'You can get through the worst': School lets teens lead approach to suicide, sex assault

This story about social-emotional learning was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

TAOS, N.M. — Standing in front of 240 freshmen and 80 fellow seniors in her school's gymnasium, a slight 17-year-old with her hair in pigtail braids took a long, shuddering breath.

Her audience was still. The girl had just revealed that she'd spent most of her middle-school years feeling suicidal, had been hospitalized for her own protection and spent two years in therapy before finally telling her mother the cause of her deep depression and thoughts of self-harm: She'd been raped by a man she knew.

After two beats that felt like an eternity, the room exploded into supportive applause. The girl's face crumpled as friends rushed to her side.

"I felt like it was my fault," she said of the rape. "I felt like I provoked it." She said she'd learned through therapy and open communication with her parents that rape is never the victim’s fault and that thinking about suicide is not a sign of weakness.

"You can get through the worst thing and come back from it," the girl with the braids told the assembled freshmen, who sat in the orange and black bleachers facing a group of seniors seated on the basketball court. "I'm alive. I don't want to die anymore. I'm here. I'm OK. I'm living to the best of my abilities."

'Our kids are tired of education'

It was the third day of Taos High School's EQ, or emotional intelligence, retreat. Led by volunteers from the senior class, the retreat has become a spirit week tradition in this rural New Mexico county over the past eight years. The retreat, timed to coincide with a week of activities aimed at raising school pride, helps welcome freshmen to campus and assure them they are not alone in facing the challenge of their high school years.

The idea that schools might be responsible for addressing the mental and emotional health of their students has become mainstream over the past decade, said Jessica Hoffmann, a research scientist and the director of high school initiatives at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. Fourteen states, including Arkansas, Nevada and Tennessee, now have social-emotional learning goals for K-12 students. Still, most states, including New Mexico, don’t require schools to teach their students skills for handling their emotions.

Suicide prevention: Self-care tips, true stories on how survivors cope

More: We need to talk about suicide more

“It’s a culture shift to recognize that humans are emotional beings and emotions can be harnessed and channeled to improve academic performance and improve relationships and improve decision making,” Hoffman said.

Emotional and mental health, school climate and school culture were priority issues for educators, policymakers and students alike, according to a recent study by Child Trends, a research organization focused on issues affecting children. While teachers and policymakers were more focused on the effects of students’ family lives, students were twice as likely to mention school climate as an important part of their mental and emotional health.

Asked in a separate 2015 survey to describe how they felt in school, the words high school students used most frequently were “tired,” “stressed,” and “bored.” About 75 percent of the words students chose to describe how they felt at school were negative. The survey, which was administered to 22,000 high school students from around the country by researchers at Yale’s Center for Emotional Intelligence, also found that students who reported their peers had been mean or cruel expressed greater levels of loneliness, fear and hopelessness.

Related: NYC’s bold gamble: Spend big on students’ social and emotional needs to get academic gains

The EQ Retreat is Taos’ answer to the problem of too many students spending their school days feeling down.

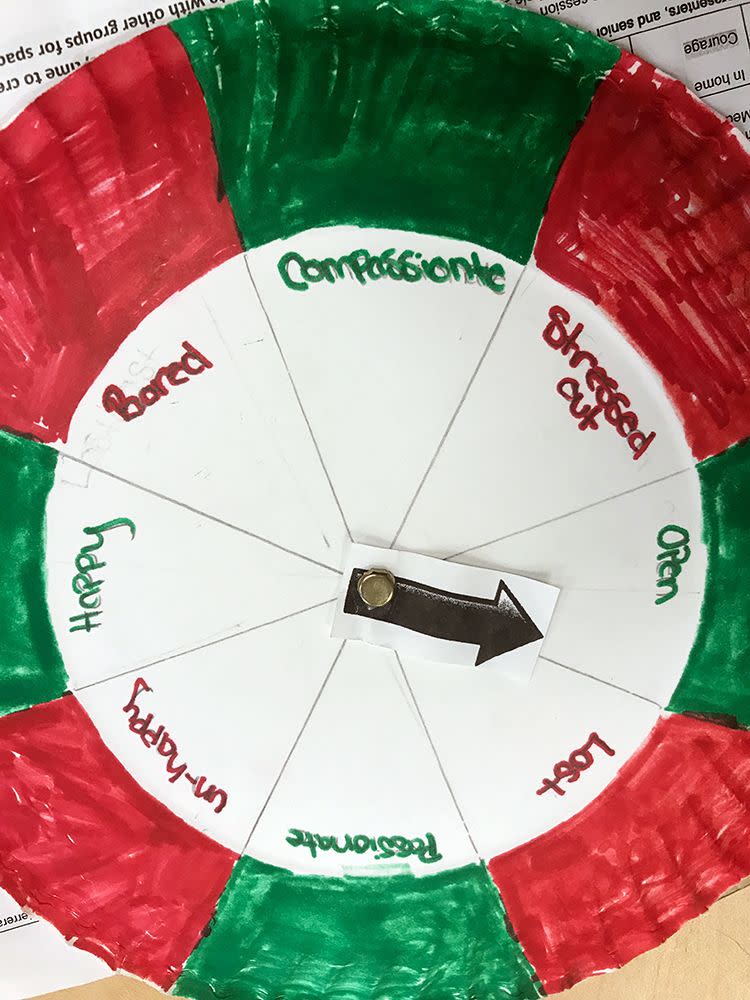

Teachers and community members lead sessions on dealing with grief through meditation, teach improv skills to help students learn to stay in the moment and walk students through activities meant to demonstrate how much they have in common. But the 17- and 18-year-old seniors occupy the starring role. They lead ice-breaker games, run an art project, share their own stories of struggle, encourage the freshmen to come to them with problems and make sure they learn the name of every younger student in their group.

“I wanted the freshmen to feel safe,” said Manuel Baca, another senior who shared a story. “I was just hoping to open up everything I had inside and share as much as I could, while at the same time as showing the freshmen that it’s OK to share.”

Having a student like Baca, who throws discus for Taos’ record-holding track team, act as a role model and get up in front of a few hundred kids to share his feelings is an event many school leaders would hardly dare hope for.

Ned Dougherty, the teacher-leader of the EQ retreat, says he is consistently impressed by his students and believes firmly that their best path forward is to depend on each other. “Peer-led social-emotional learning is the answer,” he said.

His role as a teacher, he added, is to give students time and space at school to both process their emotions and learn how to handle them.

“Our kids are tired of education,” said Dougherty, who teaches history. “Our kids don’t think adults see them as having a place in the world.”

He hopes the retreat will help change that for his rural students.

Known to outsiders as a resort town and artists’ retreat, Taos County is home to a mostly low-income population; 82.9 percent of the school district’s students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a federal measure of poverty. The high school’s top-notch sports program and its Advanced Placement courses help send a few students a year to prestigious out-of-state colleges. Yet, as in many New Mexico schools, few in the wider student body prove proficient on state tests of reading (34 percent) or math (10 percent).

Is the retreat a wise idea?

Not everyone at the school thinks holding a three-day retreat that highlights teenagers’ emotions is the best idea. Even some of the adults who are involved in running the retreat have concerns about some of the methods.

Victoria “Amani” Carroccio, a certified school counselor who works at Taos High School as a wellness coach, said teaching student skills to deal with trauma, grief and loss is a wonderful idea. But she also thinks traumatized teens should not be sharing their stories in a room full of people.

“Trauma is not healed by retelling the story,” Carroccio said a few weeks after the retreat.

Sexual assault, suicide and self-harm were three of the more traumatic topics raised by seniors, either in front of the entire freshman class at the morning session in the gym or in smaller group sessions with their assigned freshmen. Suicide came up more frequently at this year’s retreat than it has in years past, some said, which might be because it’s increasingly on young people’s minds.

Teens nationally were more likely to report feeling persistently sad and hopeless in 2017 than they had for 10 years, according to the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while most risk-taking behaviors have been on the decline since the mid-90s, the rate of suicide-related behaviors has risen in the last decade. In 2017, 17.2 percent of the 14,856 Youth Risk Behavior Survey respondents reported that they had “seriously considered suicide” in the past 12 months.

New Mexico, like other Mountain West states, has among the highest suicide rates in the country. For New Mexicans aged 10 to 24, the suicide rate is 50 percent higher than the national average, according to the state’s department of health. Deaths by suicide among young people in New Mexico are also sharply on the rise, having increased by 50 percent between 1999 and 2017. (The rate of teen suicide has also risen nationally since 2007.)

More: My mom took her life at the Grand Canyon -- and I wanted a why

More: Suicide rate up 33% in less than 20 years, yet funding lags behind other top killers

Given that the suicide of one young person can sometimes spur a second youth suicide, educators are often reluctant bring up the subject in school. However, the research shows that talking about suicide can actually help prevent additional deaths if the topic is not sensationalized and help is offered.

To start, experts now recommend suicide screenings as a routine part of schools’ mental health practice. Hearing from a fellow student who has been suicidal but found a way through those feelings can also be a great way to help teens who are suffering understand that they can get better, said Jonathan Singer, a member of the board of directors of the American Association of Suicidology.

Taos High School teachers do not vet seniors’ stories in advance. However, in conversations before the retreat teachers urged seniors to consider what wisdom they could offer the freshmen.

“Anyone could get up and tell them a story, but what do they need from you?” Dougherty said they asked seniors. The answer: “They need a way out of it. They need an action plan. They need hope.”

A few hours after telling her story, the girl with the braids said her primary goal had been to help others and that it was “a relief to get it off my chest. I keep on having people come up to me and hug me and tell me they’re there for me.”

Finally opening up to her mother had helped more than almost anything during her journey through depression, the girl said. She now believes that being open with problems is the best way to face them. “Any kind of backlash, good or bad, I don’t regret it,” she said. Nearly two months later, she said by email that she still felt better for having shared her story.

Taos High principal Robert V. Trujillo has been encouraged by what he sees as the retreat’s positive effect on school culture. He hopes that the school’s relatively new advisory period — a sort of extended homeroom— could provide the time to offer an emotional intelligence curriculum all year, to all students.

“Extracting days from academics can be very challenging,” Trujillo said. “But one doesn’t go without the other. If kids aren’t ready to learn because of the difficult emotional state they’re in, then (being in class) doesn’t help anyway.”

In 2016, in honor of its work to improve student wellbeing, Taos High School received a small monetary award from Yale and Facebook’s InspirED initiative. But the program’s origins and its current iteration are pretty homegrown — imagined first by students and nurtured over eight years by a series of overlapping teachers and community members willing to commit their time and expertise to the event.

Certainly, kids say, the program hasn’t fixed everything. With little prompting, a group of seniors started listing where each clique sat at lunch: The art kids go to Hensley’s class for lunch, the cool kids are in the lobby, jocks eat with their coaches, the band kids eat outside band room, the 4-H kids are at the outdoor tables …

But during the 2018 retreat, students said talking about hard topics was one way of caring for each other across traditional dividing lines.

"There's not enough discussion of hardship and trauma at high schools," said senior Leah Epstein. "To ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist doesn’t help at all."

If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) any time of day or night or chat online. Or text the Crisis Text Line for free, 24/7, confidential support via text message at 741741.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'You can get through the worst': School lets teens lead approach to suicide, sex assault