon as we wake up, before touching the ground we say … 'Earth, you’re my mother but then I'm going to be walking on you. So I'm sorry for that, but thank you,'” Parthasarathy said. “When I say those words, there is an emotion that builds inside. It's a reminder for myself that I have to take care of the planet.”

Another example is surya namaskara, or the sun salutation, a vinyasa flow performed during yoga.

“It has 12 asanas, 12 poses, and every pose has a one-line mantra for appreciating the sun,” she said. “So you are my friend, you are my brother, you are the one who brings light on the planet.”

Bandhu said he considers cooking a form of meditation because he reflects upon all the processes necessary to create food.

We “appreciate the food that we have and how everything that happened around the environment need to happen in equanimity so we can be alive,” he said. “You can find in my specific tradition, that we meditate while cooking. That means that we appreciate the food as a result the movement of the environment.”

Parthasarathy said that reincarnation, a key concept in Hinduism that says humans and other beings are reborn, is a key driver for her to compost.

A banana peel might become food for earthworms and other creatures. And when those creatures are able to sustain themselves, they will reproduce.

“But I don't know what I'll be next in my life. I don't have that concept. But what I know is the environment,” she said. “If I bring it back to sustainability, we have cradle to cradle cycle of resources … It's the recycling symbol. That's basically the reincarnation for me.”

Given the importance of rebirth, she has tried to make several Indian and Hindu festivals, zero waste, including the festivals of Diwali and Navaratri.

The rights of plants and animals

Bland and his wife accompanied the Akimel O’odham tribe when they made the trip to Organ Pipe National Monument and harvested saguaro.

After they pull the fruit from the tree, the tribe crushes the fruit and makes wine out of it. Afterward, they perform a ceremony, called "singing down the rain," which the tribe hopes will usher in rain.

“They have said that the saguaro is not just a plant, it’s kin. And it should have the rights that human beings have,” Bland said. “And the legal system we have now has people and then it's got property. If you're not people, you’re property. And you can do with property whatever you want. But there are some in our religious traditions who say that rivers should have rights and air should have rights and saguaros should have rights. And not just people.”

He said the United Church of Christ recently devised a resolution saying nature should have rights as well as human beings.

“I think it's an idea that we've mostly forgotten,” Bland said. “But Indigenous people now are trying to teach us again about what is sacred. We've become so materialistic in our thinking, that the only thing that is sacred is money.”

Other religions recognize specific rights reserved for animals.

The Qur’an prohibits hunting for sport. Muslims believe that animals and the planet will testify for or against them on the day of judgment.

“The absolute 100% decision with no distinction in the Qur’an is justice,” Shqeirat said. “At least two verses say that very, very clear. This justice is to be towards other humans, towards other creatures.

In one hadith, Prophet Muhammad is recorded to have admonished two men who stole chicks from a red sparrow. As the sparrow flapped her wings, the Prophet said, "Who has devastated this (bird) by taking her children? Return her children to her."

And in Judaism, kosher laws intend to protect the future of a species.

“In the kosher laws, one of the reasons that milk and meat are not eaten together is because you don't bathe the baby in the blood of its mother,” Siegel said. “You would not cook beef and milk together, because that's the mother and the baby, you are potentially eating both, and that is destructive to the future of a species.”

A responsibility to future generations

Siegel described how “l'dor v’dor,” which means from generation to generation, is a common and revered expression in Judaism.

“Everything that we do — the idea of planting trees — everything that you do in your life is supposed to be for your children's children. You should be thinking at least those two generations,” she said. “It's a driving cultural value. I don't see that it gets applied as consistently to the idea that we need a world for our children, but it is certainly a way to engage, our older generation, that they have the responsibility to make their sure there is a world for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

She mentioned the Jewish ideal of "tikkun olam," which means healing the world.

“I think that the most powerful message isn’t a long message,” she said. “It’s the idea that we have the capacity to heal our world. We have been given the intellectual gifts, whatever the cognitive capacity to make a difference. And it's our responsibility to do that for future generations.”

Tikkun olam encourages positive action and says not to be “paralyzed by despair.”

“To see a need and not address it is the language that comes up over and over as the worst kind of action,” she said. “It's one thing if you don't know, but if you know, and you choose to not change, that is complicit.”

Zayna Syed is an environmental reporter for The Arizona Republic/azcentral. Follow her reporting on Twitter at @zaynasyed_ and send tips or other information about stories to zayna.syed@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: People of faith seek a deeper connection to the environment