Andrew Price School: A once-hidden history casts doubt on a congressman’s legacy

The white, wooden building on the Thibodaux-bound side of La. 24 has long been an unofficial landmark of sorts, a recognizable Schriever place-marker.

Andrew Price School has served various purposes for the Terrebonne Parish School District since its construction in 1919, and discussions continue as to how it might be used now. Its namesake had an illustrious career. But allegations of his involvement in an infamous and deadly racial incident beg the question of whether an official building should continue to bear his name.

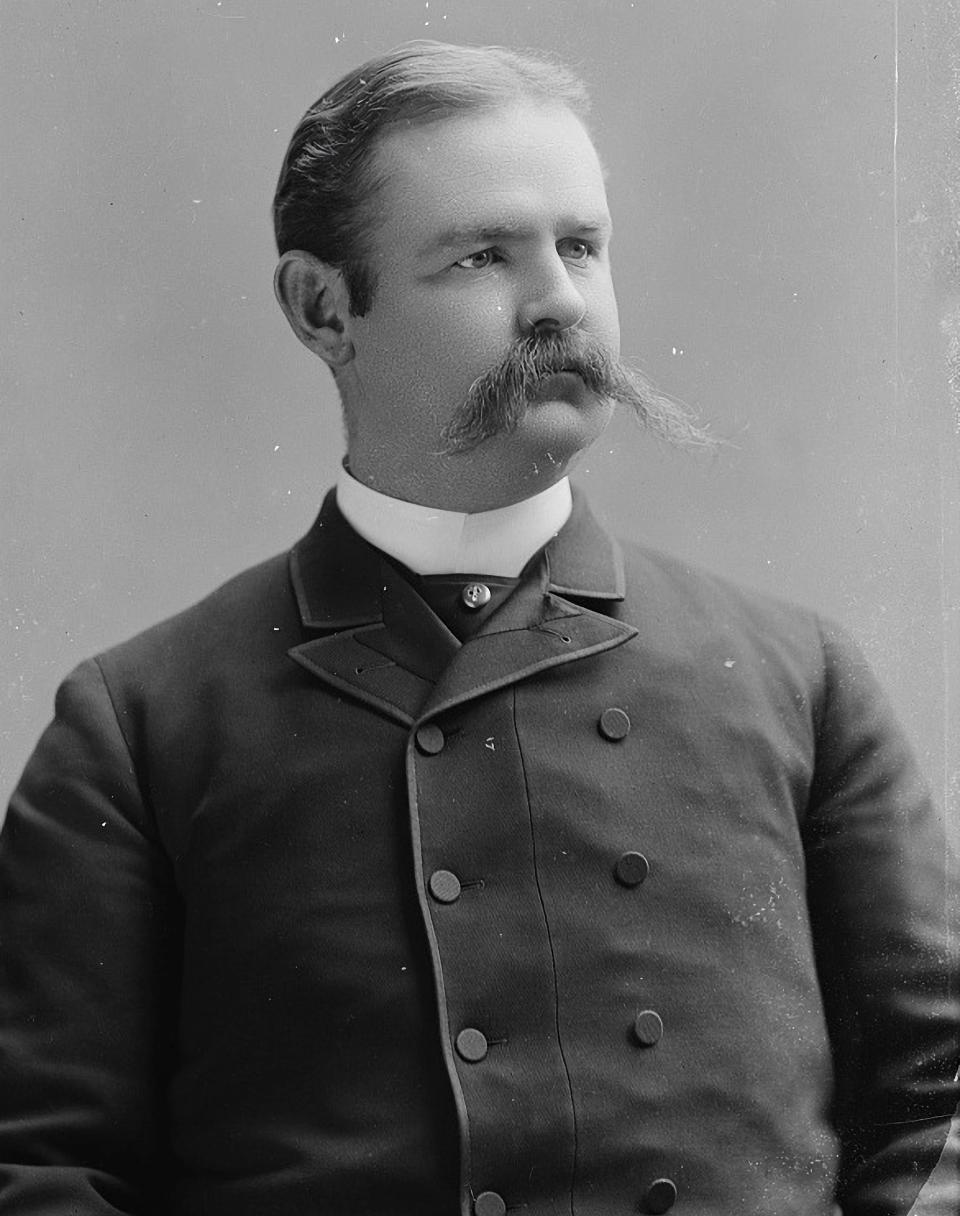

Andrew Price was a St. Mary Parish native born in 1854, the son of slave-owning sugar-cane planters, who went on to practice law.

A national trend: 82 schools have removed their racist namesakes since 2020. Dozens now honor people of color.

In 1879, he married Anna Margaret “Nanny” Gay, daughter of Iberville Parish sugar baron Edward J. Gay, and went on to manage one of his father-in-law’s holdings, Acadia Plantation in Thibodaux. Edward Gay, meanwhile, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1884.

Edward Gay died in 1889, and Andrew Price was elected to fill the vacancy, holding the congressional seat until 1897.

A biographical sketch published in 1914, five years after his death, describes Price as a man of “genial and generous nature, … extremely popular with all who knew him, while his brilliant intellect and solid education highly fitted him for the public life he had begun with such admirable prospects.”

Trouble in the fields

Price, like other local planters, was sorely affected by a strike of Black sugar-cane workers seeking better pay and working conditions on the cusp of the 1887 harvest season. Like others counted among Thibodaux’s most prominent residents, he was appointed to a “Peace and Order” committee created in response to tensions related to strikers seeking refuge in the town after eviction from plantations for their involvement.

The shooting of two white volunteer sentries at dawn Nov. 23, 1887, resulted in a violent response throughout Thibodaux and the shooting deaths of an estimated 30-60 Black men and women.

A plantation mistress, Mary Pugh, in letters to relatives, alleged Price’s involvement.

One of her sons “bolted right in the midst of it when he heard the fighting,” Pugh wrote, stating that Price — captain of a militia company — sent the young man home to her.

She then described how Price’s militia company found an alleged strike leader in the loft of a house. According to Pugh — no ally of the strikers by any means — the Black man was told to run for his life and then an order was given to fire.

“All raised their rifles and shot him dead,” she wrote.

If Price had been close enough to the action to send Pugh’s son home, logic might dictate that he was likely with his company of militia men when the shooting she described took place.

“This is something we don’t have completely documented,” said Thibodaux historian and author David Plater, a descendent of the Gay family and therefore kin to Price. “I would say that he was not involved, but I don’t know. I think [Pugh’s] description doesn’t fit his character. I would think he was more likely involved with trying to keep the peace on Acadia Plantation.”

'For public school purposes'

Ironically, the land on which the Andrew Price School building sits — former St. Bridgette Plantation land — was donated in 1919 by Nanny Price, Andrew Price’s widow, according to school district records, with the provision that it must always be used only “for public school purposes.” According to some family recollections and those who had studied the family’s history, it was always Mrs. Price’s desire to have a school that could serve the workers on the family’s plantations.

This was done, in a sense, with the school ironically dubbed the “Schriever Colored School,” as it was founded when schools in Terrebonne Parish and across the South were segregated by race.

The school did not bear the name of the congressman until a request for that was made by the late Richard Plater — brother of David Plater — in 1951, and it has been called that ever since. The building is now used for district storage and in the past was home to the parish’s school program for troubled children.

Time for a change?

“I think that when you consider the history of Andrew Price’s role in the Thibodaux massacre, it would be only right to take his name off of a school building or any building,” said Lafourche NAACP President Burnell Tolbert, who wrote the introduction to the 2016 book “The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike,” which includes the allegations concerning Price’s involvement with the atrocity.

Price’s alleged involvement in the massacre was not generally known until 2016 and is still not common knowledge among school district officials. But so far none have come forward to suggest that his name be removed from the school.

Some who have been made aware of the history — including Terrebonne School Board member Greg Harding — are taking a cautious approach.

“I’m not too fond of having a school named after someone where that kind of history is possible,” Harding said. “But can we take the word of one individual? The problem I would see is that further documentation would be very important.”

Next in the series: Looking forward. John Kelly DeSantis is a freelance journalist and a former reporter for the Houma Courier and Thibodaux Daily Comet. He is the author ot the 2016 book “The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike,”

This article originally appeared on The Courier: Andrew Price School: Amid the cane fields a once-hidden history lingers