Ancient Hopewell artifacts linked to historic American Indian traditions | Archaeology

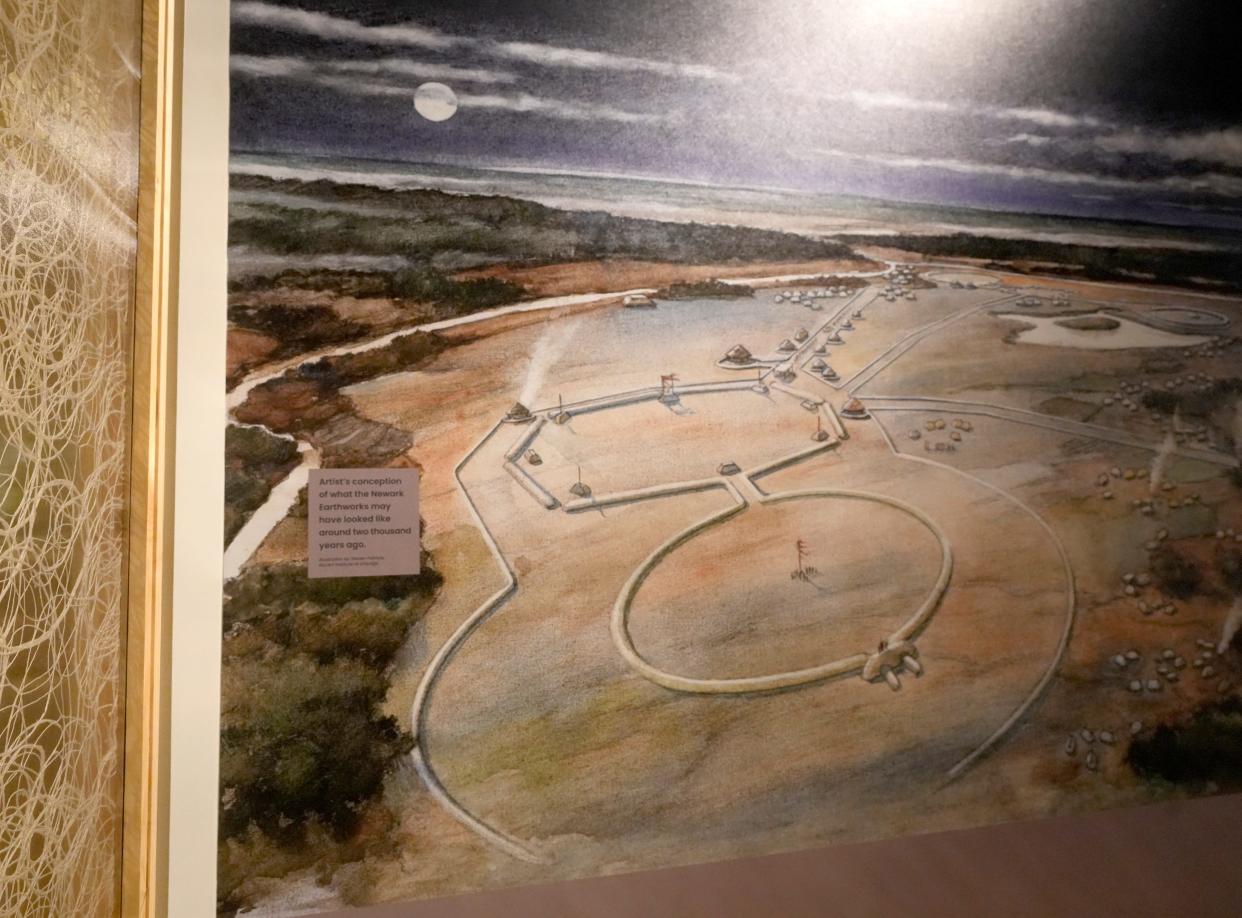

The heartland of the ancient Hopewell culture was in southern Ohio. It was here, 2,000 years ago, in what are now Chillicothe, Newark and other places, where these indigenous people built their largest earthen cathedrals.

It was also here where they created iconic ceremonial regalia from special raw materials brought from the ends of their world.

These artistic masterpieces hold clues to the traditions of the people who built and worshipped at the Hopewell earthworks, but unless some Hopewell equivalent to the Dead Sea Scrolls is someday discovered, how can archaeologists hope to recover those stories?

Ohio's Hopewell mounds:Hopewell earthworks aims for World Heritage list

Speaking at the 1929 Annual Meeting of the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (now the Ohio History Connection), Henry Roe Cloud, a Winnebago tribal member, wondered whether “we might not be overlooking some valuable contribution from the lore of our first Americans.”

In his new book, Being Scioto Hopewell: Ritual drama and personhood in cross-cultural perspective, Christopher Carr and his colleagues make a compelling argument that historically documented and contemporary America Indian traditions may indeed provide a key to unlocking the meanings of ancient Hopewell imagery.

Carr and his colleagues surveyed 204 stories from 42 historic Woodland and Plains Indian tribes that describe the journey the dead must take to reach the afterlife. Two especially prominent characters in many of these stories are Ferocious Dog and Brain-Taker.

Ferocious Dog guards a log over a swift flowing stream or deep chasm, which the souls of the dead must cross to reach the Village of Souls. According to a Miami Indian version of the story, the dog is enormous. This monster dog allowed only the souls of people who had been kind to dogs, or been good people in general, to cross.

Brain-Taker lives along the path to the afterlife and removes the brains from passing souls. According to Carr, removing the brain made the soul ”forget its earthly ties, worries, [and] emotional attachments,” so that it could have “a full happy afterlife.”

![The Hopewell culture is known for works of art made from raw materials obtained from far-flung places, including mica from the southern Appalachian Mountains and copper from southern Ontario. [Ohio History Connection]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/3JcWUNnprN_ZYgfbZ34uvg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTczMA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-columbus-dispatch/56a0d0d6de8fd9adf1cfdca52075548a)

These characters from historic Woodland Indian lore are perhaps embodied in a large Hopewell culture pipe recovered from Seip Mound in Ross County. The pipe was carved from soapstone in a style that was typical of Hopewell-related groups in northern Alabama. It depicts a dog gnawing on a human head, but the dog’s head is two-and-a-half times as big as the human head it holds between its paws, so Carr thinks the dog “is no ordinary earthly dog.” He proposes that the pipe represents a “Scioto Hopewell peoples’ combination of Brain-Taker and the ferocious dog into one character.”

Ferocious Dog/Brain-Taker also may be depicted on a beautifully crafted copper headdress excavated from Mound 13 at Mound City in Chillicothe. Although the exhibit at the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park visitors centers labels it a bear, the position of the legs and details of the head closely match those of the Seip dog.

Finding similar depictions of a monstrous dog at two separate Hopewell sites that match descriptions of Ferocious Dog/Brain-Taker from the stories of several Plains and Woodland tribes provides support for the idea that we can link ancient icons to particular indigenous oral traditions.

Henry Roe Cloud was right all along about what the lore of our first Americans might contribute to our understanding of Ohio’s ancient Indigenous cultures.

Brad Lepper is the Senior Archaeologist for the Ohio History Connection’s World Heritage Program

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Hopewell, later American Indian groups may share views of afterlife