‘Amplifying the voices of those muted by history’: Challenges of researching Black history

“Black history is American history,” actor Morgan Freeman said in a 2005 “60 Minutes” interview. They are not really separate.

But there are extra challenges in researching historical events of marginalized populations, where records are more difficult to acquire or were never there at all. We have journals and letters from frontier explorers, but what do we have for the Native Americans from the same period? We have reams of legal records, correspondence and newspapers covering Cincinnati in the 19th century – what do we have for the African Americans living here at the time?

Mining historical resources to tell stories of those marginalized, ignored

Nikki M. Taylor, a history professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C., has written three books on African American history in Cincinnati, including “Frontiers of Freedom: Cincinnati’s Black Community, 1802-1868” and books on educator Peter H. Clark and the fugitive slave Margaret Garner.

Our history: Peter H. Clark educated generation of city’s black teachers

Our history: Margaret Garner’s story has resonated for the past 164 years

“The period I write about is a time when city leaders, officials, politicians, citizens and historical records gatekeepers did not value their perspective or voices, so they did not record the things they said or preserve their documents,” Taylor wrote in an email response to questions about the challenges of researching Black history.

“Although there are a few exceptions, for the most part, the lives, political views, accomplishments, thoughts, intellect, and cultural practices of the masses of everyday African Americans were not deemed valuable.

“So historians like me, who are committed to African American history, must seek to find them in the sources left by whites. Some of the sources are dripping with vile racism and white supremacy, which was difficult for me to stomach.”

Taylor gave an example of mining the records of the American Colonization Society that concluded that African Americans should be sent back to Africa. In those records she found that Charles McMicken, who had bequeathed money and property to found the University of Cincinnati, where Taylor worked at the time, had also funded a project, “Ohio in Africa,” that was a deportation society.

“But it is from those same records that I learned that a small group of free African Americans in Cincinnati made plans to leave the country for good on their own terms and go to Liberia,” Taylor wrote. “They were tired of the obstacles and just wanted to find a place where they could have peace and be free of white racism. This is the start of what we now call black nationalism in the city which amounted to a desire for ‘self-determination’ and ‘independence’ back then.”

The scarcity of resource material can hamper research. Slaves were often prohibited from getting an education. They rarely wrote journals or letters, weren’t in the census and seldom had legal documents.

“There are primary sources for almost anything in U.S. history. It takes a commitment to doing that history that matters,” Taylor wrote. “The sources you find may not all be from the black perspective, though, so you have to ‘read against the grain’ the sources you do have. For example, if all you have are slaveowners’ journals and no diaries written by African Americans, then you cannot just throw up your hands and say a book on African Americans in slavery cannot be written because they did not leave primary sources. Much info can be gleaned from the slaveowner’s journal or other sources.”

Such resources include the Freedmen’s Bureau (for assisting those freed from slavery), wills and probate records of slaveowners (because slaves were listed as property), slave schedules for the 1850 and 1860 censuses, plantation records and church records. Compounding the issue are errors in spelling and dates, as well as people lying about birth dates, ethnicity or education.

Taylor also wrote of her struggles to access research materials. “The archivists that lord over these records are not as helpful as they could be to black scholars,” she wrote, describing archivists who watched her carefully, were slow to bring materials or pretended not to have certain records. She eventually befriended a white scholar who retrieved the files for her.

“This is what black historians go through,” she wrote. “It is exhausting and very real. I remain committed to amplifying the voices of those muted by history.”

Our history: Black photographer J.P. Ball was pioneer in Cincinnati, exposed ills of slavery

Our history: Book a trove of city’s African American history

Giving voice to African Americans

Slave narratives were popular in the 1830s to 1860s and were often used as tools by abolitionists to expose the harsh realities of slavery. Pro-slavery advocates tried to poke holes in the facts of the narrative, but historians believe that most of the slave narratives were authentic, yet copyedited and corrected for grammar by abolitionists.

The autobiography of John P. Parker is a striking local example. Parker was born into slavery in Norfolk, Virginia, but earned money to buy his freedom, and settled in Ripley, Ohio, about 50 miles upriver from Cincinnati in Brown County. There he owned his own iron foundry and secretly worked as an extractor on the Underground Railroad.

Assisting the escape of slaves was illegal and dangerous, due to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, so Underground Railroad conductors left few records.

Reporter Frank Moody Gregg interviewed Parker in the 1880s, recognizing a rare opportunity to record the African American experience in the Underground Railroad. The manuscript was left unpublished in the Duke University archives for more than a century, then was edited by Stuart Seely Sprague and finally published as “His Promised Land” in 1996.

By comparing the Parker manuscript with another that Gregg wrote based on the interviews, Sprague concluded that the Parker version has a roughness and tiny details that are “close to Parker’s voice.”

“How I hated slavery as it fettered me, and beat me, and baffled me in my desires,” Parker said. “… It was not the physical part of slavery that made it cruel and degrading, it was the taking away from a human being the initiative, of thinking, of doing his own ways.”

Such historical finds are rare. About 200 slave narratives have been published in total. But, if there are few records of the African American experience, how are we to learn about it?

Jinny Powers Berten, a Cincinnati author who has volunteered at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center for 17 years, faced that problem when writing “By His Side: The Story of George Washington and William Lee,” a historical fiction about Washington and his enslaved valet.

“There are no primary sources at Mount Vernon for William Lee,” Berten said in an interview. “There’s a ton of sources, of course, for Washington, nothing for William Lee. … Because the people of the time did not think slaves were of enough value to write down about them. …

“I feel very strongly that those people need a voice. And if you don’t give them a voice, it’s silent. In that case, I had to create the dialogue. So it’s fiction. Now, Washington’s death scene was recorded … so I could get all that, even some of the dialogue.”

Because the book is historical fiction, some museums won’t take it, Berten said. Yet, it is in the tradition of other books that have given voice to African Americans, like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.”

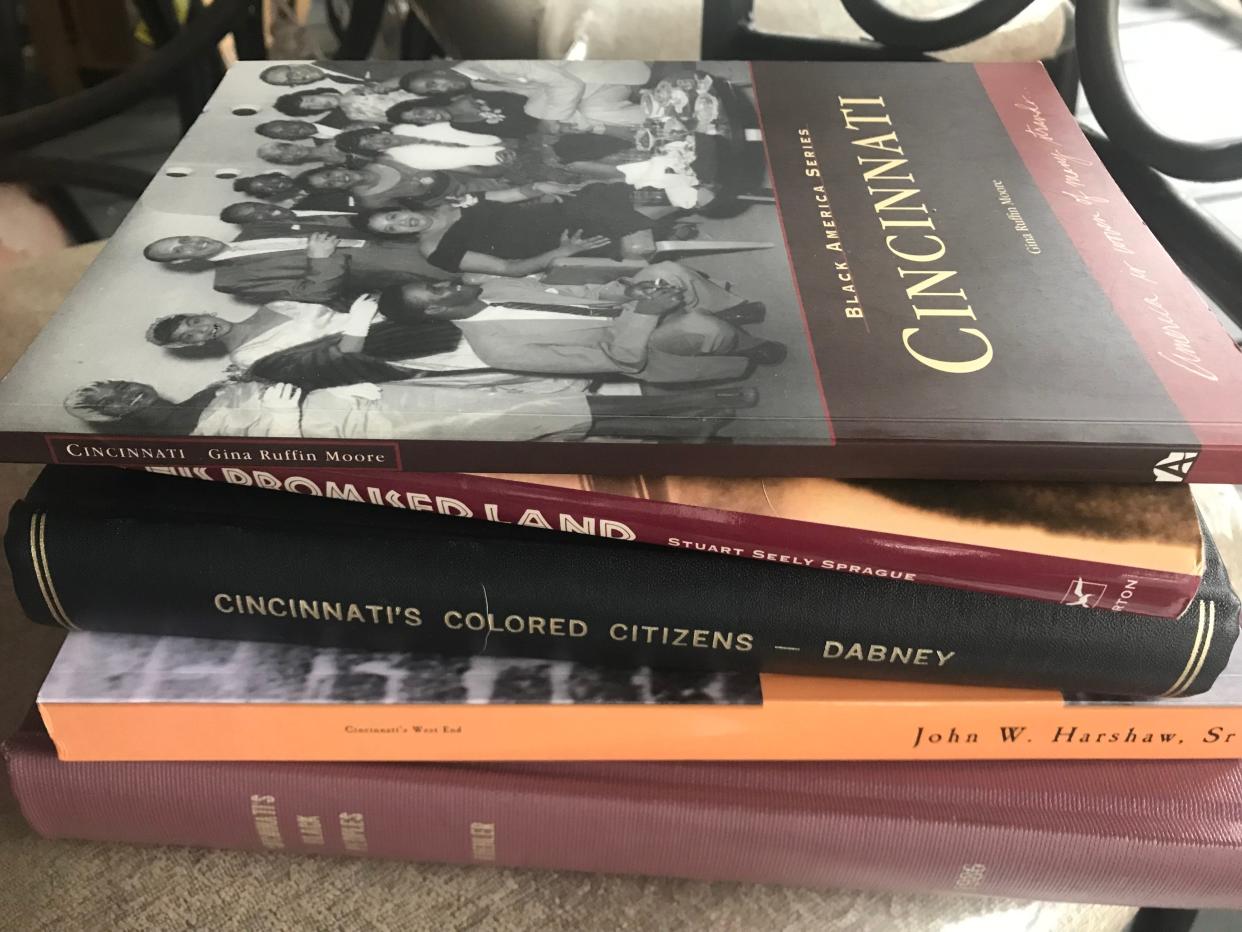

Other resources about Black history in Cincinnati

“Cincinnati: Black America Series” by Gina Ruffin Moore

“Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens” by W.P. Dabney

“Cincinnati’s Black Peoples” by Lyle Koehler

“Across the Color Line: Reporting 25 Years in Black Cincinnati” by Mark Curnutte

“The Black Brigade of Cincinnati” by Peter H. Clark

“Cincinnati’s West End” by John W. Harshaw Sr.

Guide to African American Resources (library.cincymuseum.org/aag/guide.html)

The Voice of Black Cincinnati (thevoiceofblackcincinnati.com)

“West End Stories Project” podcast

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: A gap in historical records: Challenges of researching Black history