Ancient teeth offer new insight on how the Black Death emerged and spread globally

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Researchers believe they have finally pinpointed the origin of the Black Death, solving a 684-year-old mystery.

The second plague pandemic, which began in the 14th century and swept through Europe, Asia and elsewhere, killed millions, upended societies and even halted wars. For decades, researchers have chased leads and debated where the pandemic originated, with plenty of theories, but little certain evidence.

Now, new analysis of ancient DNA pulled from a burial ground in modern-day Kyrgyzstan dates the plague’s explosion to the year 1338.

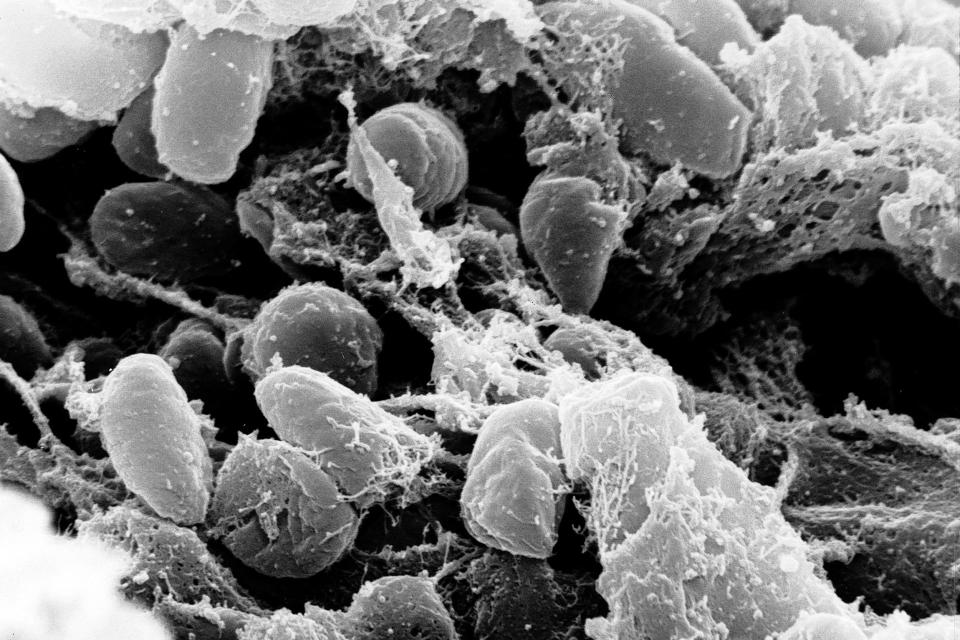

Researchers discovered DNA evidence of the bacteria that causes the plague inside teeth pulled from the bodies of several people buried there. The DNA is closely related to the strain that caused the Black Death less than a decade later and also to the majority of plague strains circulating today.

“What we found in this burial ground… was the ancestor of four of five of those lineages — so it’s really like the big bang of plague,” Johannes Krause, a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, said in a news conference. “So, we have basically located this origin in time and space, which is really remarkable.”

Krause and several co-authors published their findings Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The findings remove some of the guesswork from history, help researchers better understand how the plague pandemic moved across the world and tell more about the conditions that allowed the Black Death to emerge. The research also highlights rapid improvements in DNA sequencing, which could help scientists study the patterns of other historical diseases — and prepare for future outbreaks.

Some historians long suspected the burial sites examined in Kyrgyzstan had contained plague victims. Now, there’s physical proof.

“This is concrete evidence those people, who were previously suspected to have died from the plague, are known for sure to have died during the first stages of the Black Death,” said Sharon DeWitte, a bioarchaeologist and professor at the University of South Carolina, who has studied the Black Death for two decades but was not part of this research. “I am convinced by the findings.”

The pandemic swept across Europe in the 1340s with a reputation that preceded its onslaught.

In London, people set aside land for a burial ground before the plague even reached the city.

After hearing reports elsewhere in Europe, “they knew it was inevitable the plague would arrive and lots of people would die,” DeWitte said.

Most cities lost between 30% and 60% of their populations during widespread outbreaks, she said. The disease was caused by a bacterium that would later become known as Yersinia pestis.

There are several theories of how the bacteria spread in the 14th century. The most popular theory is that it was spread by biting fleas that accompanied black rats, which sometimes hitched a ride to new places with traveling humans. Another theory blames human fleas and body lice.

The Black Death marked the beginning of the second plague pandemic, which continued on for centuries.

“The pandemic lasted at least over 400 years,” DeWitte said.

For centuries, cities continued to weather outbreaks. Researchers differ on the pandemic’s end date. Some point to the Great Plague of London in 1665 as the period’s end, but the disease struck several other cities later.

The burial sites in present-day Kyrgyzstan, where excavations began in 1885, have piqued researchers’ curiosity for years. The sites, two Christian cemeteries, featured 467 tombstones spanning nearly 900 years, according to Philip Slavin, an author of the paper and an associate professor in history at the University of Stirling in the United Kingdom.

Some 118 of those grave markers were from 1338 and 1339, including some with inscriptions that were marked “pestilence,” but it hasn’t been clear exactly what that meant.

“Obviously, when you have one or two years with excess mortality, that means something funny is going on there,” Slavin said in a recent news conference. “And 1339 is just seven or eight years before the Black Death came to Europe.”

![Plague inscription from the Chu-Valley region in Kyrgyzstan, August 1886. The inscription is translated as follows: “In the Year 1649 [= 1338 CE], and it was the Year of the tiger. This is the tomb of the believer Sanmaq. [He] died of pestilence.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/lg.SbDHr.nDaLl3Eg3VZ3A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/nbc_news_122/b91c5fb0b3918085caec0644cfeba626)

The research team extracted seven teeth from seven people buried in the cemeteries during 1338 and 1339. The pulp of ancient teeth is filled with dried blood vessels and is most likely to contain evidence of bloodborne pathogens, such as the bacteria that caused the Black Death.

The researchers sequenced all the ancient, degraded DNA found within the teeth and pieced together disparate strands, which provided evidence of the bacteria’s presence.

Then, “we were able to target the entire genome and reconstruct the entire genome from these ancient bacteria,” said Maria Spyrou, the lead author of the new study and a researcher at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

The researchers found the strain identified in the cemeteries was an ancestor of genomes from victims of the Black Death about eight years later.

They also discovered that marmots living today in the Tian Shan mountain range near the burial site carry a closely-related strain of the bacteria.

Researchers believe the Black Death strain emerged there, possibly from the marmots, and then spread rapidly in the community where the burial sites were located. The community — which is near Lake Issyk-Kul in present-day Kyrgyzstan — had about 1,000 people living there before the disease hit, according to Slavin.

It was a trading post along the Silk Road, with people of many ethnicities and backgrounds. Trade and travel likely sent the plague to other regions.

Spyrou said that determining where the Black Death originated gives researchers a foothold to understanding what factors led to the pandemic.

The research was made possible, in part, by the technological advances in genetic sequencing, which has become more powerful and cheaper. Future work could open doors to understanding other historical disease outbreaks.

“To be able to analyze the entire genome of the strain that existed 700 years ago — it’s extraordinary,” DeWitte said. “People are excited about looking at other diseases of the past.”

Plague remains a concern today, mostly in rural areas. It can be treated with antibiotics. Improvements in hygiene have greatly reduced transmission.

Still, some countries have faced large outbreaks. Madagascar in 2017 reported more than 2,400 cases of pneumonic plague, which can spread through the air.

Krause said the Black Death research — and the world’s experience of the coronavirus pandemic — calls for more emphasis on understanding what diseases animals are hosting that could spill over to humans.

The animal spillover that caused the Black Death has some resemblance to the diseases making headlines today.

“We really have to increase our efforts to understand the diversity of pathogens in animal reservoirs — to monitor them,” Krause said.