Appreciation: For all her hedonistic L.A. delight, Eve Babitz mattered because she was so serious

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s difficult to imagine now, perhaps, but there was a time when Los Angeles was hard to take seriously. I don’t mean for those of us who live here: I mean for those on the outside, those for whom “L.A.” meant a plastic place and a plastic people, with no culture and no soul. These clichés were insistent when I was growing up; they have never held much water, but in the late days of the 20th century this was what many people believed.

Eve Babitz, the great writer who left us last week, knew they did. She subtitled her first novel, “Eve’s Hollywood,” “A Confessional L.A. Novel” (“confessional” of what? Why should she have to tell us it’s an “L.A.” novel?) before kicking it off with a facetious comparison of herself to James Joyce and then an eight-page dedication canvassing rock stars, restaurants, foodstuffs, colors, like an Oscar winner gone berserk in her acceptance speech, like she wanted to be sure we knew that she knew this place was ridiculous.

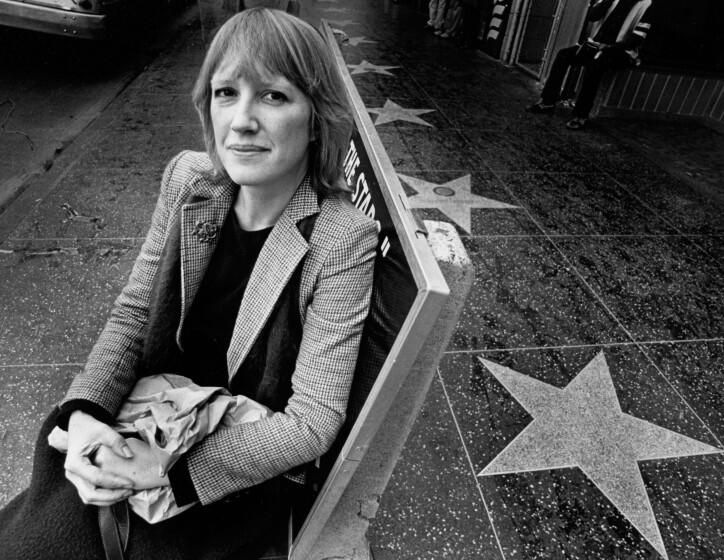

Eve Babitz. We might as well address the fact Eve played up that ridiculousness her entire life, that she was well aware of both her own frivolity and that of the Hollywood she inhabited. The 2015 reissue of “Eve’s Hollywood” shows her in a boa and bustier, the kind of carnal power move it’s hard to imagine, say, Joan Didion making for her author photo, while the titles of later books — "Sex and Rage,” “L.A. Woman" — toy with similar iconography. This place was her playground, emphasis on "play." So why should we remember her seriously? Why does she get to stand, as I believe she does, in the pantheon of important writers?

Unlike other fabled chroniclers of L.A. — or rather, of Hollywood, since that distinction matters in this case — Babitz was born here. Unlike Didion, unlike Raymond Chandler and Nathanael West, Babitz grew up on Cheremoya Avenue. You wouldn’t think that matters, as a great writer is a great writer and L.A.’s soil is fertile enough to nourish all kinds of transplants, but it does. She understood this place from the inside out, and moreover, she loved it without apology.

This took a kind of courage. (Do you think any of those writers, or any serious writer, was willing to embrace L.A. so wholeheartedly? William Faulkner called it “too large, too loud, and usually banal in concept.”) But it wasn’t this kind of courage, which she Trojan Horsed into her work by way of her sex kitten-ish image, that makes her work important, but rather another kind, which carried sharp insights into the broader condition of being (briefly) alive.

Open any book of hers almost at random and you’ll likely find something. A passage in “Eve’s Hollywood” describes the elation of hearing a favorite song as “like booster shots,” because “they make you stronger” — we all know that feeling — and then swerves: “You know it’s worth the twinge of envy when you’ve recovered from the dazzle because the mystery of life fades when death, people having fun without you, is forgotten. Time escapes unnoticed and time is all you get.”

People having fun without you. Such a Babitzian way of imagining death. But whether or not we’re all having as much fun without Eve as she would like (probably not), I can’t help but wonder that her real theme was time. Like any great writer, she understood that the only thing worth contemplating was death, that everything that stands between us and the grave needs to be written down lest it disappear without being registered at all, and that the only way to contemplate time is to contemplate place, which she did with everything she had.

Of the same Los Angeles wind that Chandler and Didion described in terms that were murderous, she wrote, “The Santa Anas were blowing so hard that searchlights were the only things in the sky that were straight.” Of Dodger Stadium, she described “the grass all mowed in patterns like Japanese sand gardens and the dirt all sculpted in swirling bas-relief.” Of Ports, her most beloved Hollywood restaurant, which closed in 1992, she notes a brand of mineral water “served in brandy snifters with lots of ice and a slice of lime.” Her writing overflows with local detail that veers into elaborate metaphor (Ports also “had the atmosphere of a colonial outpost,” where its rainy-day crowds were “crammed together like the subway at 5:15”), and it saturates throughout with both erotic and narcotic languor. Every writer who has ever described the pleasure of this place owes her a debt beyond imagining. Without her, we might still be thinking of L.A. as Faulkner did.

And yet, behind all this erotic joy (and Eve’s work is way less explicit than, say, “Ulysses,” if we’re keeping track of who gets to write about sex without being shamed for it) is that relentless gaze at mortality. It’s no accident that “Slow Days, Fast Company” (her best book; if you’ve never read Babitz, start there) opens not with a Quaalude haze or a late night at the Chateau but with a riff on Forest Lawn cemetery. That book may be the quintessential chronicle of L.A. hedonism, but it knows from the start exactly where it’s going. Where we are all going.

I didn’t have the pleasure of knowing Eve, really — I came to her work relatively late, and we communicated mostly through her sister — but I do know that later in her life she became a very private person. It’s a privacy that feels worth honoring even now, especially now, because her work was always in danger of being subsumed by a glamorous public image. Read it now, because time is all we get, because it’s something you should do before everything else she described — the desert oases of Palm Springs and Bakersfield; Emerald Bay; the old bones of the Garden of Allah; the houses of Bunker Hill — all disappears. And before you do too.

Specktor is the author, most recently, of "Always Crashing in the Same Car: On Art, Crisis, and Los Angeles, California."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.