Anderson County’s coal mine explosions led to improved mine safety

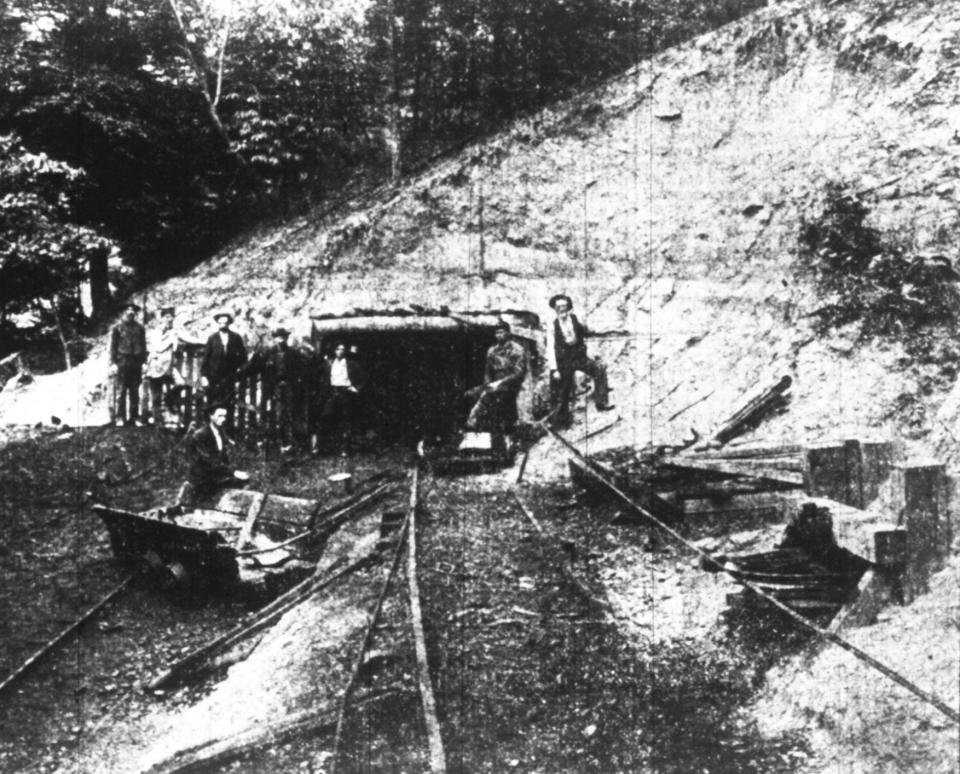

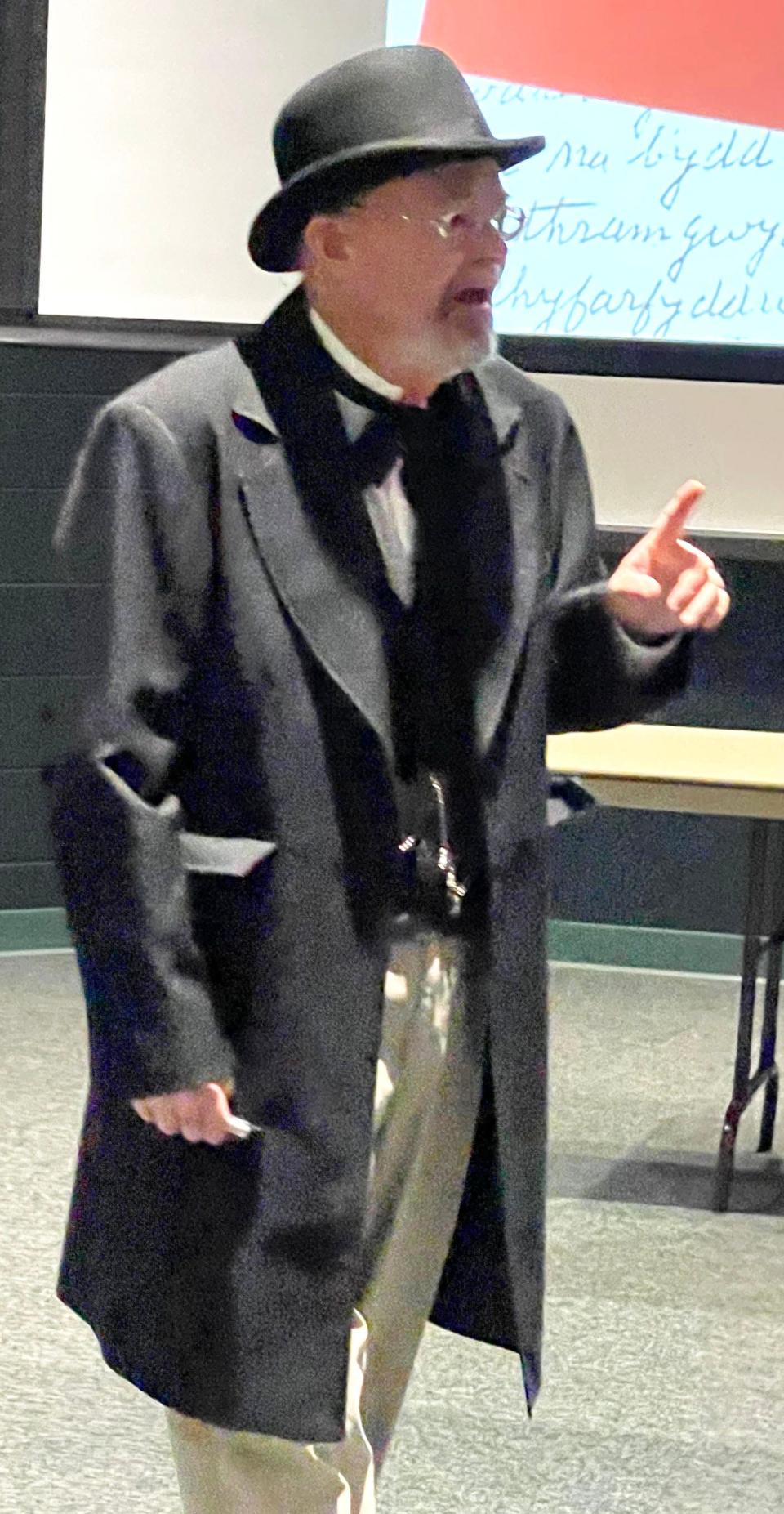

In this second in a three-part series of articles on Coal Creek history, as presented at the Coal Creek Miners Museum, 201 S. Main St., Rocky Top, Carolyn Krause draws on a recent talk by Knoxville engineer Barry Thacker on coal mine explosions early in the 20th century in Anderson County and their national impact. In his recent hour-long presentation on “Bringing Coal Creek History to Life” at the Oak Ridge Branch Campus of Roane State Community College, Thacker portrayed David Thomas, a Welsh mining engineer who lived in Coal Creek and witnessed its historical events. Coal Creek later was named Lake City, as a gateway to Norris Dam, and now is called Rocky Top.

***

After the Coal Creek War ended and convict labor was abolished in 1892, the Welsh community prospered for 10 years in Coal Creek and Briceville, where opera houses were built. The mining engineers in Coal Creek, such as David Thomas, had read newspaper reports about explosions involving methane gas in deep mines in Dayton, Tennessee. But they weren’t worried about the Fraterville mine, which had been one of the safest mines in the state since it opened in 1870.

On May 19, 1902, the Fraterville mine exploded. Friends and relatives of the 216 miners underground gathered outside and hoped the miners would escape the mine alive. Thomas, then an engineer for the Provident Insurance Co., was a member of the rescue crew.

In the worst mine disaster in Tennessee history, 190 men and young boys from the Fraterville community were killed instantly. The cause: a coal dust explosion that sent debris and toxic methane gas belching from the air flow shaft and out through the mine’s entrance.

Coal mining was one of the most profitable professions for men without a college degree. For every position, three men applied because no welfare was available. The Fraterville mine manager encouraged all male family members to work in the mine. Only three adult males were alive in the Fraterville community after the 1902 disaster. Family losses ranged from all their male members to five brothers and two brothers-in-law, a father and three sons and eight cousins who all worked in the same mine.

The many widows often married miners who came to replace those that died. One enterprising widow supported her family by using the coal company funds she received as a down payment for a boarding house. She leased rooms to miners arriving in the area.

According to Thacker, it had been known for hundreds of years that coal mine explosions emit poisonous gases like carbon monoxide, so miners “try to find a room in the mine where the air is good and build a barricade to keep out the poisonous gases. Unfortunately, if rescuers don’t get there in time, those individuals will suffocate as the oxygen in the air is depleted. But at least they have hours rather than minutes to survive.”

When Thomas and the rescue crew entering the Fraterville mine located a barricade, broke it down and entered the confined space, they found 26 deceased miners. Ten of those miners had written farewell letters that the crew collected and gave to the families. Powell Harmon wrote an extensive note to his family that included these words: “I hope to meet you all in heaven. My boys, never work in the coal mines.” (His eldest son Condy at age 15 had to work in the Cross Mountain mine to support his family. He died a family hero at age 24 in that mine’s 1911 explosion.) Replicas of those letters can be read at the Coal Creek Miners Museum in Rocky Top.

The farewell letters, which shared a theme of God and family, “were published in newspapers around the world,” Thacker said. “For the first time, people in New York City, Boston and Washington, D.C., could read about the perils of being a coal miner in Appalachia. The articles raised public awareness about the dangers of early 20th century coal mines.”

Newspaper coverage of the Fraterville mine explosion sparked a public outcry over coal mine safety. Congress established the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1910. Its mission was to improve mine safety. The bureau required rescue crews to wear self-contained breathing apparatus and recommended that crews start using a canary in a cage to test air quality in mines.

“A canary will die long before a human if there’s bad air in the mine,” Thacker said.

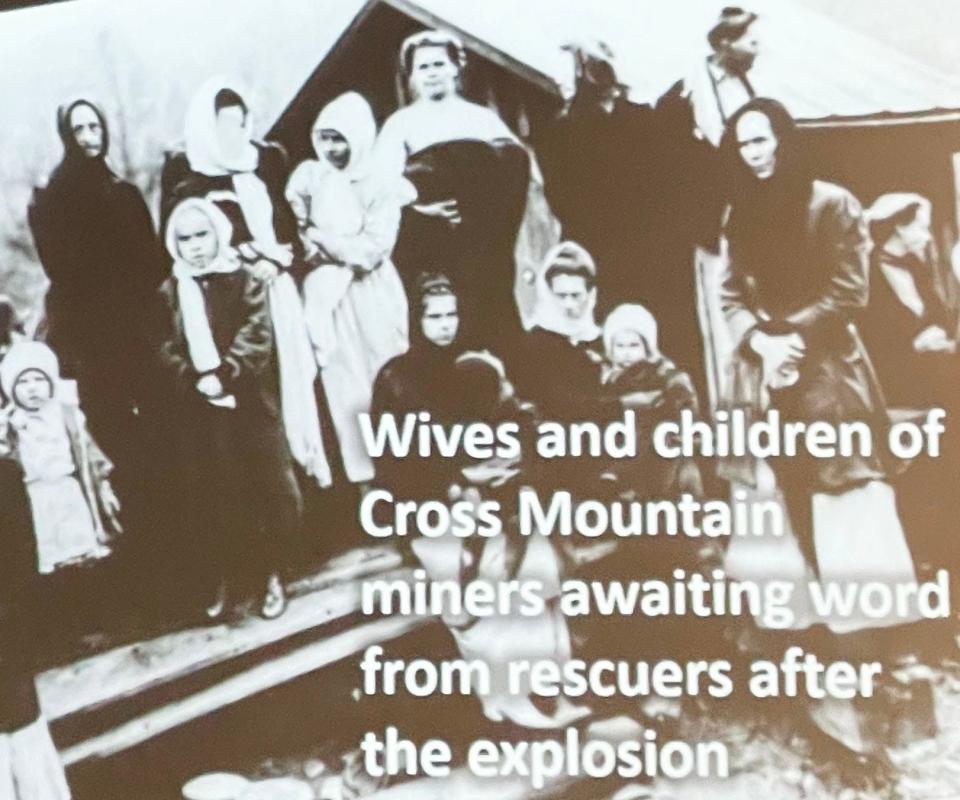

The Bureau of Mines was first able to test its safety measures on Dec. 9, 1911, when the Cross Mountain mine in Briceville exploded. In his book “70 Years in the Coal Mines,” Welsh miner and mine owner Philip Francis wrote these passages about his role during the rescue efforts after the Fraterville and Cross Mountain mines exploded. “On arriving at the mine, women and children were weeping and all in great distress. Once again, I must control myself and not let my sympathy weaken me. ... For I had a duty to perform to a fellow miner. So, I went into the mine with 40 men. ... I met a man with a small cage with a dead canary in it. I met another man with a gas mask on and carrying his oxygen with him.”

After the Cross Mountain mine explosion, George Camp (the son of Thomas’ former boss at the Fraterville mine) sucked air from the Cross Mountain mine out through the connecting Thistle Switch mine.

“That quick action by George Camp gave time for the rescue efforts at Cross Mountain,” Thacker said. “So, 50 hours after the explosion, the rescue crew found 16 surviving miners behind a barricade the crew broke through. Their canary lived, showing that the air was good, and they were able to rescue the miners.”

Although 84 miners died, the Cross Mountain mine disaster marked the first successful rescue of coal miners from a U.S. mine that had exploded,” Thacker said. “It was the first use of canaries to test air quality and the first use of self-contained breathing apparatus by engineers with the crews of the U.S. Bureau of Mines. The famous phrase ‘canary in a coal mine’ as a harbinger of danger originated in Anderson County at the Cross Mountain mine in Briceville!”

The Cross Mountain mine rescue crew were considered heroes and the group photo graced the cover of Popular Mechanics magazine. The historical significance of the Anderson County mine explosions is that they led to life-saving mine safety regulations and equipment.

“More coal is mined today in the United States than was mined back in the early 1900s,” Thacker said. “Yet the fatality rate for miners today is 99.9% lower than it was at the turn of the 20th century.”

Clearly, Welshmen in the area had an important impact on Anderson County, state and U.S. history.

“Most of the Welsh miners who died in the Fraterville and Cross Mountain mine explosions were the same miners who fought to end convict leasing,” Thacker said.

They were the same miners who helped end Black slavery in Tennessee. Their fate was to die in mine disasters that resulted in improved safety for American miners of black coal.

***

In the next "Historically Speaking" column and third in this three-part series, Carolyn will bring us more on David Thomas, Briceville Elementary School students who became Coal Creek Scholars and their relationship to a professor and author at Harvard University who specialized in Welsh literature and history.

D. Ray Smith is the city of Oak Ridge historian and longtime "Historically Speaking" columnist for The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Anderson County’s coal mine explosions led to improved mine safety