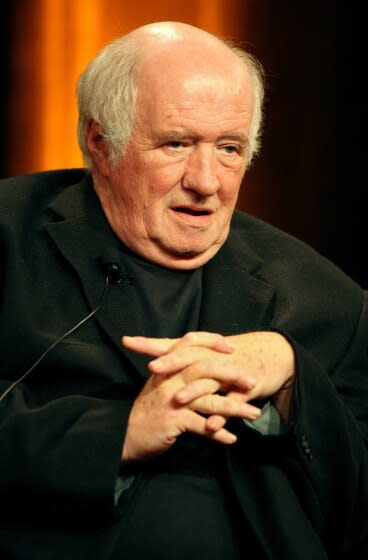

Appreciation: Art critic Dave Hickey was known for his blazing and cantankerous wit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Dave Hickey was a writer. He wrote short stories, fiction and journalism — essays about Liberace, the mechanics of zone defense on the playing field and what made loud, brash, vulgar Las Vegas America’s most American city.

Sometimes he wrote about music — country and rock ’n’ roll — and sometimes he wrote the songs themselves. And he wrote about art, which is how I got to know him in the 1980s.

Lots of smart people write smart things about art but nobody was a better writer than Dave. Hickey died Nov. 12 at home in Santa Fe, N.M., succumbing three weeks shy of his 83rd birthday after a long and difficult struggle with heart disease. He is survived by his wife, Libby Lumpkin, a feminist art historian and professor at the University of New Mexico, and a younger brother, Michael, of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. (A sister, Sarah Henderson, predeceased him.)

Two books published by Art Issues Press in Los Angeles stand at the top of his writing heap. “The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty” (1993), a slim, soft-cover chapbook, shook up an art world allergic to taking seriously the b-word, even though “beautiful” was a common exclamation in response to exhibitions of the most seemingly resistant conceptual art. “Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy” (1997), a collection of 23 columns gathered from the publisher’s monthly magazine, applied the dragon’s fearsome breath to culture both high and pop.

Still available, eight printings and tens of thousands of copies later, “Air Guitar” is easily the most widely read book of art criticism to appear in our time. Its lament resonates for art once seen as a disputatious civic forum, now overrun by the hard coin of investment markets. The democracy part of “Air Guitar,” which presciently foretells much of the political catastrophe in which we find ourselves today, is often overlooked.

Hickey’s smarts first got me interested in his work. My introduction was his essay in the 1982 catalog for “I Don't Want No Retrospective: The Works of Edward Ruscha,” a traveling exhibition from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His essay made paintings that I loved intelligible in plainspoken, even obvious ways that the critical baggage of High Art pretensions had hitherto obscured. The vernacular was good enough — for the artist and the art critic.

But it was the music in his writing that kept me going. Hickey, a brilliant and cantankerous wit, wrote for the ear. His work needed reading, not scanning, and rewarded effort with pleasure.

He was conversant with arcane philosophical treatises (his abandoned 1967 PhD dissertation in linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin involved critiques of Jacques Derrida and French structuralism). But, with all due respect, he found the iconoclastic concision of Waylon Jennings’ outlaw lyrics and the post-doo-wop drive of George Clinton and the Parliament-Funkadelic collective more effective than the hothouse theory flourishing in academic journals.

He had learned to love painting from his otherwise distant mom, Helen, a businesswoman and amateur artist, and he inhaled the intricacies of music from his jazz-musician dad, David, a car salesman who tragically died by his own hand when Hickey was 11. If art was to be seen, then writing, like a song, was to be heard. No wonder he could illuminate the work of Ruscha — an artist of painted language, overheard.

Hickey could be explaining the soft sensuality and exotic drift of his childhood move as a kid from Texas (he was born in Fort Worth), transported with family for a year to the beach in Los Angeles, and interject into his writing the wonder of a landscape dotted with “coco palms.” Those are tropical trees, of course, not imports found at the Southern California seashore. But if the tale needed to convey the bewildered bemusement of youthful dislocation, plus the sonic engine of a silly rat-a-tat given by a hard-c repetition to move things along, so be it. Coco palms in Pacific Palisades it was.

Half a dozen years passed after reading the Ruscha essay before I met him. Invited to speak on a panel in Texas, I accepted only because Hickey was scheduled as a local panelist.

By then I was filling in the back story. Since the late 1960s, he’d run A Clean Well-Lighted Place, a short-lived but legendary Austin art gallery; moved to New York and been director at Soho’s pioneering Reese Palley Gallery; become executive editor of Art in America, where he also wrote; done a stint writing and promoting music in Nashville; written for Rolling Stone and the Village Voice (“He’s as good as it gets, starting with his prose,” in the words of estimable Voice rock critic Robert Christgau); and, somewhere along the way, burned out on amphetamines and gone back home to live with Mom in Fort Worth to clean out. (He replaced speed’s high-wattage push with a white-knuckle cocktail of nonstop nicotine and caffeine.) The Texas panel remains hazy to me — was it Houston? Dallas? — but the boisterous showmanship of his riveting insight was clearly part of Dave’s reemergence from self-imposed isolation.

When I got back to L.A., coincidence happened: Gary Kornblau, whom I knew in passing from his occasional front-desk duty at Margo Leavin Gallery in West Hollywood, asked if he could bounce an idea off me for a magazine from art-rich, criticism-poor Southern California. Sure, I said — and there’s this guy in Texas you should publish.

The fit between Hickey as writer and Kornblau as editor at Art Issues proved to be ideal — which is not to say easy. A deadline for Dave was an excellent excuse to procrastinate, only to rev up to hyper-speed at (or after) the last minute and then, in editorial consultation, to hone the essay’s music.

The “Dragon” chapbook emerged as an intellectually ambitious statement of the critic’s working philosophy. The timing could not have been more volatile. The roaring, Reaganite 1980s marketplace having collapsed into deep recession, identity politics had moved into the art-world foreground. The institutional bureaucracies of museums and art schools that had grown up with it gathered the politics into a tight embrace. That was fine with Dave — with one big caveat. A work of art, he argued, does not represent a monolithic community.

Instead, he insisted, the best art creates diverse community — a free and open kinship of people attracted to it, now and in the future. That shared attraction among dissimilar but engaged participants was the “beauty” part. Beauty was an expression of variegated desires, not a thing.

To those not paying attention, Hickey’s claim was received as an anachronistic, reactionary affront. The mistaken assumption was that beauty was being advanced as an essential characteristic held within certain identifiable objects — what was known in the hoary past as “the beautiful,” a marker of aristocratic taste enforced by privileged elites. The error was even hoisted aloft in an inept UCLA symposium sarcastically, if revealingly, titled “On the Ugly.”

“Air Guitar” was the collection that spoke most eloquently of Hickey’s move to Las Vegas, where he assumed a teaching post at the University of Nevada (together with visiting professorships at Harvard University and L.A.’s Otis College of Art and Design). He began construction of something unprecedented — a small but lively local community of artists and art participants.

He had seen an opening. Las Vegas, he wrote, was a town blessedly “bereft of dead white walls, gray wool carpets, Ficus plants and Barcelona chairs,” the establishment furniture of an establishment art world that was colonizing every global continent. Somehow, the dull conformity had missed a flashy desert watering hole “where there is everything to see and not a single pretentious object demanding to be scrutinized.”

For authentic art, the city’s Ur-object defining a sense of possibility and wonder was the world’s biggest rhinestone, proudly displayed at the Liberace Museum.

When the friendly people at Chicago’s John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation asked me to quietly nominate someone for the 2001 installment of their annual “genius grant,” a millennium candidate was obvious. Hickey was the closest thing to that vanishing breed — a public intellectual — that America’s vain world of visual art could claim. I wrote an absurdly long but successful recommendation, emphasizing that the grant would reflect magnificently on the foundation, not the recipient, since everyone already knew he was a genius.

Following the MacArthur accolade, he proceeded to deposit most of the half-million-dollar prize into video poker machines on and off the Strip. The virtuoso artist Robert Irwin could move to Vegas in the 1980s and become an accomplished professional gambler to support himself, since the splendid art he made could not. Dave, however, had writing to earn his keep. As a punter dedicated to amateur standing, he knew the house would always win, but he wanted to know the game.

The game is over now, although we have at least one more Hickey rumination to look forward to. Libby Lumpkin told me that, over the summer, Dave finished a lengthy piece on Michael Heizer, the reclusive Nevada sculptor who has spent the last 50 years building a colossal fortress of mud and concrete called “City” in the midst of a harsh desert-nowhere. I imagine beauty is involved, and I can’t wait to read it.

Hickey will be buried Nov. 30, at 1 p.m., at Rosario Cemetery in Santa Fe. Everyone is welcome.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.