Amid huge demand for STEM workers, a retired professor helps students from India navigate the visa system

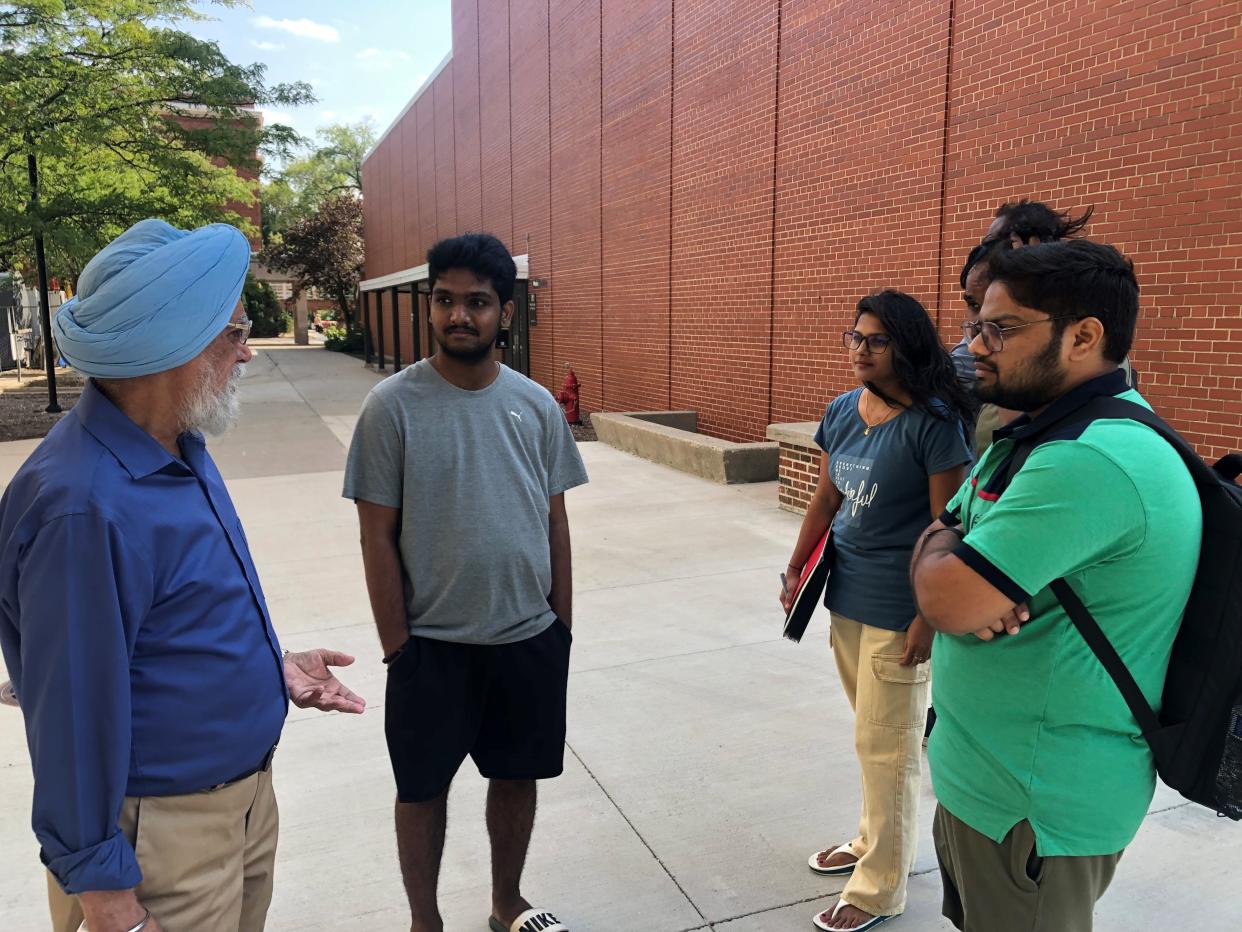

On a sunny day about a week before fall classes began at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, retired economics professor Swarnjit Arora was out for a stroll on campus when he encountered a half-dozen newly arrived students from India.

The students, about to start master’s programs in data science, software development and engineering, were marking their first days in the United States with photos in front of a fountain. Arora was happy to make conversation.

Had they found a nice place to stay? What are they studying, and did anyone get financial aid or scholarships? Be sure to get involved in the Students of India Association, which hosts celebrations for Diwali and Holi, and gatherings throughout the year, he said. And, Arora said, the group provides helpful information on finding internships and securing work visas after graduation.

“So good to see you guys,” Arora told the students cheerfully. “Have a wonderful time.”

To Arora, who taught for 46 years at UW-Milwaukee and is himself an Indian immigrant, the interaction was familiar. He has watched thousands of international students pass through, and has been adviser to the Students of India Association for four decades and counting.

He knows well the challenges international students face in the U.S. — from pressure to succeed to financial strain. He’s especially concerned with how difficult it has become for students trained in crucial fields like technology and engineering to secure work visas to stay in the country long-term.

“It used to be very easy,” Arora said. “But it’s getting harder.”

More: They grew up legally in Wisconsin. Green card backlogs mean they may have to leave the U.S.

Immigrants are a key ingredient in the U.S. competing globally in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). More than half of all master's-level STEM students in the U.S. are from another country, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service.

But caps on H-1B work visas, which allow U.S. employers to employ foreign workers in specialty occupations, are considered too low by many. Further, there are huge green card backlogs for people from countries that contribute the most STEM workers, one of which is India.

Every year, 300,000 to 400,000 people apply for a pool of only 85,000 work visas. Meanwhile, there are more STEM jobs than skilled American workers can fill, and international students are eager to stay here and work, said Grant Sovern, a partner at Quarles & Brady who leads its immigration practice.

“I see many, many Wisconsin companies who you would (think), ‘Why are they hiring a foreign student? Can’t they hire somebody here?’ But they can’t,” Sovern said. “They are literally desperate to hire people.”

Further, research shows new immigrants are necessary if metro Milwaukee is to grow and thrive.

More: UW System enrollment holds steady, with most universities reporting modest declines

International students must navigate murky immigration system

Indian students and their families often view an American degree as a good investment, Arora said. Parents are willing to pay the higher international student tuition, which usually doesn’t come with financial aid, banking on the hope their children will land high-paying jobs in the U.S.

But staying long-term is neither easy nor guaranteed.

Students with STEM degrees can work in the U.S. for up to three years after they graduate, under a program called Optional Practical Training. Each year they can enter the H-1B work visa lottery, which randomly selects 20% to 30% of applicants.

People who don’t win in any of the three years must return home — or go back to school for another degree.

“They all come with dreams,” Arora said. “But if the dream doesn't come true, then they’re in difficult shape.”

Arora helps students navigate the system, and find jobs and training.

He also assists with more personal matters. If students don’t have a place to live, or are homesick, Arora and his wife welcome them into their home.

If students want to go to a Sikh or Hindu temple in the area, he’ll arrange a ride or drive them himself. He encourages them to mingle with non-Indians in the student union to avoid isolation, and he meets their parents when they visit.

“If I can help them, why not?” Arora said.

Professor finds joy in paying it forward

At age 83, he knows what it’s like to scrabble and work hard to succeed. When he was 7 years old, the violent partition of India forced his family to flee current-day Lahore, Pakistan. As a child in Indian refugee camps, he read books and completed homework at night under streetlights.

In college, a professor helped him secure a position in a doctoral program in Buffalo. Because India didn’t allow international currency exchange, he arrived in 1967 with $3.54 in his pocket.

UWM recruited Arora — trained as a mathematician — to join the economics department in 1972.

Arora expresses deep gratitude for the professors and administrators who helped him and made him feel welcome through his career.

“I have been very blessed,” he said. “I had no money. I didn’t know anything.”

"It’s been a joy to pay it forward to the next generations."

This project is supported by a grant from Marquette University Law School's Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education, to make possible journalism on issues of importance to the Milwaukee area. All the work was done under the guidance of Journal Sentinel editors.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: With STEM worker demand, professor helps students navigate visa system