Analysis: Texas police officers frequently acquitted even after social justice movement

One year ago, Texas juries delivered different verdicts when they judged two controversial fatal police shootings.

A Fort Worth jury convicted officer Aaron Dean on a manslaughter charge for shooting and killing 28-year-old Atatiana Jefferson through a window of her mother’s home in 2019 after responding to a call for a wellness check. He received a nearly 12-year prison sentence.

Three months earlier, a Hunt County jury acquitted Wolfe City officer Shaun Lucas in the October 2020 shooting of 31-year-old Jonathan Price. Lucas had responded to reports of a fight outside a store and said Price tried to grab his Taser. Prosecutors, who charged Lucas with murder, argued Price was extending his hand.

Among officers statewide who have stood trial for on-duty lethal shootings, the outcome Lucas received is more common than Dean’s.

In a new era of police accountability in Texas and across the nation, a wave of prosecutions of police officers has sparked headlines and generated applause from reformers who view them as tangible advocacy results. But an American-Statesman analysis of seven high-profile cases — identified by police unions and activist groups and most of which went to trial after the 2020 social justice movement — found frequent acquittals when the cases reached a courtroom.

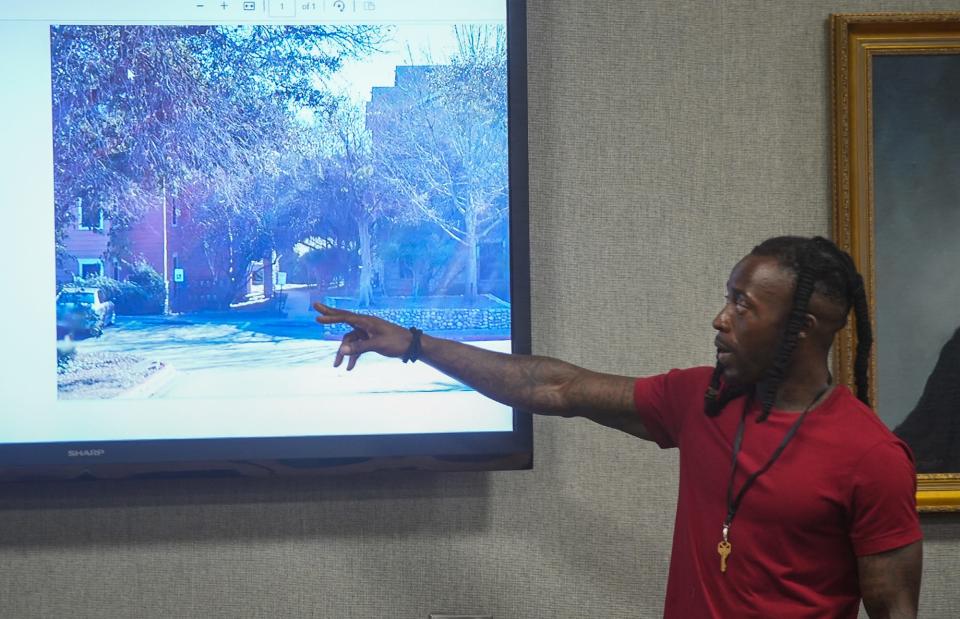

A Travis County jury leaned toward acquittal, but ultimately deadlocked in an 8-4 vote, last week in the murder trial of Austin police officer Christopher Taylor in the shooting death of Michael Ramos, a 42-year-old Black and Hispanic man whose death helped fuel Austin’s Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020. Prosecutors argued that Taylor’s use of force was not reasonable and that Ramos was only attempting to flee when he started driving a Toyota Prius from a parking lot. Taylor’s lawyers contend Taylor feared for his life and the life of fellow officers when he shot.

More: Mistrial declared in murder trial of Austin officer Christopher Taylor in death of Michael Ramos

Taylor and officer Karl Krycia also face a murder charge in the 2019 shooting of Mauris Desilva, who was suffering a mental break when the officers said they shot because Desilva moved toward them with a knife. Trial dates are set for early 2024.

From rural to urban jurisdictions and among Republican and Democratic prosecutors, district attorneys have more frequently brought cases against officers through a trend that started nationally after the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown by officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Mo., and intensified after the 2020 George Floyd murder in Minneapolis.

Still, such prosecutions are rare. A database compiled by The Washington Post shows about 80 Texans have died in police custody since 2018, although not all involved shootings. It also is not clear how many could be considered potentially unlawful. No group or organization tracks how many resulted in criminal charges against officers, but organizations that monitor such issues said they know of no other trials of officers for on-duty fatal shootings beyond the seven the Statesman reviewed.

Other cases pending against Texas officers are not limited to fatal uses of lethal force. Multiple officers have been indicted on charges such as aggravated assault with a deadly weapon amid other excessive force allegations. In Austin, prosecutors have brought indictments against about two dozen officers in the past three years, most of which involved injuries to protesters during the 2020 demonstrations and are set for trial in 2024.

“With the police reform conversation, we have a lot of prosecutors, especially in our more metropolitan areas, that have decided politically it makes more sense to indict the officers, or take them in front of grand juries, and let the grand jury or a jury make that decision,” said Kevin Lawrence, executive director of the Texas Municipal Police Association, which advocates for police.

More: Austin leaders react to mistrial of Austin police officer Christopher Taylor in 2020 shooting

Challenges in prosecuting police

Cases against officers, particularly those involving lethal force resulting in murder or manslaughter charges, still face barriers unique to police prosecutions once they get to the courtroom, experts say.

As in Taylor’s case, circumstances in which officers fired their weapons generally give rise to self-defense claims that can make allegations of a crime less convincing to jurors. Officers might be able to convince jurors that they feared for their safety or the safety of others when a suspect reached into his pocket or turned a certain way, for instance.

“They will often make that claim. Sometimes it is a viable claim, and sometimes it is people on the jury or a judge not wanting to put themselves inside the shoes of an officer and assuming they are credible even if they shouldn’t,” said Kate Levine, a law professor at New York's Cardozo School of Law who has studied prosecutions of police.

Jennifer Laurin, a University of Texas law professor, said once a defendant officer introduces self-defense, state law requires the prosecution to blunt those claims.

“Not only is the prosecution shouldering the burden of proving the elements of the homicide crime that is charged, but also is shouldering the burden of negating the assertion that it was formed in response to a reasonable belief that deadly force was coming against the defendant,” she said.

More: What Austin police officers said in testimony during Christopher Taylor's murder trial

Another reality of prosecuting police is that key witnesses in the case, including those at the scene and those who did the investigation, are fellow police officers. Sometimes, they might be reluctant to testify adversely against colleagues, Levin, Laurin and Texas Tech University law professor Patrick Metze agreed.

"They may say something detrimental to their buddy,” Metze said. “The pressure is on them to protect their own but to tell the truth. It is a difficult call."

Laurin added that officers also are “professional witnesses,” trained in “how to appear credible, in how to give truthful but limited or strategic answers to questions that are being asked of them, and typically, in these cases, witnesses who are not law enforcement witnesses are not professional witnesses.”

And Levine added that many officers can be “better resourced defendants” whose cases are backed by attorney teams paid for by unions.

Juror sentiment toward officers has traditionally been viewed as an obstacle toward prosecutions, with experts believing that officers receive special consideration in the minds of those judging their actions.

Many jurors have not had bad experiences with police officers, Laurin and Levine said, and might be deferential to the work police do in their communities. However, both said it is difficult to determine, without more cases going to trial, if juror sentiment has shifted.

"It is hard to imagine that anyone living in America today is not more informed about the complicated and nuanced role police play in our society than maybe they were 10 years ago,” Levine said.

Case studies

In 2018, a Dallas County jury convicted Balch Springs officer Roy Oliver on a murder charge for shooting and killing 15-year-old Jordan Edwards. Oliver fired into a moving vehicle that he said he thought was about to strike his partner. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Among six other cases that went to trial after 2020 after social justice protests played out nationally, all but Dean’s resulted in an acquittal, although a jury in Burnet deadlocked on one of two charges an officer faced.

Four months before Aaron Dean's conviction, a Tarrant County jury viewed a lethal police shooting differently, acquitting former Arlington police officer Ravinder Singh on a criminally negligent homicide charge in the 2019 death of a woman while he was attempting to shoot a dog.

A spokeswoman for the Tarrant County district attorney’s office did not return phone calls or emails seeking comment about the cases.

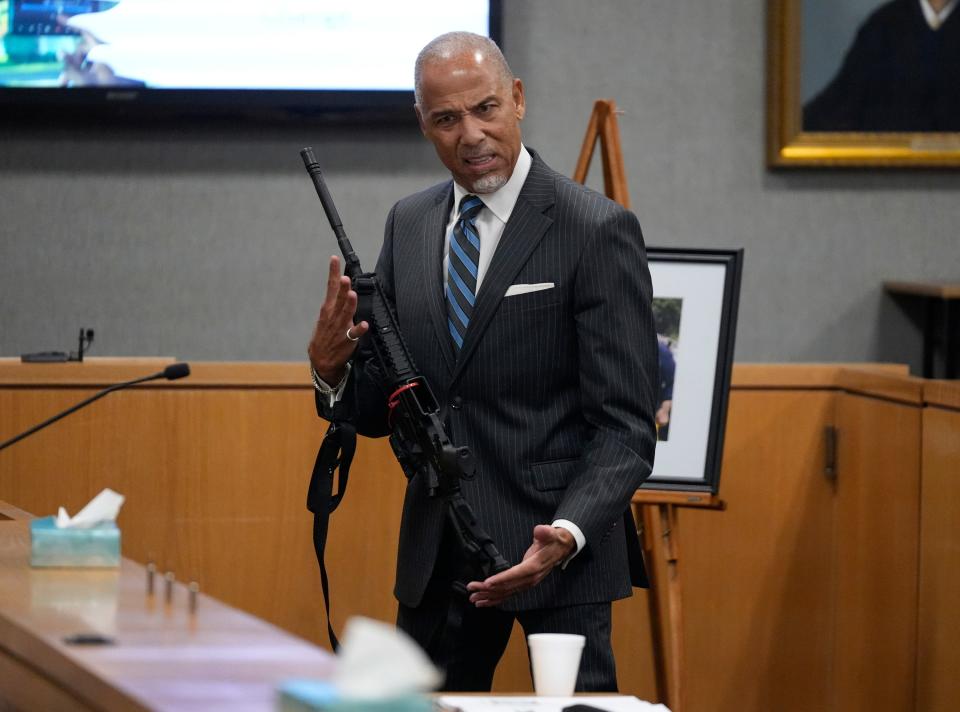

In other urban Texas counties, a Harris County jury acquitted Baytown police officer Juan Delacruz in October 2022 on a charge of aggravated assault by a public servant in the shooting death of Pamela Turner, whom he was trying to arrest on outstanding warrants three years earlier. Delacruz fatally shot Turner, who family members say suffered from mental illness, after she grabbed his Taser and stunned him in the groin.

Prosecutors in more rural areas also have brought cases against police officers that mostly resulted in acquittals.

In August 2022, a Burnet County jury found former city of Burnet police officer Russell Butler not guilty of murder and deadlocked on a manslaughter charge. District Attorney Sonny McAfee, a Republican, told the Statesman recently that prosecutors plan to retry Butler on the manslaughter charge. No date is set. Butler shot and killed 25-year-old Brandon Michael Jacque in 2019 after he said Jacque backed up his car, hitting his foot.

In February, in Bell County, north of Austin, a jury acquitted Temple police officer Carmen DeCruz on manslaughter charges in the death of Michael Dean. The shooting happened when DeCruz, with his finger on the trigger of his gun, shot Dean in the head as he reached to turn off the ignition of his car. DeCruz’s attorneys argued Dean struck the gun with his own hands.

Other Texas trials against police officers in shooting deaths are on the horizon.

During Christopher Taylor's trial, the head of the civil rights division from the Bexar County district attorney’s office attended portions of the proceeding to help prepare to take a handful of officers in Bexar County to trial on charges arising from fatal shootings.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Prosecution of Texas police officers rarely lead to convictions