Another record blob of sargassum measured in Central Atlantic Ocean. Will it reach Florida?

In the far off Central Atlantic, near where the Caribbean Sea meets the ocean, scientists are warning of a record amassing of unruly sargassum on a path guided by the whimsy of winds and currents and storms.

University of South Florida scientists said this week that the nearly 5 million metric tons of prickly pelagic fauna measured in December is far above the roughly 1 million metric tons recorded at the same time the previous year.

“Although we predicted an increase in the November bulletin, the magnitude of this growth is notable, with the December 2023 abundance representing a historical record,” USF researchers wrote in a Jan. 4 sargassum bloom forecast.

It is a similar message to what was announced last year, when the so-called Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt reached record proportions in the early months of 2023 with worldwide coverage of a potential coastal onslaught in Florida during premium summer tourism months.

The rabble of floating macroalgae eventually fell short of the 2022 record high of 22 million metric tons, plummeting unexpectedly by 15% in May — a decrease never observed since tracking began in 2011 and a signal of the capricious nature and lack of understanding of how the sea-faring biomass operates.

Still, USF oceanography professor Chuanmin Hu said the December tonnage “indicates that 2024 will be another major sargassum year.”

For now, the bulk of sargassum largely remains about 500 miles east of the Caribbean Sea. A substantial bloom, however, grew near the mouth of Venezuela’s Orinoco River in mid-December, moving northeast to harry Trinidad and Tobago with mats also breaching the southern Caribbean Sea, according to USF.

Is sargassum harmful?

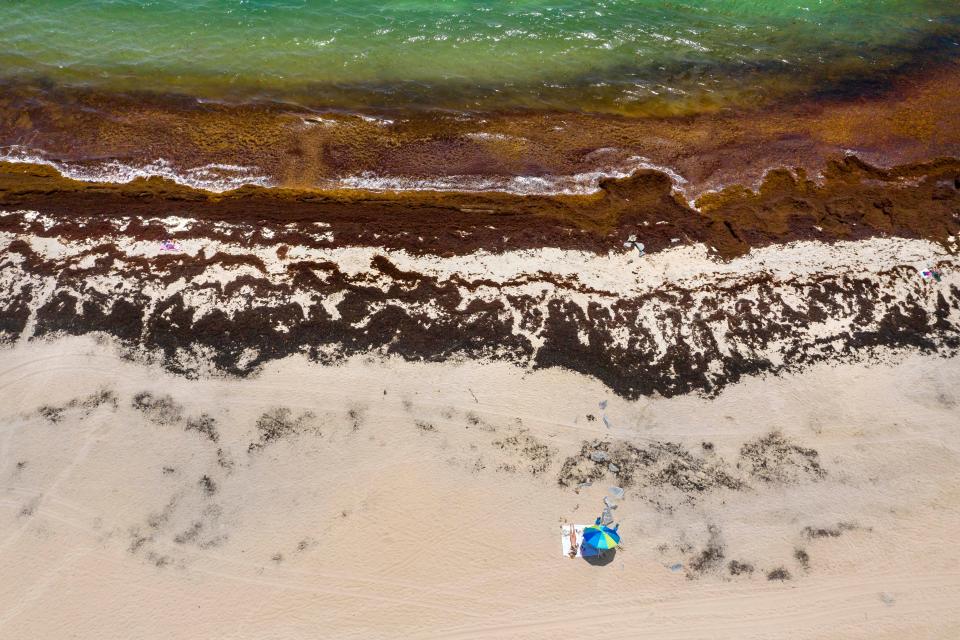

Sargassum is a lifeline for fish nurseries, hungry migratory birds and sea turtle hatchlings seeking shelter in its buoyant saltwater blooms. But in mass quantities, it chokes life from canals, clogs boat propellers and is a killjoy at the beach, piling up several feet deep like a rotting bog emitting hydrogen sulfide as it decomposes.

It's generally safe to swim in, but can turn the water an uninviting brown and be uncomfortable when it scratches against your skin.

“I’ve been in it to where it’s really hard to move through,” said surfer Cameron Koehler, an employee at Nomad Surf Shop near Briny Breezes on North Ocean Boulevard. “It can be super itchy, like a plastic feel with a bunch of little thorns.”

Koehler said customers don’t necessarily complain about the seaweed when it’s heavy on the beach or in the water, but do look for relief from rash guards or sun shirts.

“It’s definitely not a comfortable thing to be in,” Koehler said.

Is there sargassum in Florida?

It's too early to know how much seaweed will reach Florida's beaches, if any, but it has shown up in varying degrees and depths during every major growth year, hitching a ride on the loop current to assail the Keys and areas north from Miami to Jacksonville.

Hu's Optical Oceanography lab at USF measures the sargassum by satellite and has images dating back decades. He was part of a team of scientists that discovered the world's largest sargassum bloom in the Atlantic Ocean, dubbing it the Great Atlantic Sargassum belt.

Scientists began noticing the proliferation of sargassum in 2011.

Is climate change to blame for all the sargassum?

A 2020 report that included research by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration linked the proliferation of sargassum in the tropical Atlantic Ocean to a 2009-2010 change to the negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation, or NAO.

The negative phase of the jet-stream meddling NAO means a strong shift in winds to the west and south. Those winds flushed enough sargassum out of the Sargasso Sea to establish a colony in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. There, the sargassum got more sunshine and a high dose of nutrients from upwelling ocean waters, according to the report published in the journal Progress in Oceanography in March 2020.

"It's not clear if (the sargassum) is here to stay, but we don't yet see signs of it diminishing," said Rick Lumpkin, director of the physical oceanography division of the NOAA research lab in Miami. "It's possible that the 2009-2010 event happened before and that, after a few decades, the Sargassum belt died away."

Lumpkin said it's unknown if climate change led to the severe NAO shift in 2009-2010 but that humans help feed the sargassum bloom with higher nutrient discharges from rivers, such as the Amazon, where deforestation is occurring.

Higher rainfall amounts caused by a warmer climate can also mean more runoff from other rivers that exacerbate the bloom, including the Mississippi River and the Orinoco River in South America.

A University of Miami study released in 2019 found that smoke from African fires — either from those burning wild or burning to clear land — carried phosphorus that could fertilize the sargassum after it settles out of the atmosphere.

"There are definitely fluctuations from one year to the next, driven by changes in wind and nutrient runoff from the continents," Lumpkin said about sargassum amounts.

Last summer, the emergence of an El Niño climate pattern contributed to a weaker Bermuda High. That meant stronger and more consistent southwest and west winds, which helped push sargassum away from the coast.

El Niño is forecast to fade by June.

Kimberly Miller is a veteran journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Will record-breaking blob of sargassum reach Florida beaches in 2024?