What the anniversary of the Great Cascadia earthquake might tell us about 'The Big One'

Anyone who's lived in the Pacific Northwest for any length of time has likely heard of "The Big One."

Friday marked the 324th anniversary of the last Great Cascadia earthquake, an estimated 8.7 to 9.2 megaquake that rattled the Pacific Northwest and caused major tsunamis across the Pacific. Three centuries later, scientists are trying to use that earthquake to determine whether The Big One is a real possibility, and just how big it might be.

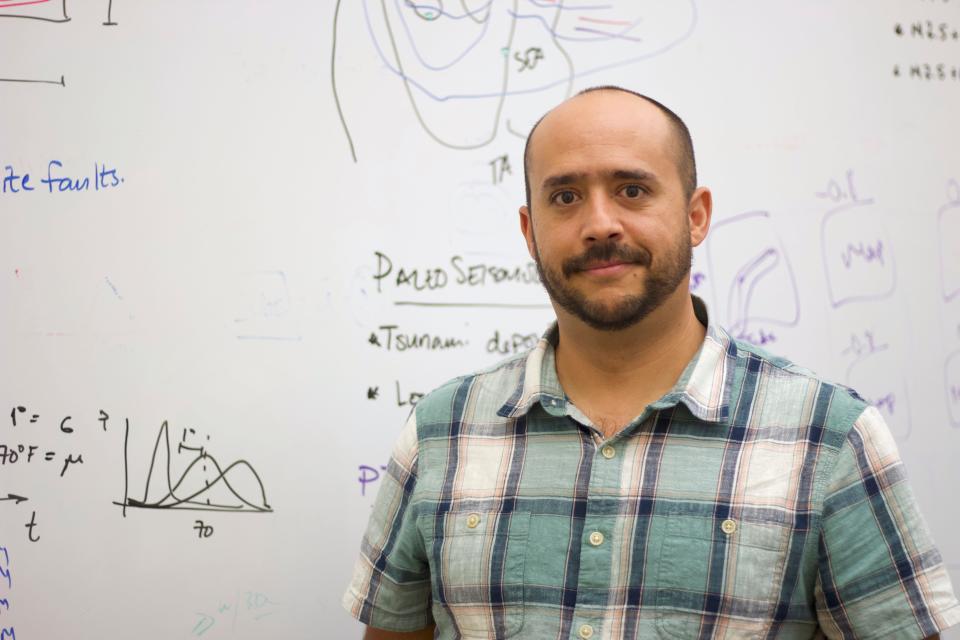

Diego Melgar Moctezuma, associate professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Oregon and director of the Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center, said studying the past could provide important clues for what to expect in the future.

"It's the most important earthquake for us in the region," Melgar Moctezuma said.

The 1700 mega earthquake

At around 9 p.m. on Jan. 26, 1700, the ground shook for one to two minutes, scientists estimate, when a massive rupture occurred along the Cascadia subduction zone.

Spanning about 600 miles underwater between Northern California to British Columbia, the subduction zone is centered about 100 miles west of the Oregon coast. A subduction zone occurs when two offshore tectonic plates meet, one sliding underneath the other, building up pressure over time.

For decades, due to the erasure of Indigenous knowledge and colonization, the majority of inhabitants in the Pacific Northwest assumed there were no earthquakes in the region. However, through hints in the landscape and remaining oral histories, scientists began putting the pieces together. Melgar Moctezuma said scientists have had to rediscover much of the history and knowledge.

Scientists began picking up interest in the possibility of large earthquakes in the area in the 80s, but there were very few researchers at the time. It began gaining more traction in the 90s.

Since then, key findings like tsunami sands and ghost forests have been found all along the West Coast from Northern California up to British Columbia, Melgar Moctezuma said. Tsunami sands can be found embedded in the landscape, where it could not have arrived without a tsunami. Ghost forests can appear due to tsunamis, when salt water floods into a coastal forest below sea level, causing the trees to die. Melgar Moctezuma said scientists can look at tree rings to indicate when those trees died.

Through this evidence, scientists believe the subduction zone ruptured along 600 to 700 miles.

"That would mean widespread shaking, landslides and tsunami impacts across that 700-mile stretch of coast and the inland regions, probably as far inland as at least Eugene, Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, Redding in California, and so on, with maybe even strong shaking felt as far inland as the other side of the Cascades," Melgar Moctezuma said. "Places like Bend might even feel not super violent shaking, but shaking strong enough to see some minor damages.

"We actually know a lot about it for such an old event. It's not always true for earthquakes of centuries past."

Melgar Moctezuma said the conditions in the Pacific Northwest allowed much of this evidence to be preserved over hundreds of years.

Another big clue that scientists put together was through record-keeping in Japan. Those accounts reported an "orphan tsunami" in 1700. Melgar Moctezuma said it was called an orphan because Japan didn't feel an earthquake before the wave. By looking at the geological evidence in the Pacific Northwest, scientists were able to link the 1700 tsunami in Japan to the Cascadia earthquake. The Cascadia quake created a tsunami that hit Japan about nine hours later.

"When people put all of that together, there was really only one explanation," Melgar Moctezuma said. "Modeling shows that it has to be an earthquake from here to get to get all the way to Japan. People looked at whether it could be an earthquake in Alaska, whether it could be an earthquake in Mexico or Chile or other parts around the Pacific to make the tsunami as big as it was in Japan. When we put all of it together, it has to be from here."

By the early 2000s, the 1700 earthquake and the Cascadia subduction zone became more widely accepted.

"Now, we work more debating details and intricacies and nuances of will just how long was it? How far inland can it go? Is it (every) 300 years or 400 years and that kind of thing happens?" Melgar Moctezuma said. "But overall, by the early 2000s, we were pretty confident that we knew that this place made big earthquakes."

What the past can tell us about the future

Melgar Moctezuma said it's important to know this scale of earthquake is still possible in the Pacific Northwest.

While the 1700 earthquake is what scientists know the most about, they have been able to find evidence of eight to 10 other past Cascadia quakes. These large-scale seismic events seem to happen every 300 to 500 years, they've found. It has now been 324 years since the last quake.

"That gets the mind wondering about how far along we are in this process in getting ready for the next one," Melgar Moctezuma said.

If a quake similar to the 1700 event were to happen now, researchers say it would have significant impacts: an estimated 10,000 casualties, thousands of buildings destroyed and thousands of households displaced. Depending on the location, it could take weeks to years to restore basic utilities.

Scientists estimate there is a 37% likelihood of a 7.0 magnitude or higher earthquake in the next 50 years, while there is a 14% chance of a 9.0 magnitude or higher earthquake in the same time frame.

Subduction zones can be found across the globe, many of which have similar patterns of hundreds of years between large earthquakes. However, what sets the Cascadia subduction zone aside from other subduction zones around the world is the lack of "smaller" earthquakes, according to Melgar Moctezuma.

"We don't get magnitude 6's, we don't get magnitude 7's, we don't get magnitude 8's, which is both a blessing and a curse," Meglar Moctezuma said. "We don't have to put up with that damaging shaking because (those) can be very damaging. ... It's difficult or bad in the sense that it makes it challenging to rally people to the cause of being earthquake-ready because we haven't felt an earthquake in so long and so people can say, that doesn't happen here."

Preparing for future quakes

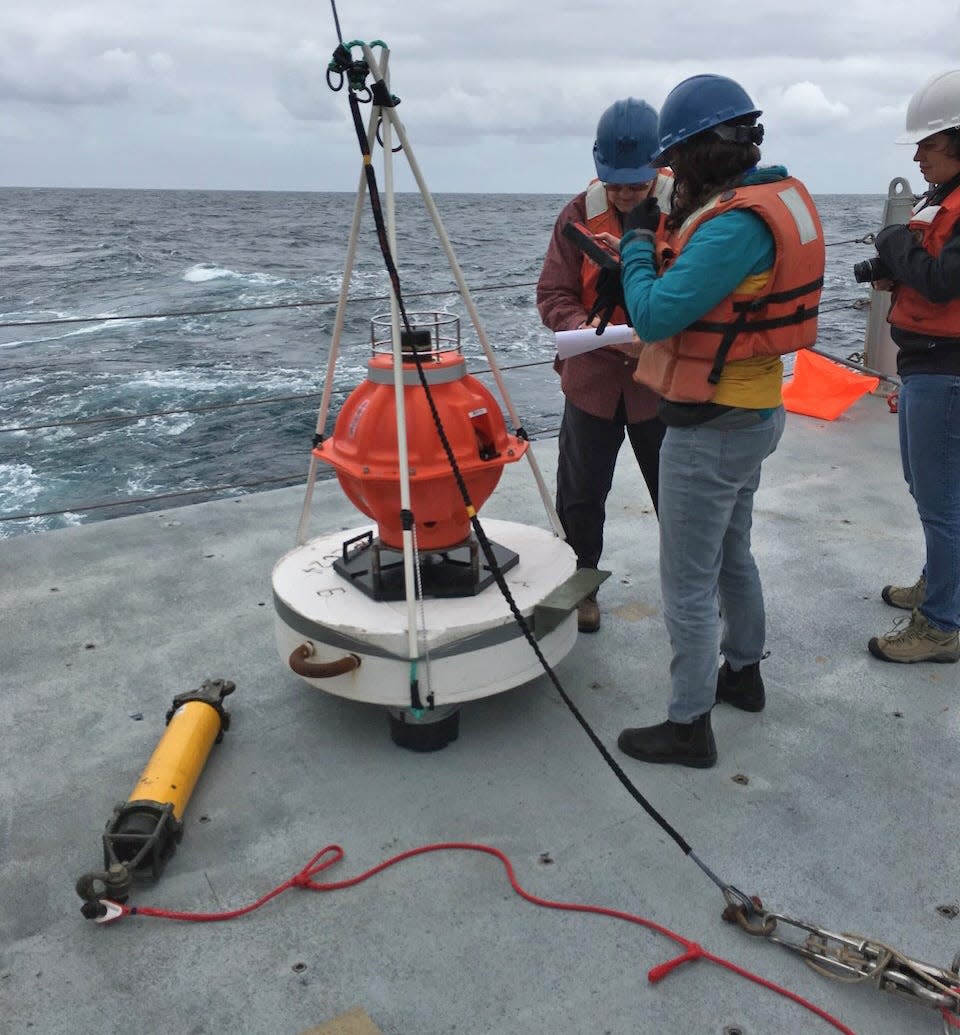

CRESCENT, a multi-institutional center that studies the Cascadia subduction zone, officially launched in October. While still in its infancy, Melgar Moctezuma said the center is making gains, having hired a full staff, moved into its new offices, and now recruiting undergraduate and graduate students.

"We are operational," Melgar Moctezuma said. "We're carrying out research and we're meeting with partners and government agencies all over the place. We're very much almost going in at full steam. Research results will start to happen soon."

While CRESCENT does not push for preparation or infrastructure readiness, the center's research and published articles will inform agencies on how to adjust building codes, for example.

"We don't want to sit around and just despair and be waiting to die, that's not a good attitude," Melgar Moctezuma said. "What you need to know is how to prepare... The only way to build a resilient society for the future is to have a deep understanding of what has happened before."

Additionally, there is still much that is unknown or still up for debate around the Cascadia subduction zone and its earthquakes. Research is being done on whether the entire zone will break at once, or if there will be two separate ruptures. If there were two separate ruptures, would they happen hundreds of years apart, or would they be within the same month, similar to the earthquakes in Turkey in 2023.

"There's a lot of things we don't know," Melgar Moctezuma said.

Common misconceptions about 'The Big One'

As far as The Big One is concerned, there is still an abundance of misinformation that can confuse. Melgar Moctezuma said there are several common misconceptions:

Myth: Earthquakes are more likely to occur at a certain time or day or season. Fact: Earthquakes can happen at any time.

Myth: Scientists can predict when exactly an earthquake will happen. Fact: While seismology has come a long way, predicting the date and time an earthquake will happen is still not possible.

"We're very far away from being able to do that," Melgar Moctezuma said. "What we can do is what I just described, which is forecast that if it happens, we have a pretty good idea of what it's going to look like."

Myth: A tsunami from The Big One will come into the Willamette Valley or into Portland. Fact: Tsunami can travel several miles, even tens of miles, but will mostly affect the coast.

"The tsunami is at the coast," Melgar Moctezuma said. "How far up the Columbia River the tsunami is going to come, that actually, I don't know the answer to that. I'm not aware of any serious modeling studies, it probably will go several miles, maybe 10s of miles even up the Columbia River. But it'd be very difficult to think that it would make it all the way to Portland, for example. But it would definitely have impacts on the Columbia River Estuary."

Myth: The Big One will be accompanied by a series of volcanic eruptions. Fact: Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes have a slight connection, a volcano would not inherently erupt because an earthquake occurred. While it's possible, it is not likely.

"There is evidence that following big earthquakes, volcanoes get a little uncomfortable, and they maybe start having like little explosions of ash and steam," Melgar Moctezuma said. "There is a sense that there's a weak connection between the earthquakes and the volcanoes, but it's not like following the earthquake all the volcanoes like Mount St. Helens and Sisters and so on are gonna go crazy. It's not like that. But if we saw all of a sudden more steam coming out of Mount St. Helens after a big earthquake, that would be kind of expected."

To find out more about Melgar Moctezuma's work and CRESCENT, visit cascadiaquakes.org.

Miranda Cyr reports on education for The Register-Guard. You can contact her at mcyr@registerguard.com or find her on Twitter @mirandabcyr

This article originally appeared on Register-Guard: Can the Great Cascadia earthquake help predict 'The Big One'?