Analysis: Censorship movement in Pennsylvania looks much like the battle over Superman

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In February 1955, a Girl Scout troop in Indiana, Pennsylvania, kept warm around a “Bonfire for the Future,” a comic book burning.

The ceremony, targeting comics that refused a then-new industry censorship code, displayed the troop’s opposition to “obscene” reading materials threatening to indoctrinate the nation’s youth.

Like more than a dozen other comic book burnings across the country over a decade prior, the smoldering fires were fueled by many things, primarily parental fear and stories about an alleged icon of fascism: Superman.

The comic book industry had been booming through the later years of The Great Depression and into World War II, a cheap form of entertainment and pro-war propaganda.

While stories of Captain America winning fist fights against Adolf Hitler helped drive the popularity of comic books at home and abroad, the visual medium of comics led to a public perception that they were children’s books with no literary or artistic value.

The rise of superhero comics in the late 1930s opened the door for crime and horror comics in the 1940s, prompting scrutiny by teachers and parents over stories of the macabre and the supernatural.

Spurred by anxieties that illustrated dime magazines would turn their children into criminals and sexual deviants, parents and lawmakers pressured a burgeoning comic book industry into self regulation.

More: At risk in Pennsylvania schools - books, political talk, LGBTQ policies

For decades, a set of guidelines made "a positive contribution to contemporary life” by censoring stories that undermined government institutions, disrespected family values or even hinted at “illicit sex relations” threatening the “sanctity of marriage.”

While cultural changes eventually ended the Comics Code Authority of the 1950s and made book burnings and censorship taboo, the moral panic that created them is alive and well in a parental rights movement today that’s sweeping the nation.

Public and school libraries are the new battleground where protecting children from “pornography” or “grooming” by sexual predators usually means restricting books about systemic racism, gender, sexuality and anything that one side considers “woke” political indoctrination.

A library policy passed by the Central Bucks School District, the third largest in Pennsylvania, has become boilerplate policy language considered or adopted in smaller districts across the state.

Readings of classic and contemporary titles tackling systemic racism, sexual assault or LGBTQ issues are read out of context in school board meetings to push restrictive library policies as lawmakers across the country push parental-rights legislation.

Although not the sole focus of this new pro-censorship movement, comic books and long-form graphic novels are often singled out as “subliterate” picture books with no educational value for children.

In the battle for the library, comic books might hold the most valuable lessons for all sides.

Comics bleed history

In 1938, Action Comics released its first issue of a story about the last surviving Kryptonian who fell to Earth and became “a champion of the oppressed … helping those in need!”

Superman started a new genre of superhero comics that have spawned a vast swath of household names through blockbuster films and television shows.

More than a decade after his first issue, however, The Man of Steel was considered the source of one prominent pyschiatrist’s theory on why young boys were turning into criminal brutes.

During a 1954 Senate Subcommittee into Juvenile Delinquency hearing, Dr. Frederic Wertham testified that the violence in Superman comics led to “The Superman Complex,” which explained a rash of violent attacks among male students in a New York State high school.

“(Superman comics) arose in children's fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune … In these comic books the crime is always real, and the Superman's triumph over good is unreal. Moreover, these books, like any other, teach complete contempt of the police,” Wertham told the senators.

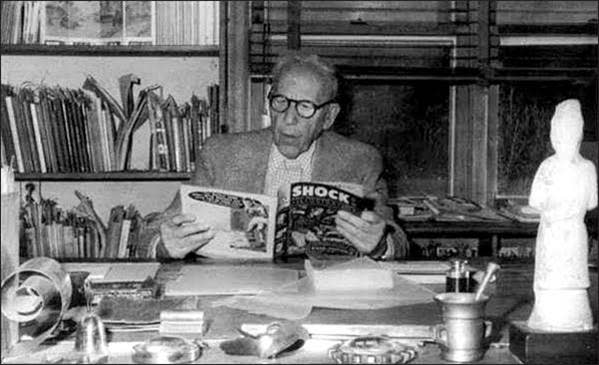

The Senate investigation, which carried with it the threat that the government would censor the comics industry, followed nearly a decade of public demands to ban comics. Included in those protests were horror and crime comics like “Tales from the Crypt,” drawing most of that ire.

Wertham’s testimony, largely taken from his published study “Seduction of the Innocent,” confirmed parents’ fears that ghoulish stories that included torrid love affairs were turning their children into criminals and sexual deviants.

In addition to blaming comics for the violent fights at the unnamed New York school, Wertham said the “ethical and moral confusion” from comics were also responsible for at least 26 teen pregnancies.

The nation’s sons were corrupted by tales of glorified youth while its daughters were being “seduced mentally long before they were seduced physically,” Wertham said.

William Gaines, owner of EC Comics, which published “Tales from the Crypt” and several other series, pushed back.

“We think our children are so evil, simple minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery?” Williams asked at the hearing.

Fearing government censorship, the Comics Magazine Association of America acquiesced to the outrage and formed the Comics Code Authority. Publishers would need to meet broad standards to print the CCA’s seal of approval or be turned away by retailers.

Gaines’ company would eventually fold its horror and crime comics, due to the regulations set by the CCA, including bans on depictions of “the walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism.“

The CCA is why Batman today is portrayed as staunchly against using guns or killing criminals, despite pre-CCA issues showing the orphaned billionaire gunning down Gotham’s criminals.

Any depictions of police or government corruption were also banned by the CCA, as was anything that didn’t “emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.”

Wertham also suggested in “Seduction of the Innocent” that Batman and his sidekick Robin were actually a gay couple, citing various scenes of the two characters at home in Bruce Wayne’s mansion.

“It is like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together. Sometimes they are shown on a couch, Bruce reclining and Dick sitting next to him, jacket off, collar open, and his hand on his friend’s arm,” Wertham wrote.

During his testimony, Wertham more directly laid out the dangers of these “homosexual fantasies” in comic books.

“Nobody would believe that you teach a boy homosexuality without introducing him to it,” Wertham said.

In other words, Wertham argued that comic books could turn children gay. It’s important to note that being in a same-sex relationship was illegal until states slowly began repealing anti-gay laws in 1961.

The Supreme Court didn’t rule anti-sodomy laws as unconstitutional until 2003.

Incremental cultural shifts like the gay rights movement would eventually reshape the CCA over decades, but its restrictions against “illicit sexual relations” would have lingering effects on gay representation in mainstream comics.

Marvel Comics debuted its first gay character, Northstar, in 1979, but the character’s sexuality was left mostly to innuendo and rumors for more than a decade.

By the early 2000s, the CCA became a relic of a bygone era ignored by publishers and comic sellers alike. By the early 2010s, the Comics Magazine Association of America was dissolving and the censorship code along with it.

The rights to the CCA Seal of Approval were transferred in 2011 to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, a nonprofit helping to fund censorship battles against authors, publishers and comic book stores since 1986.

The CBLDF uses the seal now in its fundraising efforts.

Jeff Trexler, executive director of the CBLDF since 2020, said the end of the CCA also raised questions about whether the nonprofit’s days were numbered as well.

Censorship had become a four-letter word to many Americans, book burnings were seen as extremist and comic books were in the midst of a popular culture renaissance.

“Every so often, you get complaints about mainstream books, one here, one there, but it really hadn't hit a critical mass. To the point that by 2020 … there were a lot of people wondering, ’Well, maybe we don't need a Comic Book Legal Defense Fund anymore.’” Trexler recalled.

“That was, I think, a common sentiment just three years ago. And after that … the deluge.”

Public school mitigations for the coronavirus pandemic brought about a new wave of parental rights activism.

Parents were getting a close look into lesson plans through online learning in the early days of the pandemic and voicing their dissatisfaction in school board meetings — many districts posting videos online for the first time due to coronavirus restrictions on public gatherings.

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 prompted protests against police brutality and systemic racism, which in turn led to discussions about how racism was taught in schools.

Those discussions led to fears that “critical race theory,” a college-level legal analysis through the lens of race, was being taught in grade schools.

A common early concern from groups like Moms for Liberty and Parents Defending Education was that the books were teaching children to hate the police, that America is founded on racism and that white people should be demonized.

In early 2021, those groups began to “expose” school libraries allegedly filled with “pornographic” material that would prime them for sexual abuse or make them believe they were transgender.

The American Library Association, which had tracked book banning attempts for 20 years, saw a record breaking 729 challenges in 2021. The following year nearly doubled to 1,269 challenges.

“Of those titles, the vast majority were written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community and people of color,” the ALA reported in March.

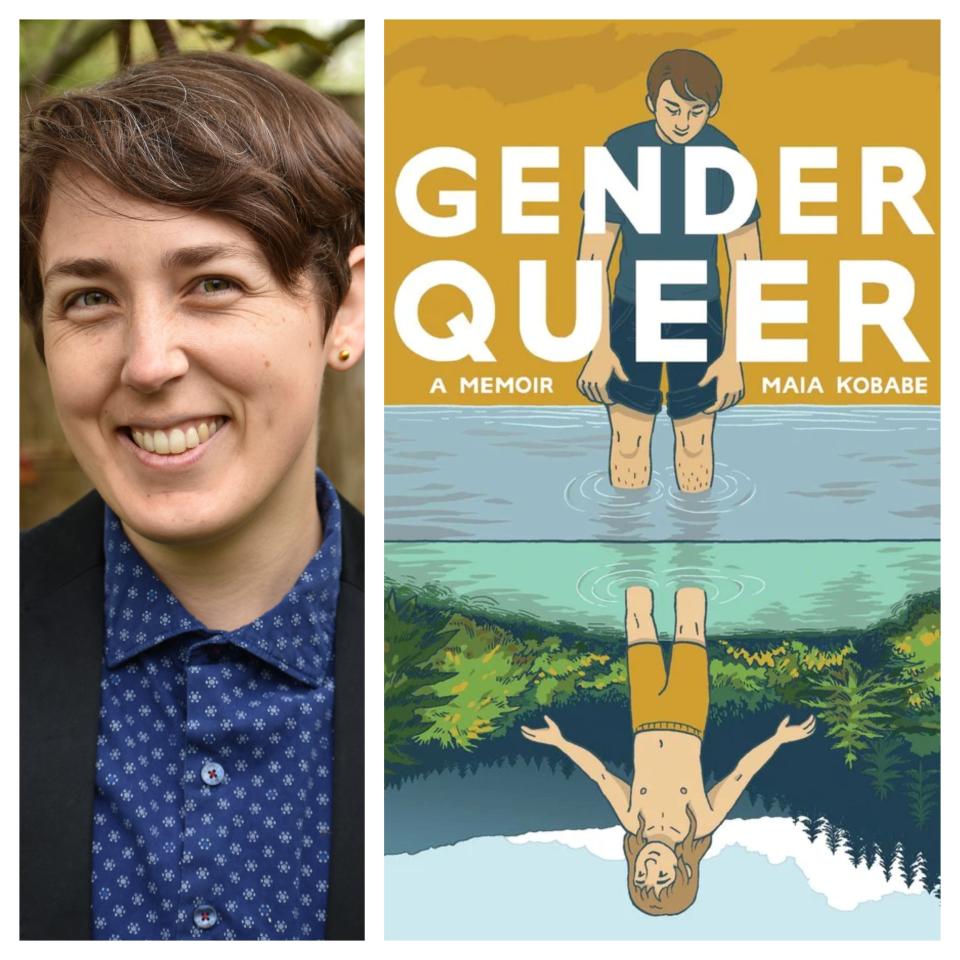

The most challenged book in 2021 and 2022 was an autobiographical graphic novel, “Gender Queer,” following author and illustrator Maia Kobabe’s nonbinary coming-of-age story.

A ban by any other name

For almost two years, supporters of the new censorship movement have called out “Gender Queer” for “pornographic” imagery and rebuked critics’ accusations that they are singling out LGBTQ books.

The visual medium of comic books make them often more accessible for readers, but it also means they are easier to use out of context to rally opposition.

While Kobabe explores the complexities of gender identity, gender-neutral pronouns and sexuality through frank and vibrant illustrations that some might call “necessary representation,” the new censorship movement deems a few frames as “pornographic” and ignores the rest of its 241 pages.

More: Central Bucks School District orders librarians to remove two LGTBQ+ themed books

“This book contains obscene sexual activities and sexual nudity; alternate gender ideologies; and profanity,” reads a description on BookLooks.org. Framed as an objective rating system for library books, BookLooks has become the favored resource among groups such as Moms for Liberty.

While BookLooks website says it is not tied with Moms for Liberty or other organizations, critics and censorship researchers have said the ratings website and largely conservative groups seem to at least work in tandem.

The more than 60 titles that fell under the first wave of challenges in Central Bucks earlier this year were made up of what appeared to be excerpts lifted directly from BookLooks’ summaries.

The website uses a sliding scale from zero to five to determine the age-appropriateness of more than 550 titles, as of early May. About 46% of those books received ratings of three or more, which would restrict them from being accessible to anyone under 18, according to BookLooks.

At first glance, the rating system seems to punish books where sex, drugs and violence are concerned.

Kobabe’s book is rated four, but books that contain “explicit gender ideologies” can be rated a two, meaning “some content may not be appropriate for children under 13.”

Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel “Fun Home,” described by BookLooks as the author’s discovery that she is a lesbian following her father’s suicide, is rated the same as Kobabe’s memoir.

Both feature “alternate gender ideologies” and “sexual nudity” on their BookLooks summaries.

Chuck Palahnuik’s “Fight Club” is rated three on BookLooks, a striking ruling considering the contents described within.

“This book contains sexual activities; references to aberrant sexual activities; sexual nudity; violence; references to abortion and suicide; alcohol use; and profanity,” according to BookLooks.

Titles rated a five on the website — BookLooks' worst of the worst material — gain the rating for having “aberrant” content, but a book that champions hypermasculinity apparently gets a pass.

The five-page inventory of questionable content for “Fight Club,” which is 10 pages less than Kobabe’s book received, also doesn’t include multiple instructions for homemade explosives in Palahnuik’s book.

Just like in the CCA of the 1950s, the new censorship movement is less about analyzing the context of literature and more about promoting a certain group’s values.

Lessons of a Red Son

Whether traditional prose or drawn frames on a page, literature helps us understand ourselves through close, analytical reading. Even an undermined medium like comic books offers value to readers of all ages, often through challenging our own beliefs.

To that point, consider Mark Millar’s 2003 “Superman: Red Son,” a three-issue re-telling of the story of Kal-El, who crashed to Earth in Ukraine instead of Kansas.

Used by the Soviet Union as the superiority of the proletariat, Superman soon vows to lead his countrymen to prosperity after seeing the horrid living conditions of his childhood friends. While battling a hot and cold war with American Lex Luthor, the superhuman hero spreads his utopia across the globe as nations fear retaliation from behind a literal iron curtain.

Over decades, the fight between Superman and the West raged on as Luthor employs allies and villains familiar to fans of the series. Luthor teamed up with the alien Brainiac, a villain who was known for shrinking the capital city of Krypton in mainstream Superman comics. As part of Luthor’s plot to undermine Superman’s authority and power, he and Brainiac plot to shrink Moscow but accidentally shrink Stalingrad.

While Superman is able to defeat and forcibly convert Brainiac to his cause, the Russian metropolis and its residents are permanently left miniaturized and under glass in Superman’s Fortress of Solitude. Luthor’s weapons and plots fail to stop Superman’s plan to bring the world under his rule. After Luthor is eventually captured, Superman’s armies descend on the White House in a final climactic battle.

The last blow that ultimately leads to Superman dismantling his army and leaving Earth for humanity to find its own destiny comes from a note Luthor left before his capture and delivered by First Lady Lois Luthor. A single question: Why don’t you just put the whole world in a bottle, Superman?

With the realization that his conquest was about domination instead of liberty, Superman leaves Earth to let humanity find its own destiny.

Millar’s series presents two lessons aptly applied to the new censorship movement.

The first is a moral lesson: Forcing the world to bend to one individual’s ideals means robbing others of their agency, even in the name of protecting those important to us.

The second is a simple reminder: To fascists, words are the most dangerous weapon.

This article originally appeared on Bucks County Courier Times: Analysis: The movement that once burned Superman comics has returned