Ancient Egyptian women wore lower back tattoos for childbirth ‘magic’

Ancient Egyptian women wore ornate back tattoos to protect them during and after childbirth, a new study suggests.

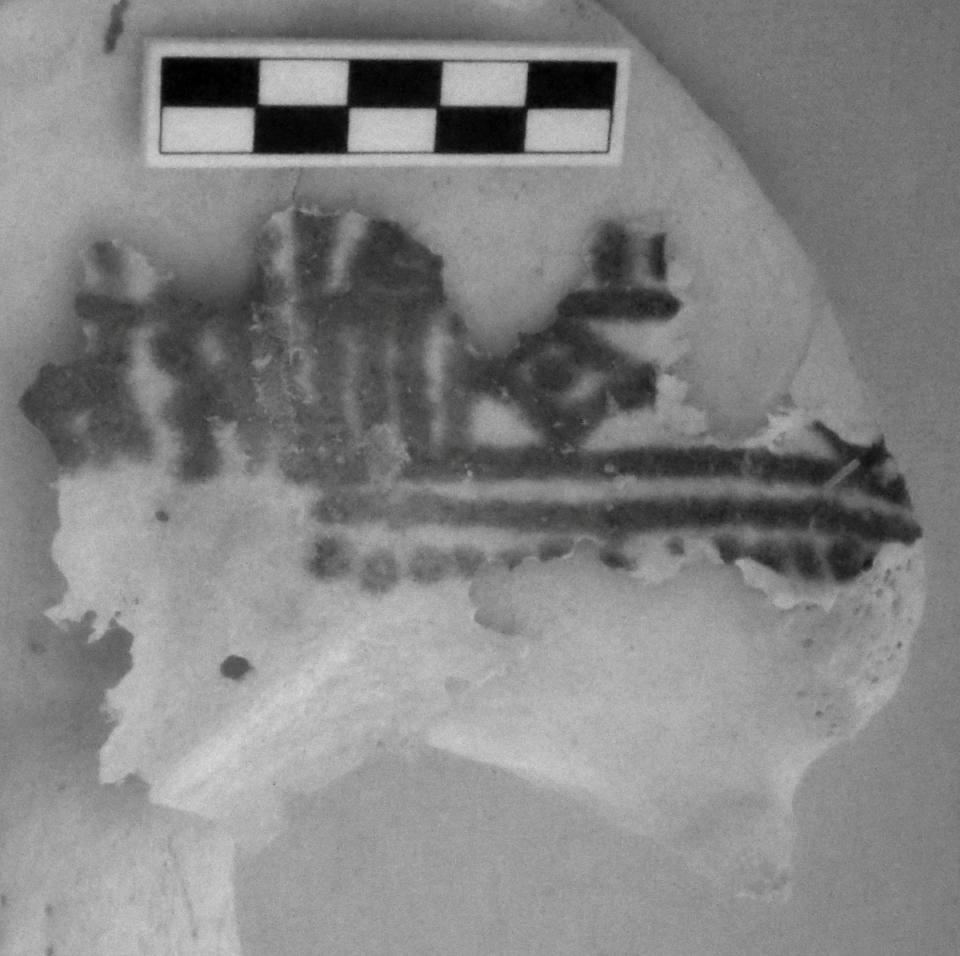

The hypothesis follows examination of mummified remains of two women with tattoo motifs from Deir el-Medina, a site located on the west bank of the Nile, across the river from modern-day Luxor.

This was an ancient Egyptian workmen’s village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Study authors Anne Austin, University of Missouri at Saint Louis, and Marie-Lys Arnette, Johns Hopkins University, suggest a link between the lower back tattoos and figurines with tattoo motifs from Deir el-Medina.

Childbirth throughout history was highly dangerous and one thought is that the birth mother and surrounding midwives may have worn tattoos to elicit “sympathetic magic.”

The Egyptian Goddess Hathor, linked to fertility and a protector of women, has been linked to childbirth rituals.

Egyptian women squatted on bricks while giving birth, and the only known surviving birth brick from ancient Egypt is decorated with an image of a woman holding her child flanked by images of Hathor.

The study, published in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, says: “New evidence of tattoos in human remains in comparison with tattoo-like marks on female figurines shows that these markings connected with the spheres of childbirth and fecundity more broadly.

“Why do these motifs only appear on some bodies and objects, while being ignored on others?

“One possibility is that these motifs were not worn by all women, but only by those who would be involved in the birth-giving process, being midwives and/or women partaking in rituals related to childbirth.

“The hypothesis is supported by the fact that previous tattoos found at Deir el-Medina were linked with Hathor, that is to say, that these women might have been related to the cult of the goddess, and/or with Hathoric rituals in general.

“In this case, the tattoos would be made effective during childbirth by sympathetic magic, the body of the woman in labour being paralleled with the tattooed bodies of the women surrounding and helping her.

“One can also imagine that the figurines showing representations of tattoos would be especially linked with childbirth, that is to say, they would have been used during the event – for example, thanks to their small size, the figurines could have been held in hand by the woman in labour, or by the midwives when performing rituals.

So-called ‘tramp stamps’, tattoos on the lower back, became popular in the first decade of the 21st century, with celebrities including Britney Spears sporting various designs.

A 2011 study of media stereotypes criticised media portrayals of the tattoos, arguing that they were unfairly cast as a symbol of promiscuity.