Ancient Roman residences with 'pigeon towers' discovered in Luxor, Egypt

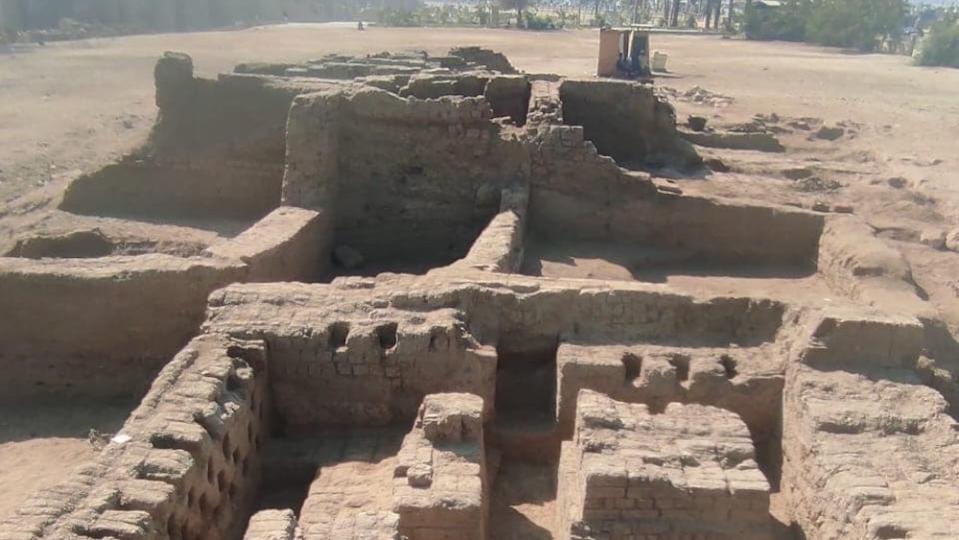

Archaeologists have discovered a residential area in Luxor dating to the time when the Roman Empire ruled Egypt.

A team of archaeologists from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities found a number of residential buildings, along with workshops and pigeon towers (where pigeons could be raised for eating), according to a ministry statement, which noted that this is the "first complete residential city" from the Roman Empire era found in east Luxor. A variety of artifacts were also uncovered, including pottery, bells, grinding tools (often used for food preparation), and Roman coins made of copper and bronze.

The residential area is close to Luxor Temple, a large religious center built during the reigns of several pharaohs before the Roman Empire, including Amenhotep III, Ramesses II and Tutankhamun. But the residential area dates to much later, during the second and third centuries A.D. During this time, Egypt was a Roman province and Roman emperors were sometimes depicted as pharaohs.

The team found that when the Romans took over Luxor, they started raising pigeons by erecting pigeon towers containing pots that the pigeons could use as nests, the statement said. Pigeons are the descendants of rock doves (Columba livia), which breed on rocky, coastal cliffs; but towers can mimic cliff conditions, making the birds feel right at home.

Related: 52-foot-long Book of the Dead papyrus from ancient Egypt discovered at Saqqara

Live Science contacted a number of scholars who were not involved with the research to get their thoughts.

Susanna McFadden, a professor of art history at the University of Hong Kong who specializes in Greco-Roman art, called the finds "exciting news." She is curious to learn how the team determined that the remains dated to the second and third centuries A.D.

She also wonders if there could be a relationship between this settlement and a military camp that was active in the area during the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian (reign circa 284 to 305). "It stands to reason that a residential area servicing the camp would have grown up outside the walls," McFadden told Live Science in an email.

Another scholar noted that this Roman residential area is not an entirely new find. The residential area in Luxor has "been known for a long time," Jacek Kościuk, professor emeritus at the Wroclaw University of Science and Technology in Poland, told Live Science in an email.

related stories

—Ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II's 'handsome' face revealed in striking reconstruction

—Stunning CT scans of 'Golden Boy' mummy from ancient Egypt reveal 49 hidden amulets

—Royal tomb discovered near Luxor dates to time when female pharaoh co-ruled ancient Egypt

Kościuk participated in excavations of Roman residential remains at Luxor that were carried out by an Egyptian-German team in the early 1980s. He sent Live Science two papers, published in 2011 in the journal Bulletin de la Société d'Archéologie Copte (Bulletin of the Coptic Archaeological Society), noting that while the 1980s team was able to survey only a small part of the settlement, they found the remains of Roman houses and baths.

While the existence of the Roman residential area was already known, the recent excavations unearthed a large portion of it, which may shed new light on what Luxor was like in Roman times. The new finds have "the potential to elucidate some critical research questions about Roman-era [Luxor], if the analysis is done carefully," McFadden said.