Angry mobs, deep divisions: Canada's politics shaken up as election fever builds

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

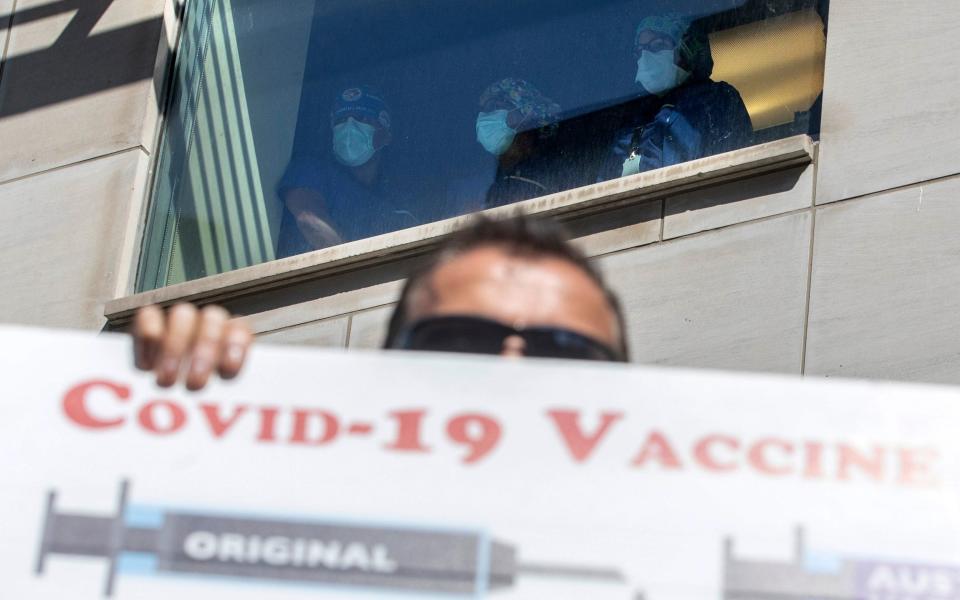

On "Hospital Row" in downtown Toronto, the strip of road home to five of the city's major medical centres, a group of protesters stood and shouted: "where's the pandemic?"

Some wore the red hats and t-shirts redolent of Donald Trump's "MAGA" movement as they shared conspiracy theories about Covid-19 and opposed "tyrannical" vaccine mandates.

The baseball caps read: "Make Justin Trudeau a drama teacher again", a play on the former US president's campaign slogan. One protester even clutched an American flag superimposed with a Maple Leaf.

The 200-strong crowd chanted "freedom" as they picketed the hospitals, others turned to members of the press and yelled "fake news".

It was one of dozens of orchestrated protests in major towns and cities across Canada this week, as the country faces a fourth wave of Covid-19 infections and a general election.

“You guys are going to have rocks thrown at you next,” one man is yelling at us, calling us “traitors to our own people.”

“There’s no pandemic,” one man yells. pic.twitter.com/7OsuUPbGP1— Jenna Moon (@_jennamoon) September 13, 2021

In the country with one of the highest coronavirus vaccination rates in the world, the mass outpouring of anger has caused alarm.

The recent wave of unrest has drawn comparisons with the US, where the public's views on the pandemic response have long fallen along partisan lines.

Canadian demonstrations have adopted the slogans and symbols of the neighbours to the south. American flags, signs reading "don't tread on me" and the "thin blue line" flag of law enforcement, now adopted by the US far-right, have been present in recent protests in Canada.

The political spillover does not end there. Two of the organisers of this week's protests in Canada, Kristen Nagle and Sarah Choujounian, are known to have been present at the January 6 rally in Washington DC which ended in a pro-Trump mob storming the Capitol. There is no suggestion the pair were involved in the violence.

Some social commentators argue the small but prominent protests reflect tensions that have been simmering below the surface of Canadian society for some time.

But it is the snap election, called last month by prime minister Justin Trudeau to strengthen his mandate, which has brought them to the fore.

"The partisans of the major parties have come to dislike each other just as intensely as American partisans dislike each other," said Richard Johnston, a political scientist at University of British Columbia.

"In fact their numbers may be small, but their actions are, if anything, more aggressive than in the US," he said. "I'm not aware of blocking emergency entrances to hospitals in the US."

Mr Trudeau's election campaign, which the Canadian premier has centred on his handling of the pandemic, has become a lightning rod for the protesters.

At a recent campaign stop in London, Ontario, an anti-vaccine mob pelted gravel at Mr Trudeau and nearby journalists.

The protesters waved Canadian flags chanting "lock him up", the phrase Mr Trump's supporters use for political opponents.

Safety concerns around the protests have forced the Liberal Party leader to cancel at least one campaign event and stop sharing details of his itinerary with the press.

Mr Trudeau, 49, seemed to crack under the strain of the abuse this week, when he lashed out at a man who stood hurling abuse at him, including a sexist slur about his wife.

"Isn't there a hospital you should be going to bother right now?" the prime minister yelled back.

The virulent anti-vaccine movement has overlapped with a rise in popularity of the far-right People's Party of Canada (PPC), whose purple emblems are a fixture at the protests.

Led by Maxime Bernier, a former Conservative politician nicknamed "Mad Max", the party has successfully channelled lockdown fatigue and vaccine scepticism into a surge in the polls.

The populist party currently has nine per cent support nationally, according to an EKOS poll, overtaking the Green Party with a huge boost to the 1.6 per cent it received in the 2019 election.

More than 100 PPC supporters gathered at the final leaders debate of the election in Gatineau, Quebec to express their frustration with the major parties.

Among them was Paul Heinlein, a 40-year-old from Yorkshire, who now runs a software development business in Canada.

He told The Telegraph he had become concerned about the incursions on personal freedoms during the pandemic.

"This election gives the people a chance to voice their disapproval of all the bad decisions that [politicians] are making," he said.

Irena Mariajancevic, a pharmacy technician in her 40s, said she had come to distrust officials' advice on vaccines after doing her own research.

She indicated the crowd around her as she described the "sheer amount of anger" many in the country felt towards those in government.

Others turned their fire on members of the public and the press who had chosen to wear face masks. "You look like oppressed people," one man with a megaphone shouted.

Andrew McDougall, a Canadian politics professor at the University of Toronto Scarborough, warned it was premature to draw "too many conclusions" from angry scenes on the campaign trail.

"Canadians have always been a little self-flattering when it comes to their politics about how we haven't had these vitriolic incidents," he said.

He added that while the rise of the hard-right PPC was "new in Canadian politics" and "concerning for a lot of people", it remained to be seen whether the party's shift from the fringes to political significance would be confirmed at the ballot box.