Art so white: Black artists want representation (beyond slavery) in the Met, National Gallery

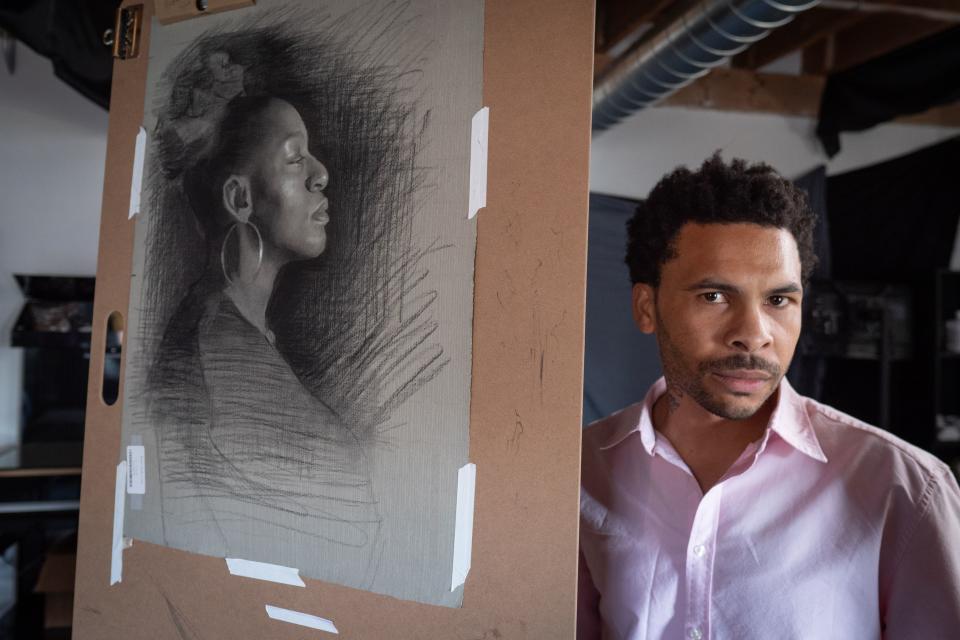

ATLANTA – A black female model leans on a stool atop a platform in a second-story studio in the city's historic arts district.

She is nude, stoic and motionless. A half-dozen students have formed a U-shape around her as they draw her, using charcoal pencils.

George Morton, the instructor who opened the Atelier South in January, stops by each student's workstation to offer a critique.

The model, Morton says, symbolizes what he believes is missing in fine art: the fair representation of black people.

Artists say African Americans are absent from historical art collections in some of the world's largest museums, galleries and major auctions. They insist that most of the paintings and portraits hanging on the walls of these institutions were created by white men and feature prominent white figures in American or European history.

Morton is part of a movement of black artists and curators from New York to Atlanta who are hosting exhibits, teaching classes and creating work that shines a light on black culture.

“We have been largely overlooked, historically,” said Morton, who graduated from the Florence Academy of Art US. “We weren’t seen fit as a worthy model, unless we were ... somehow an object that has been subjugated in a painting."

For example, the 1862 portrait "Men of Progress" by Christian Schussele shows 19 white, male American scientists and inventors but neglects the women and black inventors of the time.

And in Dutch painter Jan Verkolje’s 1674 portrait of Johan de la Faille, a black slave is at his side holding the hunting spaniels.

Getting the work on the walls

Directors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, two of the nation's largest museums, admit there is a disparity.

The Met has hosted eight exhibitions focused on African American artists in the past 10 years. The museum has about 40 exhibitions every year.

At the National Gallery of Art, there are 986 works by black artists out of the 153,621 total works.

The Met has made key acquisitions of black art in recent years, including the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift and a group of African American portrait photographs from the 1940s and 1950s. The two collections numbered more than 200 works.

Max Hollein, director of the Met, says he is working to diversify the collections and exhibitions at the museum. This may mean rewriting art history in a way that includes all cultures, Hollein says.

"To look back and look at what may have been overlooked, and what may have not been properly appreciated, what may have been misunderstood" is important, Hollein says.

Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, says the gallery has been working to diversify its portrait collections for the past decade. When Sajet joined the gallery in 2013, staff members decided that 50% of all money spent on art would support diverse artists and portrait subjects.

Sajet says white men dominated famous portraits because they owned land and art was historically reserved for the rich and elite.

Sajet says she wants the gallery to tell the story of ALL Americans.

"We owe it to Americans to reflect them because we owe it to accurate history," Sajet says. "I’m not interested in only having a museum for some people."

The National Portrait Gallery unveiled an exhibition last year called "UnSeen: Our Past in a New Light: Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar," using their work to show how people of color are missing from historical portraits and that their contributions to history were ignored.

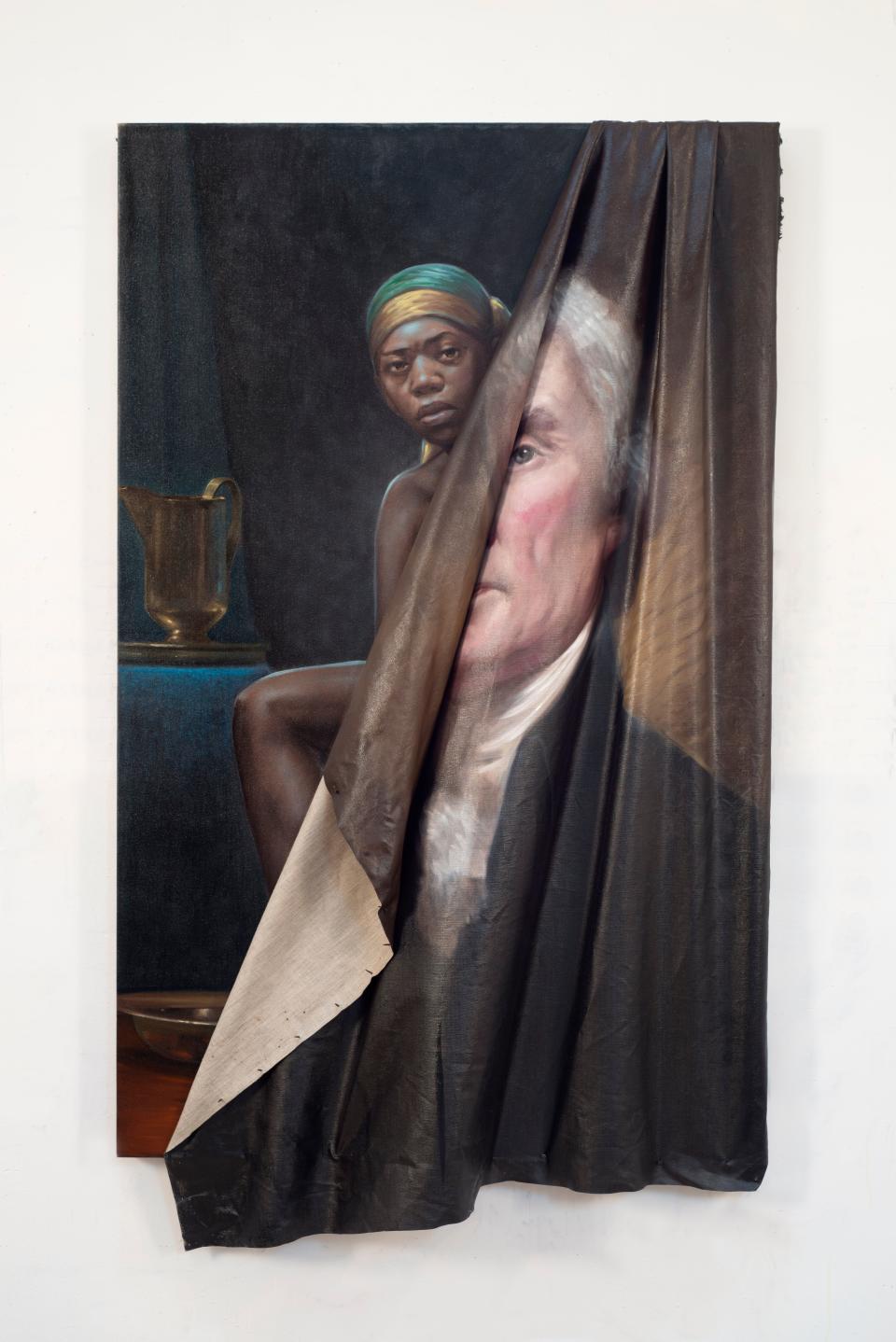

In Kaphar's "Behind the Myth of Benevolence," an iconic portrait of Thomas Jefferson is being peeled away from the canvas to reveal a portrait of an enslaved black woman.

Kaphar re-creates well-known historical paintings to include black subjects. His work sends a message that while people in power were glorified in art history, the powerless were sidelined, according to the Portrait Gallery.

New York-based visual artist Kehinde Wiley, who painted Barack Obama's presidential portrait, also takes young black men and places them in the historical poses from classical European paintings of noblemen, royalty and aristocrats. The paintings are meant to show black men in a position of power.

The Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) unveiled the exhibition “Mapping Black Identities" in February that showcases work by black artists who celebrate black identity.

Gabriel Ritter, curator and head of contemporary art at MIA, says the exhibition is meant to "dismantle a structure of white supremacy" that has defined the museum and many others for so long.

Ritter says he was adamant about selecting black art that demonstrates joy and pride, and not the narratives of pain and struggle that some museums display.

"It’s really about recognizing who the public is and who the audience is and making sure there is equitable representation,” Ritter says. “It can’t constantly perpetuate a white male stereotype of who is important in the art world."

The Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles is also boosting support for black artists.

Last year, the institute launched its African American Art History Initiative to collect archives and records. Previously, unless an artist was represented by a major museum or gallery, his or her historical record was not preserved, says Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute.

"I think that it's one of the really underrepresented stories in American art," Perchuk says. "And we really don’t have a full picture of American art without doing a better job of documenting the history of African American art."

The initiative will give museums the resources they need to host more exhibitions on African American artists, Perchuk says.

Artists such as Wiley, Kaphar and Kerry James Marshall of Chicago have their art on display at galleries across the country.

Last year, Marshall's painting "Past Times" sold at a New York auction for $21 million.

A post shared by Sotheby's (@sothebys) on May 13, 2018 at 10:59am PDT

Demands unmet

Jennifer Tosch, founder of Black Heritage Tours in New York and Amsterdam, says people of color have been excluded from the ranks of fine artists in America and viewed only as "objects of observation."

"You can certainly connect it to structural and institutional racism," Tosch says. “There’s been a systemic history of race and racism as its byproduct that has situated black people in a certain way."

It's not just black artists but patrons who push museums to change.

Black millennial travel groups and black baby boomers alike who have disposable income visit museums and request more of a "black experience" on their tours, Tosch says.

“There is an increase in black patrons of the art,” Tosch says. “They are exploring and looking for this representation and not seeing it.”

Michelle Obama's portrait by Amy Sherald remains popular at the National Portrait Gallery.

Opening doors

Morton is working to overcome disparities by selecting more people of color to be the subjects of live drawings in his art classes at Atelier South and engaging and training more black artists and young people in the majority-black city of Atlanta. Most of his students are white.

Black people, Morton says, have shied away from art because it was dominated by the white elite and wasn't considered a field where black families could make a living.

"When you look in the museums and don’t see yourself represented in the galleries ... it never even occurs to you that that’s even for you," Morton says. "There’s a message implanted in your mind that you don’t belong here.

"A lot of it has to do with those doors being closed for so long. And only now are we able to catch up.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Art so white: Black artists want representation (beyond slavery) in the Met, National Gallery