‘Apocalyptic’: Scientists rush to rescue corals withering in Florida’s record-hot waters

An undersea rescue mission is underway in the Florida Keys.

Every day this week, boats, trucks and even a “coral bus” have arrived at the Keys Marine Laboratory in Long Key with precious cargo. Sloshing inside of coolers and wrapped in wet bubble wrap are thousands of fragments of corals that, until hours before, were growing in shallow nurseries managed by scientists.

They’re being raised as the next generation of corals for Florida’s dying reefs. But they’re in trouble.

This summer, the ocean has been way too hot, way too early. The record-breaking temperatures — including a mercury-popping 101-degree reading in a shallow basin on the Florida Bay side of the Keys that could challenge a world record — are cooking the corals alive. It’s not confined to cultivated corals in nurseries.

Weeks of hot, hot water has corals along Florida’s natural reef tract are spitting out the algae that they rely on for food and protection from the sun’s harsh rays. Their bone-white skeletons are stark signs of unhealthy corals. If the waters don’t cool, many might die — starving and sunburned.

“I think it’s shaping up to clearly be the worst bleaching event on record in the Florida Keys,” said Andrew Baker, who leads a climate change and coral reef lab at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science. “It’s as bad as it’s ever been and the prognosis is it’s going to get worse over the next few weeks.”

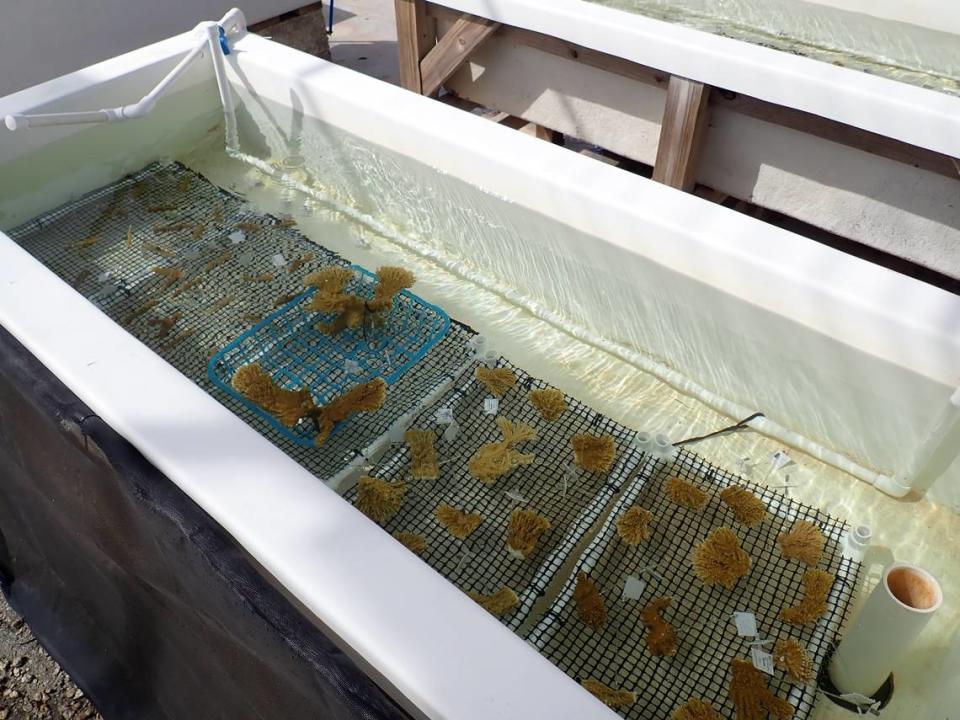

Dozens of scientists working to save Florida’s coral reefs are scrambling to save what they can, taking the highly unusual step of removing imperiled specimens and bringing them to the Keys Marine Laboratory operated by the University of South Florida and Florida Institute of Oceanography, one of several sites in Florida accepting refugee corals amid the marine heat wave ringing the state.

Cynthia Lewis, the lab’s director, said her team expected to reach 100% capacity for natural corals this week in all sixty of the saltwater aquarium tables they have on land. That’s about 5,000 corals, a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands still waiting in coral nurseries across South Florida.

“It’s an attempt to save a subset of what they have out there so they have something to rebuild with when the water gets cool again,” she said. “It’s an emergency rescue effort.”

‘More than a wake-up call’

It almost certainly won’t be enough to avert a looming and massive coral loss on Florida’s already struggling reefs.

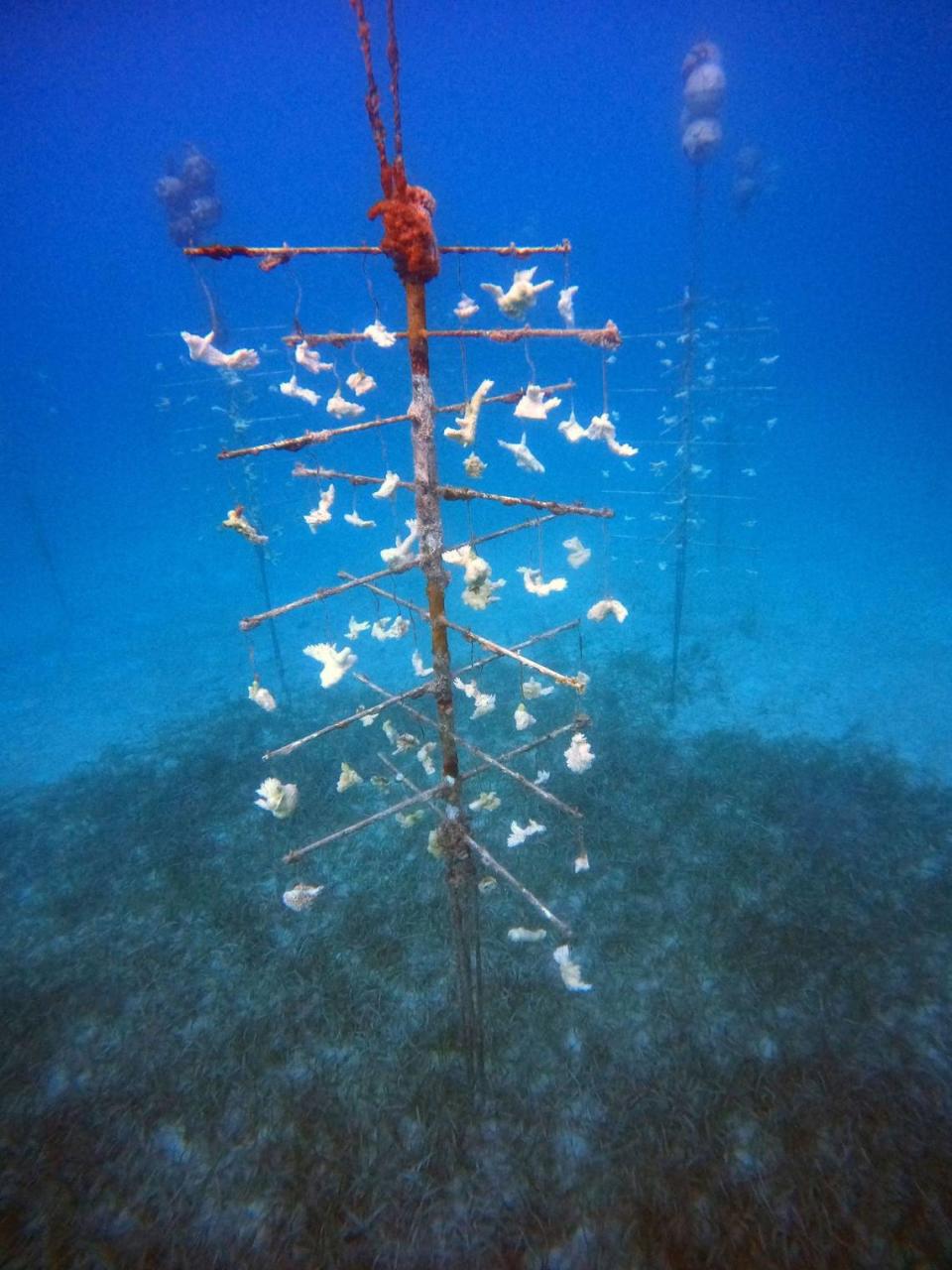

Some researchers have already reported “100% mortality” at their nurseries, including one in Looe Key run by the Coral Restoration Foundation. Photos show rows of metal trees covered in glowing white coral skeletons, five thousand of them, lost in a matter of weeks.

“This is an unprecedented, severe bleaching event, the result of a historic heat wave, too soon and soon fast,” said Phanor Montoya-Maya, restoration program manager at CRF. “We know that corals can recover from bleaching, but they’re dying too soon. This isn’t going to be your normal bleaching summer event.”

All of South Florida is currently under NOAA’s Alert Level 1 for coral bleaching, where bleaching is imminent. Though most of the significant reefs are on the Atlantic side, Florida Bay, where water temperatures have been highest, is under Alert Level 2, when severe coral mortality is expected.

By early September, all of South Florida is expected to be under Alert Level 2, NOAA’s highest level. Waters aren’t expected to cool down until October, at the earliest.

Conversations with coral scientists about the state of Florida’s reef system — and the risk posed by several more weeks of high temperatures — are studded with words like unprecedented, historic and apocalyptic.

One researcher put it more indelicately.

“It is just truly like holy sh--. It’s more than a wake-up call. What do you do when the house burns down? How do you rebuild without the pieces you need to start all over again?” said Colin Foord, a coral researcher and artist who founded Coral Morphologic.

Foord runs an underwater live stream featuring the corals in Port Miami, called Coral City Camera. But about two weeks ago, the elkhorns that made up the background of the normally lively and colorful scene started losing their color. Now they’re so white they reflect the moonlight in the late-night version of the stream, a ghostly presence in the black water.

Their deaths are all the more disappointing, considering that research helmed by Foord had recently shown that Biscayne Bay’s corals could be heartier than their Keys cousins — able to withstand hotter, dirtier and more polluted waters and still thrive.

In a warming ocean, some corals are winners. UM study has insights on heat tolerance

“Miami definitely has more bleaching-resistant corals, up to a point. Now we’re reaching that point,” he said.

On Wednesday, Foord dove into Biscayne Bay to scrape up a few of those corals that hadn’t totally bleached yet and deliver them to a land-based aquarium run by NOAA, a gene bank that preserves the genetic diversity of Florida’s corals so that one day in the future, they can be used to restart new life.

“Safely delivered to NOAA’s Ark,” Foord said in a text message late Wednesday, along with a photo of the still-brown corals bathed in blue aquarium light.

NOAA’s Ark

Scientists knew this was going to be bad weeks ago. Many stopped planting new corals altogether in late June, keeping them in aquariums rather than risk seeing the babies burn up in simmering ocean waters.

Montoya-Maya said his team is moving as many fragments as they can to the Keys Marine Laboratory, as well as to a Broward County nursery managed by Nova Southeastern University.

Researchers with the University of Miami also scooped up a few Biscayne Bay corals this week to transplant to an offshore nursery, where scientists hope the slightly cooler waters will revive them. At those same offshore nurseries, scientists have also lowered the metal trees filled with coral fragments to cooler, darker waters.

So far, most of the frantic action to protect Florida’s corals has been within the nurseries run by various university and non-profit research groups. There, coral is broken into chunks and strung up on underwater metal trees, where they quickly re-grow. An elkhorn coral, for instance, can grow from a finger-sized fragment to the size of a basketball in six to nine months.

These corals are easy to move, unlike their wild relatives that are cemented in place. For them, the only hope of rescue is getting selected to be part of the state’s ark project, a gene bank of diverse, wild specimens.

Scientists from the Coral Restoration Foundation set out to do just that in Sombrero Key earlier this month, but the heat beat them to it.

“When they got there it was too late. That genetic material has been lost to us forever,” said Alice Grainger, the foundation’s head of communications.

The foundation said it has the largest coral nursery in the world at one and a half acres. They produce more than 50,000 reef-ready corals a year, Grainger said. But it’s unclear how much of that will survive the coming months.

“We don’t know if we’re going to have to restart from scratch using the genetic material we’ve banked,” she said. “To rebuild production is a massive process.”

A generation lost

The last, and worst, coral bleaching event in Florida was in 2014. The state lost about a third of its elkhorn corals, one of the most common and most important reef builders in Florida. While it’s far too early to even guess at the death toll of this year’s marine heat wave, one important measuring stick of its devastation could come as soon as next week.

The first full moon of August usually marks a special time for Caribbean elkhorn and staghorn coral, the one time of the year they reproduce.

“There are grave concerns that with all the bleaching activities going on, these corals simply won’t spawn and we’ll lose a year’s worth of breeding,” said Baker, with the University of Miami.

Those two species of corals usually have two shots at reproducing in a year, early August and early September, which is set to be even hotter. But scientists like Baker are worried that the high heat could disrupt or even cancel either breeding attempt.

“It’s probably entirely possible they are not going to spawn,” said Foord. “If they don’t have the energy resources to have sex that year they gotta skip it, which is likely to happen.”

Scientists do have a backup plan in case that happens. The University of Miami is considering snagging a few corals and putting them in special tanks that mimic all the perfect spawning conditions, including moonrise and sunset times. They’ve successfully spawned elkhorn and staghorn coral in captivity before, but so far, only those two species.

That managed breeding program is one of the tools scientists across the state are preparing for a future that involves a lot more bleaching events and scorching summers.

Scientists want to rescue reefs and protect Miami with tougher breeds of staghorn coral

Researchers are studying a slew of solutions for Florida’s stressed-out corals, including moving them to healthier reefs, slathering them in probiotics, breeding heartier varieties and even editing their genes to genetically modify a coral that can survive far higher temperatures.

But Bakers’s favorite solution is one of the focuses of his lab. It involves breeding a heat-resistant version of the algae that symbiotically live inside the coral, the stuff that gets spit out when the coral overheats.

“That’s a really promising solution because that’s something we can already do now as part of our breeding attempts,” he said. “We believe it can make them one or even two degrees Celsius more heat tolerant.”

But ultimately, most coral scientists agree that all this new technology will only buy coral reefs a little bit of time. As the world continues to warm from unchecked, human-caused climate change, the oceans will continue to heat up and corals will continue to die.

Can hybrid super reefs defend the coasts? UM leading research for military project

“There’s no escaping the fact that, unfortunately, we have to address the root cause of it all — climate change,” said Baker. “At this rate of global warming, these ideas may only buy us a few decades of respite.”

“We’re going to have to have some time-buying methods in place so that if or when we get the climate warming under control we still have some corals left.”