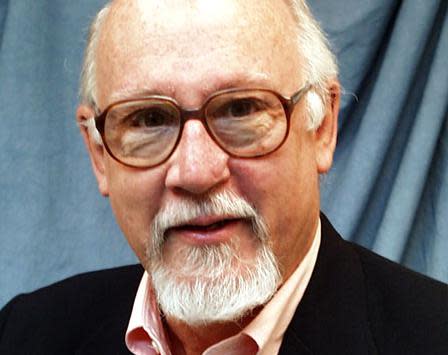

Ann Bedsole's autobiography shows how she took her father's advice | DON NOBLE

Like many of us, Ann Bedsole felt it wise to stay close to home during the COVID pandemic.

Rather than just killing time while avoiding dying, she decided to use the enforced seclusion to write her autobiography, and the result — "Leave Your Footprint" — is more revealing and candid and amusing than one would expect from a very well-known public figure.

Born in Selma, in 1930, but raised mostly in Jackson, Alabama, Bedsole had an idyllic childhood. She writes it was “glorious,” “wonderful.” These days, when most memoirs and autobiographies are sagas of suffering and pain, that is a rarity.

More: Black sisters try to escape from 1964 Mississippi | DON NOBLE

The Depression was on. Nevertheless, in 1935, her father, the manager of a sawmill, made the “bold move” to buy a sawmill. Over time White Smith would own several mills and 60,000 acres of timber.

Bedsole and her sister “idolized” their father, a handsome, 6 foot, 1-inch, authoritative man.

His masculinity, however, was not repressive or patriarchal in the negative sense. He told his daughters repeatedly that girls could do anything boys could do, and “don’t go through this life and not leave something of value. Don’t forget to leave your footprint.”

Bedsole has certainly done that.

The story moves through her childhood, with summers at a much simpler Gulf Shores, with the polio scares we all experienced pre-Salk, to her first marriage. Her husband “made two mistakes. He had a brief affair, and, second mistake, he told me about it. I was deeply offended and refused to forgive him, so we divorced.”

Bedsole would marry again, to Palmer Bedsole, and they would stay married for half a century and learn to get along, but her honesty compels her to say “I wish I could say that Palmer was the love of my life … that we were never happier than when we were together. But it wouldn’t be true.”

Her marriage in public, she admits, was a “charade.” She really didn’t like Palmer’s uncle Linyer either. He was mean to her children.

If Bedsole can be this candid about her marriage and family it is no wonder then that she speaks her mind about the politicians she knew while serving in the Alabama House and then Senate.

She is, as all Alabamians know, one of the founding mothers of the state Republican Party. Her low opinion of George Wallace fueled some of that. He was “embarrassing, mean-spirited, and race baiting.” And, later, on a trip to Asia, mentally incompetent.

She also felt that Alabama needed a two-party system because of the ferocious corruption of the Democratic Party. Voter fraud was rampant and obvious. Eisenhower, a very popular presidential candidate, got no votes in Leroy, Alabama. None. The Democratic boss there said so.

It was impossible to do business in Washington County, she tells us, unless you put Boss Ed Turner on retainer.

As Bedsole’s political career moved along, she would have conversations about how many votes she would be “allowed” in Washington County.

Voting machines, thankfully, put a stop to the worst of the voting corruption.

As one of very few, or at times, the only woman in the state Senate, she has a lot to say about misogyny in the Legislature, which was obvious and harsh.

She persevered, however, even when told often, to her face, women should not ever serve in government.

Perhaps the most obvious male chauvinist, because not very bright, was Gov. Guy Hunt, who didn’t care for educated people, was "nasty and ugly to me," "hated women" and "had no respect for women or their opinions."

Tom Parker, she tells us bluntly, "who made his name for being one of Roy Moore's stooges," was “almost as crazy as [Roy] Moore.” Parker, at present the chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, is a "horrible man."

Her favorite Democrat of all time was Bill Baxley who “treated everyone decently” and comforted Bedsole in her losses: in Alabama, he said, “The dumbest one always wins.”

Less amusing, but massively impressive, are the civic achievements of Bedsole’s post- political life. The list is immense: valuable natural conservation work, a founder of the Mobile Historic Homes Tour, and the founding of the Alabama School of Math and Science. She organized the Mobile Tricentennial and established the Family Village for homeless women. And much more.

Even now, at 93, Bedsole is, she insists, not quite done leaving her footprint. She writes : "I've told my doctors they've just got to give me three or four more good years. I have things I absolutely must get done."

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Leave Your Footprint”

Author: Ann Bedsole

Publisher: Ann Bedsole

Pages: 337

Price: $29.49 (Hardback)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Book shows how Ann Bedsole took her father's advice | DON NOBLE