Another killing, another cover-up. Patients remain at risk at Florida mental hospitals

Angela Barrett lost her father twice: First, during her childhood in Miami-Dade, when the ravages of schizophrenia robbed him of his mental acuity, and again, decades later, when state mental health administrators assigned him to the same bedroom as a man who once sliced his own mother’s throat.

It was Northeast Florida State Hospital’s job to protect Warren Barrett, who had been committed to the state’s care following several failed suicide attempts. But Barrett’s roommate, Mark Stone, who had a long, frightening history of violence, was able to accomplish what Barrett had repeatedly failed to do himself.

He killed him.

Barrett, who was 72, became another casualty of the Florida Legislature’s long-standing decision to ration care at psychiatric facilities for patients like Stone. Chronically under-funded, Florida’s system of care has left hundreds of state psychiatric patients in danger. And when violence followed, mental health administrators often cleaned up the mess, failed to report it quickly to law enforcement — and often looked the other way.

Records obtained by the Miami Herald show hospital administrators waited 17 hours before reporting the attack on Barrett to the Baker County Sheriff’s Office — time spent scrubbing the grisly crime scene and allowing Stone to dump his blood-soaked clothing in a hamper. Though the hospital told deputies they did not know Barrett had been assaulted, Barrett’s medical records clearly say otherwise.

Angela Barrett remembers getting the call from a Jacksonville doctor to report her father was brain dead. To this day, she said, neither the Department of Children and Families, which oversees state mental hospitals, nor hospital administrators ever explained to her exactly what happened — or apologized for her loss.

“I felt like I was in a horror movie. I was just in shock,” Barrett said. “I did not even know that [criminal defendants] were living at the facility.

“People are sent there for treatment and to get better, not to be victimized by criminals.”

A dangerous mix of patients

State mental hospitals accept residents from both civil and criminal courts. Under Florida’s involuntary commitment law, called the Baker Act, a person can be ordered into a state hospital for six-month intervals. Ideally, patients are stabilized and then released back to their communities for continuing treatment. Some patients require life-long hospitalization.

The state also operates what are called forensic hospitals – which accept criminal defendants who are either found not competent to stand trial, or not guilty by reason of insanity. Forensic hospitals are secure facilities ringed by razor wire, with trained officers, handcuffs and pepper spray. They’re designed to hold sometimes violent, repeat offenders.

Civil facilities generally lack such security, potentially leaving their residents in jeopardy, especially when an incident occurs and there is no staff capable of intervening.

After patient’s eyes ripped out, a scathing report on security at South Florida hospital

Under Florida law, DCF has 15 days following a judge’s order to accept custody of a forensic patient. But inadequate budgets and long wait lists have made that mostly impossible.

The solution, or at least one of them, has been to transfer dangerous criminal defendants into non-secure civil facilities to free up beds.

It is a cure that sometimes kills.

Stone, who was from Lake County in Central Florida, had been found not guilty by reason of insanity on an attempted murder charge in April 2002, and was originally dispatched to a forensic hospital. But because of the lack of beds, he was “stepped down” to Northeast Florida — a civil commitment facility that was not designed to house criminal defendants.

At the Baker County hospital, sometimes violent felons are blended in among elderly and frail patients like Barrett, who had previously lived in a unit for geriatric residents. A hospital administrator said in sworn testimony that the mixing of vulnerable and violent residents continues because it is cheaper than keeping them apart.

When someone like Barrett gets killed, it can also be cheaper for the state to try to mollify the bereaved with money than to fulfill its obligation to provide adequate beds in state forensic hospitals. As of this week, the wait list for forensic beds at state hospitals topped 400.

“It makes me very angry,” Angela Barrett told the Miami Herald. “He was the only father I had. He was better than a lot of people’s fathers that I hear about, even though he was mentally ill.”

State won’t release violence data

As it has on several occasions, Northeast Florida mopped up the blood and tidied up the mess, a practice that has infuriated detectives at the Baker County Sheriff’s Office.

In July 2023 sworn testimony, Northeast Florida’s chief of security, Anthony Dees, said that the facility experiences 10 to 15 incidents each week where one patient assaults another, or staff. The Miami Herald asked DCF for the number of reports of attacks by residents at the state’s six psychiatric facilities; the agency never responded. DCF also has yet to fulfill a request under Florida’s public records law for records of alleged abuse and neglect of hospital residents since 2019.

It was April 5, 2021, when Stone attacked Barrett at the Northeast Florida State Hospital in Macclenny. The beating left Barrett with broken ribs, a seven-inch-long “ragged” gash on his head, profound brain damage and a loss of blood so severe that his heart couldn’t pump oxygen.

It was a repeat of what had happened six months earlier to a man named Sean, who was brutally assaulted by another “stepped down” forensic patient. Sean had been hospitalized for what doctors believed was a traumatic brain injury that left him non-verbal, physically unstable and cognitively impaired. Markeith Loyd, Jr., the attacker, was the son of a convicted Orlando cop killer who had been found not guilty by reason of insanity on attempted carjacking charges.

Read More: Covering up a deadly attack in a state hospital

Sean, whose last name is being withheld at the request of his family, lingered four months before dying on Jan. 12, 2021. DCF insists COVID was the cause. His mother is equally adamant that he would have survived if not for the savage attack, combined with additional injuries sustained after the assault.

Last month, the state Bureau of Vital Statistics reissued Sean’s death certificate, upon the request of his mother. The cause of his death now is listed as pneumonia and complications of blunt trauma to his chest.

DCF refused to release records of an internal investigation into Warren Barrett’s death, citing patient confidentiality. Florida law allows for the release of such records when a vulnerable adult, such as an elder or disabled person, dies as the result of abuse or neglect. An agency lawyer, John Jackson, said DCF’s investigation “did not kick in” such a requirement — meaning DCF concluded no one was responsible for Barrett’s death – other than Stone, presumably.

The agency reached the same conclusion after Sean died — though one investigation concluded two high-ranking hospital administrators were at fault for failing to move Sean out of danger. That investigation was withdrawn, and no one at the hospital was held to account.

Administrators declined to discuss Barrett’s killing, as well, but did issue a short statement: “Our primary focus is ensuring that patients receive high-quality services at the state mental health treatment facilities, and we are deeply saddened by the death of Warren Barrett.”

‘The system failed him’

“The system failed him. They had no excuse,” said Dustin Williams of Barrett’s death. An advanced practice registered nurse, Williams had overseen Sean’s care, though not Barrett’s, and had repeatedly warned administrators that his patient was unsafe. For his outspokenness, he was retaliated against. He received $800,000 after filing a whistleblower suit.

“They would rather pay someone off than fix the problem and have accountability,” he said. “There’s absolutely zero accountability. The state is policing the state.”

Sean’s mother, who is not being named to protect the family’s privacy, said DCF lawyers promised her after the Sept. 22, 2020 attack that docile or vulnerable patients like her son would be protected from violent forensic patients at the hospital.

After Barrett was killed, she texted Roy Carr, DCF’s then-head of adult protection: “I’m pretty sure you may know this already. I was assured by [Northeast Florida’s lawyers] that there was a policy in place to separate violent patients after Sean was attacked…Obviously this was another fallacy being told to appease concerned family members and patients.”

She added: “Changes need to be made to protect the vulnerable residents of [Northeast Florida]. This, on top of what my son endured, is beyond reprehensible.”

Carr’s reply: “Yes ma’am. Painfully aware.”

Warren Barrett’s death “could have been prevented,” his daughter said, if DCF had kept its promise to Sean’s mother. “Both cases are sickening.”

A promising life derailed

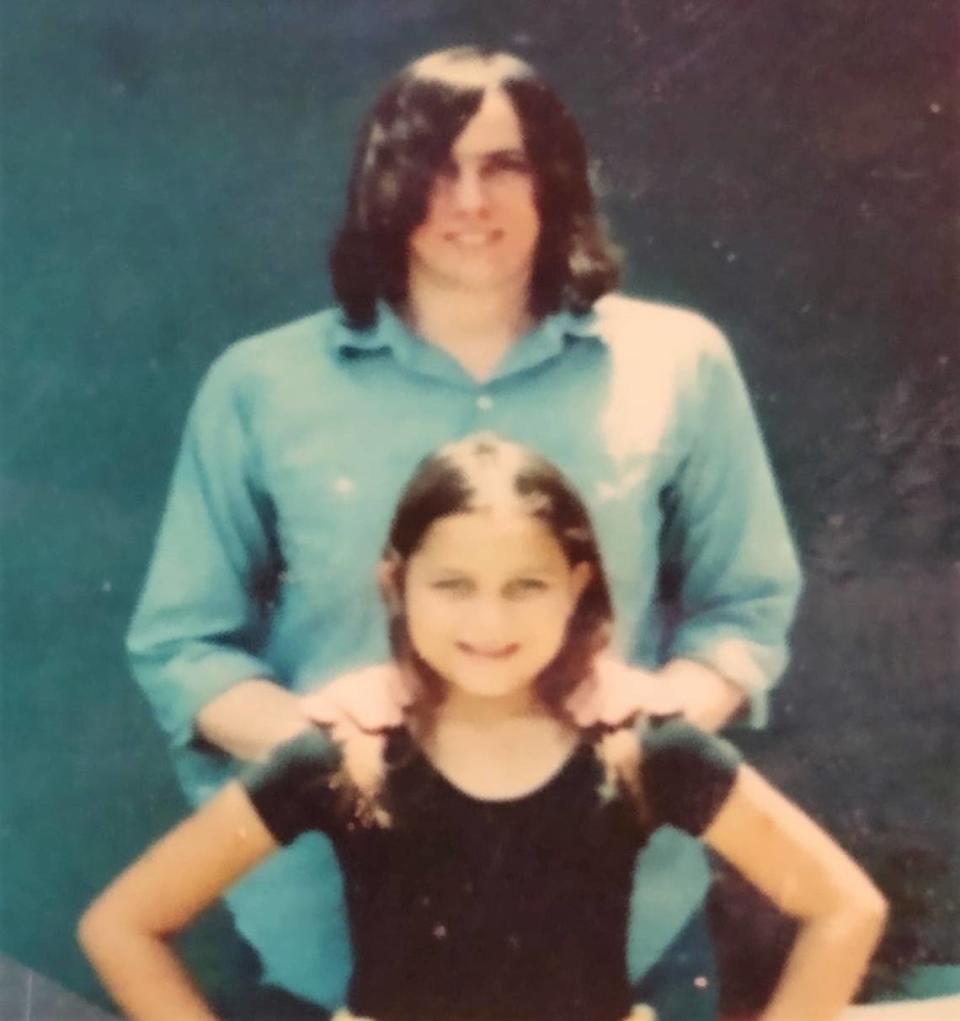

Little remains of Warren Barrett’s once-promising youth: there’s a black and white snapshot of him wearing a Hawaiian lei, and sporting a crew cut. And a color photo, probably a decade later, now with long, dark hair. He’s no longer the gap-tooth, big-eared kid of his childhood.

The other time-capsule relics include a news clipping announcing Barrett’s first place prize for Eastern Affairs in the Dade County Social Studies Senate Contest. A yellowed 1971 draft card. A birthday card for his mother, adorned with lavender, and yellow lilies. And his diploma from Coral Park High School, which his daughter keeps in a box in her closet.

Barrett — nicknamed Bud “because he liked picking flowers” for his mom — was a military brat, Angela Barrett said. His father fought in World War II and was deployed to naval bases before settling in the Westchester and Cutler Ridge areas and commanding a Coast Guard station on Key Biscayne. He and his brother – who served in the Air Force before becoming a NASA engineer – were both good students, she said.

He loved to read, especially World War II, military and history books. And he worked at the public library, stocking books and assisting customers. Some nights, Barrett and other “brainiacs” would meet up and discuss the Vietnam War.

Barrett had intended to go to college, like his brother, but his plans were crushed when his psychiatric symptoms emerged.

After he graduated high school in 1967, Barrett met his ex-wife through a friend, and they became parents when both were still teenagers, his daughter said. Barrett was exhibiting signs of mental illness by age 19. Angela Barrett said she was still a toddler when her father was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and her parents divorced.

“His parents took care of him,” Angela Barrett said. They rented an apartment for Barrett in Kendall, and saw to it that he got treatment. “They tried to give him a normal life,” she said. “They visited him regularly. They shopped for him.”

“Everybody was trying to do the best they could at the time, because he was diagnosed so young,” Angela Barrett said.

A family’s struggles to help

But Angela Barrett’s grandmother, who had earned income as a professional bridge player, eventually became gravely ill, and it became difficult for her to supervise her son, who had threatened, or attempted, to take his life often. He also exhibited strange behavior, once being detained after trying to hand out Tootsie Rolls to children at a nearby middle school.

Angela Barrett’s grandmother died in June of 2001, and Barrett moved her father into her home in Casselberry, an Orlando suburb, two years later. But, she said, she was raising two sons, including a 7-year-old, and her father’s presence in the home was chaotic. “They were young,” she said, “and wanted to have friends.”

Though her children loved her dad, Angela Barrett said, she took the advice of local police and had her father committed to a psychiatric hospital under the Baker Act. That was in 2005. Barrett toggled back and forth between hospitalization and community care until 2014, when he was admitted to Northeast Florida, where he remained until his death.

Barrett’s court-appointed guardian referred to him as a “hippie gentleman” in medical records.

“He enjoys rock ‘n roll, ‘70s bands, [growing] his hair long and Pink Floyd,” the guardian said.

Barrett’s illness was so severe that, both in young adulthood and later when he was committed to Northeast Florida, he underwent what’s called electroconvulsive therapy – formerly called “shock” treatment – to stanch his depression, his daughter said.

“His illness took a toll on him, mentally and physically,” said Angela Barrett, who sent her father books to read. The state returned them to her following her father’s death.

Though Barrett was reportedly a danger to himself, his guardian told a psychologist at U.F. Health in Jacksonville he was “unlikely to be aggressive.”

“A pool of blood”

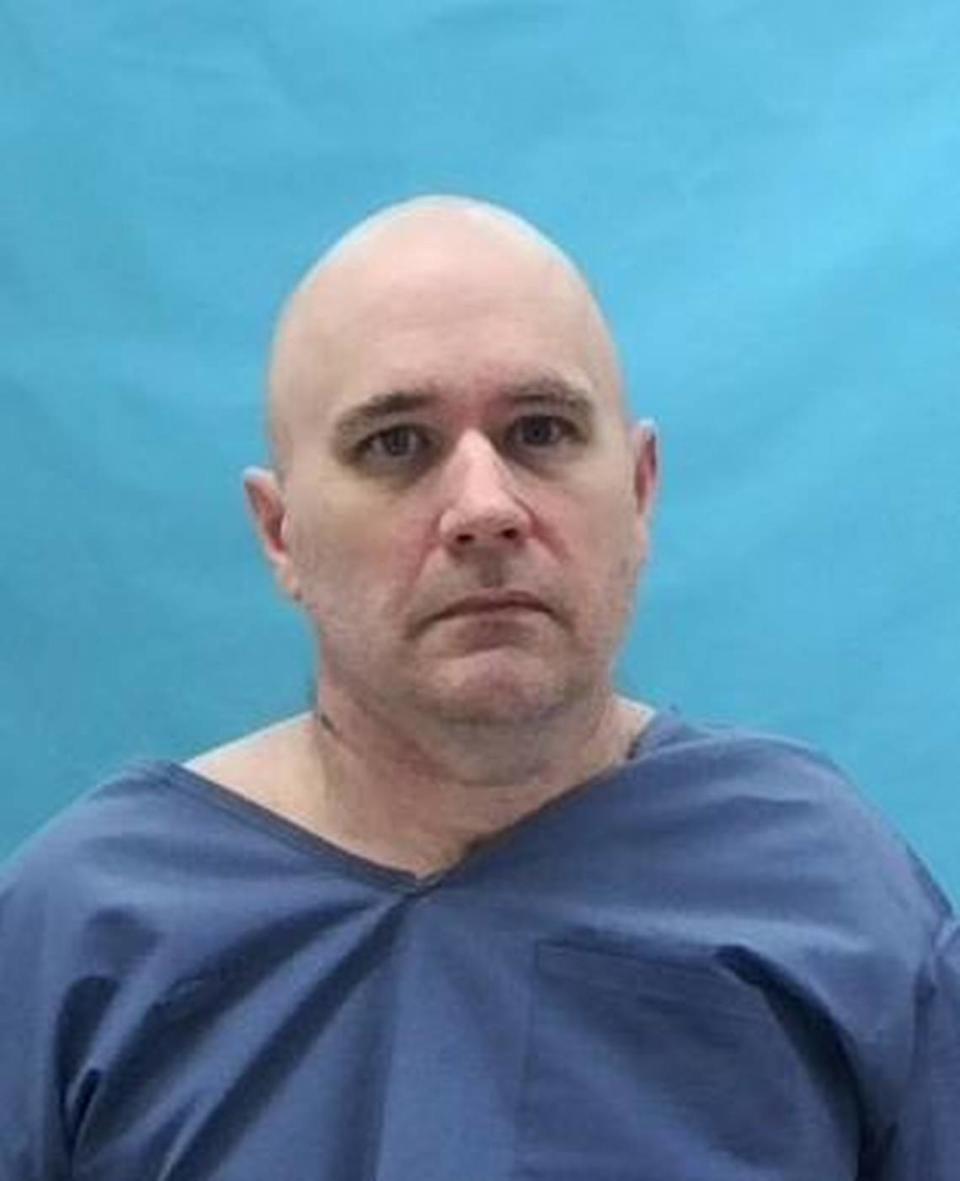

Mark Stone, listed in criminal records as 5-feet, 10-inches and 190 pounds, in contrast, had a well-documented history of aggression.

By September 1, 2001, the day Stone attacked his mother, he’d already been arrested 17 times, including charges for grand theft, auto theft, marijuana possession, driving under the influence, battery on a law enforcement officer, domestic battery and battery on a person 65 or older.

A Lake County Sheriff’s Office report said Stone’s mother, Sara Stone, had been found by deputies that day “lying face down on the floor in her home with her throat cut.” Before she was airlifted to the Orlando Regional Medical Center, she told a deputy “that her son Mark” did it.

About two hours after his mother was flown to the hospital, deputies found Stone in the woods near his mother’s home, draped in blood, the police report says.

The assault had occurred six days after a judge released him from his previous arrest – on a charge of battering an elder.

It appears that September 2001 prosecution – Stone was charged with attempted 2nd degree murder, as his mother survived the attack – marked the first time he was determined not guilty by reason of insanity. That’s when Stone was taken into DCF custody.

In the 20 years that followed, Stone cycled in and out of jails, state hospitals and community mental health centers. He added three new charges: cocaine possession, possession of drug equipment and a county ordinance violation.

It is unclear when hospital administrators transferred Stone from a secure, locked-down forensic hospital to Northeast Florida; DCF calls such transfers “step downs”. Stone was assigned to one of four beds in a room shared by Barrett, who, his daughter said, had recently been moved from a wing for geriatric patients.

On April 5, 2021, at a little past 1:30 a.m., a camera in Northeast Florida living area 58E captured Stone, dressed in khaki pants and a green polo, standing against a hallway wall. What had happened before that is redacted in a police report. Moments later, hospital workers entered the room, “and this is apparently when [Barrett] is found lying unresponsive on the floor,” police reported.

The bedroom where the attack occurred held four twin-sized beds in each corner of the room, along with four small dressers. The walls were made of concrete block, broken up by windows inlaid with “cage-like screening protecting the glass,” a report said. The floor was tiled.

The beating Barrett endured was so severe that both police and medical records describe finding him “in a pool of blood,” with reddish-brown blood stains on the wall behind him.

The list of Barrett’s injuries, as documented by a team of doctors at U.F. Health Jacksonville, was long and alarming: The nerve fibers in his brain had been violently sheared. Blood was collecting within his skull and on the surface of his brain. He suffered a seven-inch ragged laceration on his head.

17 hours to report attack

It took hospital administrators 17 hours to report the assault to the Baker County Sheriff’s Office. Hospital workers already had cleaned and mopped the crime scene. Stone had been allowed to change his blood-soaked clothing, which was later found in his hamper.

Detectives arrived at 5 p.m. As they walked through the crime scene, they found khakis and a polo matching what Stone wore in earlier video in a laundry basket next to his bed – “stained with dried blood,” a report said. Atop Stone’s bed was a yellow note pad, and in his dresser was a short note he’d written from the pad: “My own words. I could not just lay there and suffer bodily harm. I had to do what I could to prevent being struck.” He then asked for a lawyer.

When detectives interviewed Stone in a hallway, his right hand was swollen and bandaged. Detectives asked him how he hurt it. “A tooth,” he replied.

“On the walls and floor near the suspect’s bed I observed several reddish/brown stains that appeared to be dried blood,” Sheriff’s Captain David Mancini, Jr., wrote in his report. Hospital staff also gave detectives “bags full of blood-stained towels and sheets that came from the room after the incident occurred and when it was cleaned.”

When asked about the delay in reporting the assault, Mancini’s report says, hospital administrators said they waited because “the cause and severity of the victim’s injuries were unknown.” In a complaint about the hospital to state health regulators, Barrett’s daughter said she had been told hospital administrators initially thought the 72-year-old had fallen out of his bed.

A dubious explanation from hospital

The explanations are dubious, given the severity of Barrett’s injuries and the amount of spilled blood.

Barrett’s medical records cast further doubt on DCF’s explanations. UF Health, formerly Shands Hospital, records show that more than 15 hours before police were notified of the attack emergency medical workers who had airlifted Barrett told doctors Barrett was injured in an “assault”. Asked to describe the type of assault, doctors wrote: “beaten and punched”.

As well, a facial surgeon who treated Barrett wrote at 7:11 a.m. that day – 10 hours before detectives arrived at Northeast Florida – that he “was reportedly assaulted and found in a pool of blood,” medical records say. Notes from a neurosurgery consult two hours before detectives arrived also noted “multiple blows to the head,” and added: “He was beat by another patient.”

Detectives and supervisors at the Baker County Sheriff’s Office became so frustrated and angry with the hospital’s lack of cooperation that Mancini, the author of the report on Barrett’s attack, wrote an email to hospital administrators in May of 2022 threatening to “refer the [hospital] staff to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement” the next time his detectives were “called to an incident and the crime scene has been cleaned up.”

“It cannot be expected that any Sheriff’s Deputy be asked to respond to [Northeast Florida State Hospital] and conduct a criminal investigation with the facts, evidence, witnesses, or even the victims in some cases [being] altered, damaged, destroyed, concealed, manipulated, vanished, or dead when [hospital] personnel find it appropriate to report the crime to BCSO,” Mancini wrote.

Stone, 47, pleaded no contest to second-degree murder charges and was sentenced in February to serve 21 years in prison. He is incarcerated at Columbia Correctional Annex in Lake City.

Stone hand-wrote a rambling, mostly unpunctuated letter in February, asking his judge to grant him a trial or to release him to friends or family in Central Florida. He said he wanted to open a “dog grooming biz,” and owned a camper-trailer in which he could live.

Stone seemed to suggest he was not responsible for Barrett’s death, that someone else, whom he did not name, finished the job.

“I did just begin the process of bringing the man’s life to an end,” Stone wrote. He added: “Now, your honor, there is a whole new ball of wax whenever to polish off the existence of a human.”

The labor union that represents nurses at Northeast Florida was less concerned about the cover-ups than the assaults that preceded them. “A contingent of our members have contacted us regarding very serious security concerns they have for the patients and staff at Northeast Florida State Hospital.

“A significant number of ‘forensic’ patients…have been transferred to [the facility] and have been interspersed with the ‘civil’ patients. Such an integration of patients does not make for a secure environment,” John Berry, director of labor relations for the Florida Nurses Association, wrote in a April 26, 2022 letter.

A few months earlier, Berry wrote, two employees “were assaulted by a violent patient,” and were injured. “If other staff and patients had not intervened, the female nurse could have died.” Before that, another patient had “assaulted several other patients,” Berry wrote. Hospital workers asked for greater security, but “those recommendations were ignored.”

“Nobody will deny that working in a psychiatric facility is not an easy undertaking,” Berry wrote. He added: “Nobody should be forced to work every day thinking that they may be injured, disabled or worse due to management’s lack of concern for their well-being.”