Answer Man: Who were the first Hispanics in Western NC? Hint: think 500 years ago

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Today's burning question, in honor of Hispanic Heritage month, which runs from Sept. 15-Oct. 15, looks at who the first Spanish speaking people were to arrive in Western North Carolina. Got a question for Answer Man or Answer Woman? Email Executive Editor Karen Chávez at KChavez@citizentimes.com and your question could appear in an upcoming column.

Question: Hispanics are largely seen as late arrivers to Western North Carolina, coming in a recent wave of immigration. But when did the first Spanish-speakers get here?

Answer: Think 500 years ago. It's true, the biggest influx of people of Spanish or Latin American ancestry has come in the last few decades. But back in the 16th century there were some especially daring ― and by most historical accounts, destructive ― Spanish speakers who not only were the first Europeans to find their way to the Appalachians, historians and archeologists say, but were also the first nonnative people to build settlements in the North American interior. Some even made it the place where Asheville would be founded.

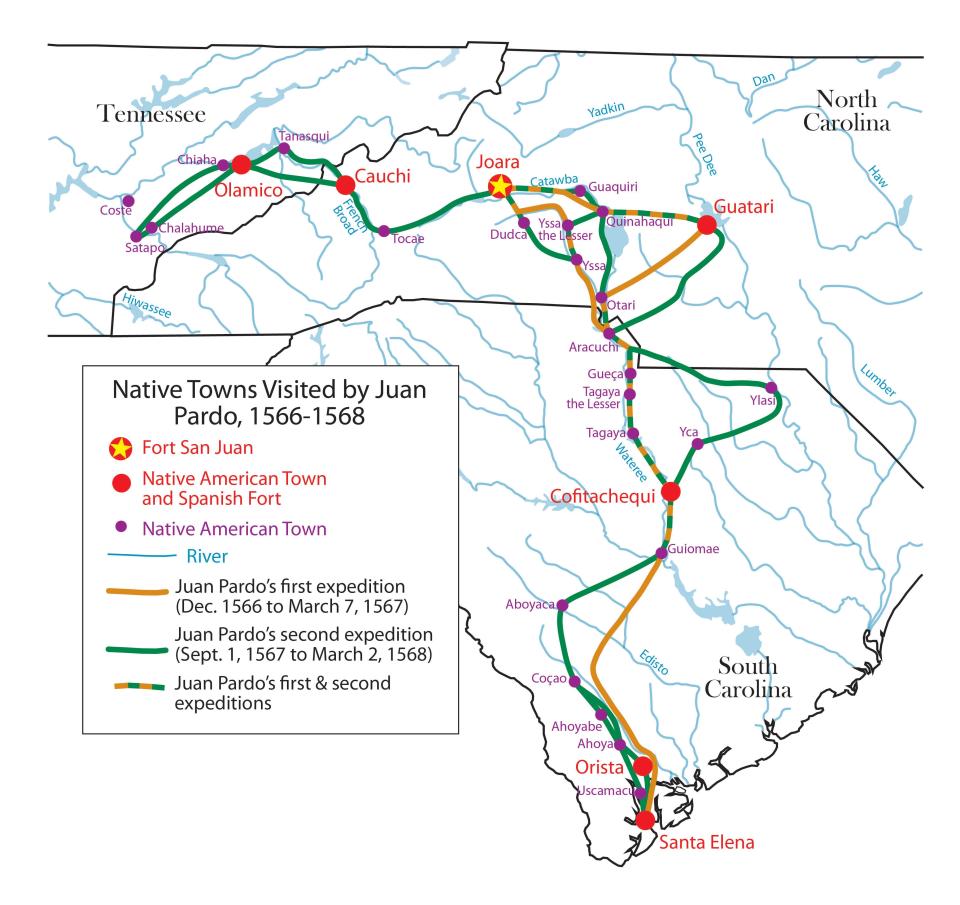

Normally, people think of the coastal areas of Florida and Spain as sites of early Spanish settlement. But two explorers, Hernando De Soto and Juan Pardo launched expeditions that reached the Southern Appalachians, then considered part of "La Florida," the vast area of the Southeast claimed by Spain and ranging from Louisiana to North Carolina. The goal of the "conquistadors" was to find sources of gold and silver and to secure routes for its transport to Spain.

I talked to University of Miami languages and literatures professor Viviana Díaz Balsera, who said an important part of the Hispanic legacy in the present day United States is these Spaniards being the first Europeans to make contact with many Native American peoples in the Southeast and their substantial documentation of the indigenous peoples they saw and interacted with.

“The Spaniards recorded their relationships with the natives, how they were received, how they traded with them, how much food was available. There's a lot of information in this documentation about the Native Americans in the region that help us to understand their politics and cultural sophistication," she said.

Díaz Balsera, a specialist in early Spanish culture centered around La Florida, said the documentation is not shy at showing the faults of the explorers, some of whom abused and mistreated the Native Americans.

De Soto, for example, was known for his cruelty against the indigenous people.

“But Juan Pardo was not,” Díaz Balsera said. “He was more of a diplomat. He did not want to create havoc with the indigenous people. He wanted things to go as smoothly as possible with them in order to secure their support.”

At least initially, many Native American leaders were open to contact, she said, looking to see how alliances with the Spaniards could benefit them politically and enhance their power in the area.

In 1540, De Soto's army ― along with Africans they enslaved ― became the first known nonnative people to travel through WNC. The Spanish had taken as hostage a female chief from what is now South Carolina to serve as a guide. But "the Lady of Cofitachequi," as she was called in written Spanish accounts, misled them toward the mountains and escaped.

The army traveled into a region inhabited by the Cherokee, accounts say. On May 29, 1541, they arrived at a place native people called Guaxle, which 200 years later would be the site for Asheville in the French Broad River Valley. De Soto pushed the army on, dying in 1542 in a Native American village on the banks of the Mississippi River after contracting a fever.

Pardo's expedition into WNC

A quarter century later, on Dec. 1, 1566, Pardo embarked on an expedition to try to claim the continental interior for Spain and map a route to Mexico's silver mines.

His smaller army followed many of the same trails, entering WNC at the start of January 1567. With the mountains covered in snow, the group stopped at Joara, the political, economic and ritual center of the ancestors of the Catawba tribe about 60 miles east of Asheville in present-day Burke County.

De Soto had also stopped in Joara, but moved on after obtaining food and supplies from inhabitants. Pardo, who gave gifts including metal knives to the tribe's leader, named Joara Mico, got permission to build Fort San Juan and a small settlement, Cuenca, adjacent to the town.

The fort's location ― not far from what is now Morganton ― was confirmed in 2013 after years of work by Warren Wilson professor David Moore and other archeologists who found enough evidence to definitively link it to Pardo.

UNC anthropology professor Rachel Briggs is co-director at the dig known as the Berry Site, where work continues to be focused on the fort as well as a structure believed to be associated with Joara and areas near a mound possibly built by the indigenous people.

"We have continued to recover Spanish artifacts from the site, and indeed, the concentration has increased in areas around the fort," Briggs said.

Pardo traveled from the fort after the winter, returning to St. Elena on the coast of Georgia. He left 30 soldiers, who later helped Joara warriors conquer a rival chiefdom near present-day Saltville, Virginia.

According to the expedition's official scribe, before leaving, Pardo “commanded ... that no one should dare bring any woman into the fort at night … under pain of being severely punished.” Despite this, an indigenous woman, Teresa Martín, later told officials that after “three or four moons,” the “soldiers caused disorders with the Indians and their women.”

Native men, potentially angered by this — as well as the soldiers' increasing demand for food — burned San Juan and five other nearby forts to the ground in the spring of 1568, killing all soldiers but Martín's husband, Juan Martín de Badajoz, who fled with her to Santa Elena. Juan Martín died in 1576 in a skirmish with native warriors.

Teresa Martín moved to St. Augustine, Florida, where in 1600 she testified about her experiences to a Spanish colonial governor, according to Western Carolina University Latinx Studies program director Melissa Birkhofer and her husband, Appalachian State University Spanish professor Paul Worley, who wrote about the indigenous woman who was likely born in Joara, but could have come from another tribe.

Birkhofer and Worley in 2022 found a "pay list" in University of Florida archives in which Martín claims her deceased husband's pay from the crown on the behalf of her daughter, Worley told me.

Many scholars say Chicano and Latino literature began with Spaniard Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca's writings about surviving a failed 1527 expedition in the Southwest and Mexico, Worley said.

He and Birkhofer are now writing a new piece in which they say rather than beginning with Cabeza de Vaca and the "European colonizers," scholars should look to multilingual and multiracial literatures "from the paylist and Martín's subsequent testimony."

"Our argument places the Berry Site, Morganton, and Southern Appalachia right in the center of things," he said.

More: Asheville City Schools 1st-graders learn beauty of Mexican heritage with cooking lesson

Lucia Ibarra, the 'Wetland Wanderer,' celebrates outdoors career, Hispanic Heritage Month

Joel Burgess has lived in WNC for more than 20 years, covering politics, government and other news. He's written award-winning stories on topics ranging from gerrymandering to police use of force. Got a tip? Contact Burgess at jburgess@citizentimes.com, 828-713-1095 or on Twitter @AVLreporter. Please help support this type of journalism with a subscription to the Citizen Times.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Who were first Hispanics in Western North Carolina?