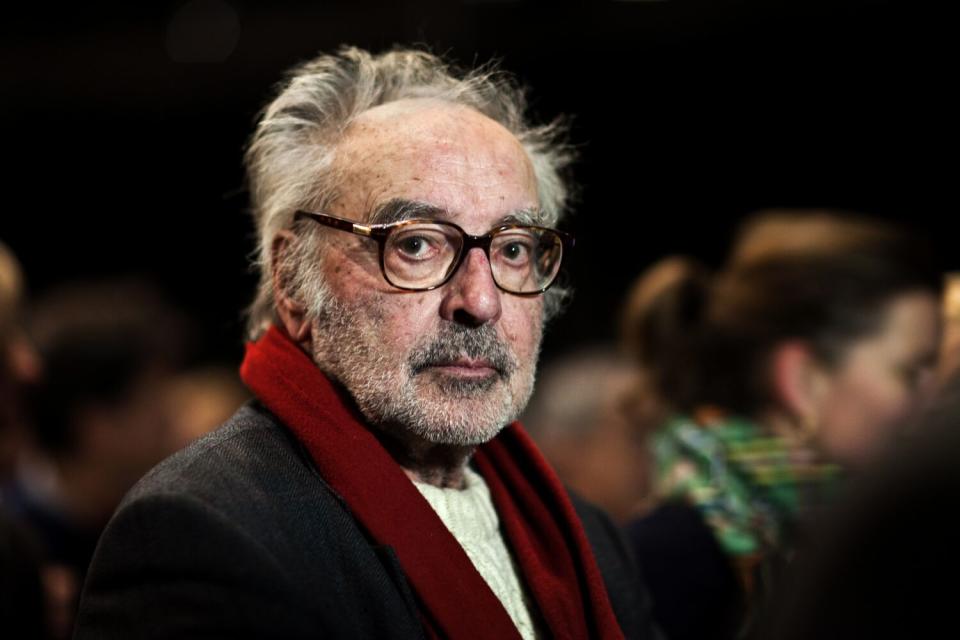

Appreciation: Jean-Luc Godard, a master of cinema who changed the medium forever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Of all the endlessly quotable maxims and aphorisms that have poured from the mouth and the movies of Jean-Luc Godard — “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun,” “The cinema is truth at 24 frames per second,” “A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order” — one that especially springs to mind today is this: “He who jumps into the void owes no explanation to those who stand and watch.”

It seems fitting to consider those words this week, and the void as well. Godard, filmmaker, critic, essayist, polemicist, crank, disruptor, legend and one of the most significant artists working in any medium over the last century, is gone today at age 91, having died by assisted suicide at his home in Rolle, Switzerland. The motion-picture medium that he studied, worshiped, mastered, mocked, deconstructed and sparred with for decades feels immediately and infinitely poorer for it. Does it feel, even, like the “end of cinema,” to quote the kicker of his 1967 apocalyptic freakout, “Week-end”? I hope not, but it’s hard to think for even a moment about what Godard means to cinema, an art form he revolutionized like no other, and not feel that something has permanently shifted.

The loss is incalculable. The tributes will be as voluminous and scholarly as his output, and they will mark not the end of a collective remembrance but a beginning. The practice of honoring our artistic giants is one that thrives on analysis, though speaking as someone who’s less of a scholar than a lay admirer of Godard’s work, I don’t feel particularly big on explanations myself right now. What feels more fitting to offer at this still-early moment of reckoning is a cluster of observations, associations and persistent memories from a moviegoing life that this towering artist and fearless iconoclast has long enriched.

From the moment he burst onto the world cinema stage, Godard operated with both a cool, insouciant defiance of cinema’s entrenched rules and traditions and a refusal to unpack his meanings for easy consumption. Then again, with a first feature as heady as “Breathless,” little explanation was really needed. Audiences stumbling out of a theater in 1960 may not have grasped the full significance of what they had just seen, but the movie’s playfulness and audacity swept them right up along with it. Hurling Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg into a lovers-on-the-run crime plot that couldn’t have been more beside the point, it was comic and tragic, dizzying and desultory, scrappy and fully formed, America and Paris, a jolt and a masterpiece. Above all, it was the work of a filmmaker who knew and loved the beats of classical cinema so deeply that there was nothing left to do, really, but throw them out the window and start fresh.

Over the first seven years of his career, which planted him at the forefront of the French New Wave and the height of his international cine-celebrity stardom, Godard cranked out an astonishing run of 15 features. From “Breathless” to “Week-end” (1967), they remain nonpareil in their stylistic invention and energy, their mix of scruffy dynamism and impossible glamour. Watching them — and they hold up beautifully — you can all but feel a medium racing to keep pace with a culturally and politically tumultuous moment that was shifting and fragmenting more quickly than anyone, save perhaps Godard, could take stock of.

Many of his best-loved movies arose from this ’60s heyday, and they connected and endured with audiences, in part because their irreverent play with the medium was so clearly a form of love. “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders” (1964) were romantic gangster movies in much the same oblique way that “A Woman Is a Woman” (1961) was a musical or “Alphaville” (1965) was a piece of science fiction. They treated genre as a beloved and well-worn toy, something to be played with for a little and eventually cast aside in favor of something more interesting. In doing so, they broke right through the seamlessness and artifice, the illusion of coherence, that audiences had come to expect from movies. Godard’s movies knew they were movies and saw no point in pretending otherwise.

Unleashing a wild panoply of film techniques — jump cuts, reams of text, eye-popping primary colors (but also jazzy black-and-white), verbal and visual nonsequiturs, startling disjunctions between sound and image — Godard liberated the medium from its prior allegiances to older art forms like literature and theater. At the same time, he exuded a magpie’s delight in sending cinema into collision with every other arena of the moment. He mashed up pop and classical music and drew graphic influence from glossy ads and movie posters. He took a pickaxe to every critical and commercial assumption about what movies could and should be, broke them wide open and reassembled the fragments into something radically strange and new.

To appreciate his work aesthetically requires a willingness to see — or to learn to see — the beauty in all this rupture and fragmentation, in states of confusion and sometimes maddening incoherence. To confront them intellectually is to wrestle with subjects that range from the pitfalls of consumerism and mass culture, subjects he critiques with elegance and feeling in “Masculin Féminin” (1965), to the temptations and contradictions that ensnare the characters in “La Chinoise” (1967), his alternately satirical and tender portrait of young Maoist radicals. It means contending with his dismissals of Steven Spielberg and Hollywood in “In Praise of Love” (2001), the beautiful and bilious work that heralded, for many, a major artistic comeback, and also to appreciate his despair over anti-Arab violence and conflict in both “Notre Musique” (2004) and “The Image Book” (2018), his last released feature.

But to overemphasize the challenge of Godard — quite apart from ignoring the fact that difficulty can be, in itself, something quite pleasurable — is to risk understating the sheer beauty and, at times, the tenderness of his work. Movie lovers have long enshrined the images of Anna Karina, Godard’s former wife and longtime muse, racing through the Louvre with her male friends in “Band of Outsiders,” and pondered the multitude of meanings implicit in a cup of coffee’s swirling surface in “Two or Three Things I Know About Her” (1967). They have swooned over the mad Technicolor collision of men and women, colors and styles in the magnificent “Pierrot le Fou” (1965) and the moody erotic languor of Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli in “Contempt” (1963), for many Godard’s supreme masterpiece and most emotional work, in which he grapples with the end of his marriage and also that of the Hollywood cinema he grew up loving.

The visual beauty of his work persisted and perhaps even deepened well after his storied ’60s period, those decades during which Godard transformed from a bespectacled, cigar-wielding New Wave icon into something altogether more challenging for many to embrace. For his most committed partisans, he discovered ever more freewheeling and exciting tributaries of cinematic meaning with movies like “First Name: Carmen” (1983), “Détective” (1985) and “Nouvelle Vague” (1990), along the way branching out into collaborative filmmaking projects and embracing the possibilities of digital video. For others, these decades were not a period of advancement but retreat, into ever more bewildering and even punishing realms of inscrutability.

I’d hardly be the first person to confess to finding my share of late-Godard movies perplexing, which is not to say I’ve given up on them, especially since I’ve also found my share of them deeply pleasurable, generous and sometimes gorgeous beyond words. One of his most rapturously received works of the last decade is “Goodbye to Language” (2014), a 69-minute astonishment of sight and sound that resembled some of his earlier work in its jagged allusions, its bursts of text and its beautiful women — but also, thanks to its dazzling experiments with 3-D, resembled nothing he’d ever made before.

“Godard forever,” an audience member yelled out as the lights dimmed on “Goodbye to Language’s” first screening in Cannes (some 46 years after the 1968 edition of the festival, which he and several other self-styled cine-revolutionaries brought to a screeching halt). Several months later, “Goodbye to Language” was named best picture of 2014 by the National Society of Film Critics — a decision that delighted various small pockets of the cinema-loving world and drew all-too-predictable accusations of pretension and elitism from some who’d barely heard of it, let alone seen it.

Heaven knows Godard didn’t make films to win prizes, let alone break box office records. But it was immensely satisfying to know that this unaccountably great and inventive artist, then 84 and in the twilight of a career that changed cinema and the world, was still capable of ticking off all the right people. Long may he continue. Godard forever.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.