Plaschke: Tommy Lasorda loved the Dodgers so much, he became the Dodgers

He was a giant with the eyes of a child, a fighter with the softest of hearts, a Hall of Fame manager who acted like a high school cheerleader, a stalking and howling and gesturing ball of contradictions who spent nearly seven decades following a single truth.

Tommy Lasorda loved the Dodgers. He loved them beyond all reason, at the highest of volumes, through every chapter of a 93-year-old life. He loved them as their struggling pitcher, as their fiery manager, as their headstrong executive, as their wisecracking ambassador. In the end, he loved them as a frail elderly gentlemen who watched his final games at Dodger Stadium in the owner’s box, huddled underneath his Dodger blue jacket, often alone, but always at home.

Tommy Lasorda was the first to bleed Dodger Blue and did so for nearly every bit of his time on Earth, spilling it across every corner of the world, until he died late Thursday night after suffering a heart attack.

It is fitting that the last game he attended in person was the Dodgers’ title-clinching victory over the Tampa Bay Rays on Oct. 27, 2020, in Arlington, Texas. He left the world as he created it, a blue heaven on earth.

I can hear him now, his gravelly voice thundering from somewhere above, his crooked finger jabbing down through the clouds.

“Lemme tell you something! There really is a Big Dodger In The Sky!"

Tommy Lasorda loved the Dodgers so much, he became the Dodgers, the interlocking “L” and “A” forming the beginning of his name, and his loss creates a gaping hole in their culture. There will never be another Tommy. The sports establishment has become too businesslike to create one and, if it did, sports fans would be too cynical to accept him.

Lasorda was more than the tough manager who won World Series titles in 1981 and 1988. He was also the guy who once seemingly coached an injured child out of a coma and eventually used him as a batboy.

Lasorda was more than the second-winningest manager in Dodgers history, with the second-most playoff wins. He was also a legendary eater who turned a weight-loss challenge from Orel Hershiser and Kirk Gibson into a campaign that built a new convent for the Sisters of Mercy in Nashville.

He was a poor kid who grew up the son of Italian immigrants, in a Norristown, Pa. tenement, and he spent his life as a reflection of those roots. He literally had to talk his way into Vero Beach’s Dodgertown when he arrived late for his first spring training in 1948, and spent the next six decades attacking life with both a chip on his shoulder and gratitude in his heart.

His impossibly large and eternally round presence owned every room into which he walked. I spent 32 years following him through those rooms, covering him as a beat reporter, chronicling him as a columnist, then spending a year with him writing a book about his life titled, “I Live For This!" In all that time, I’ve never been around a more magnetic personality. He sold the Dodgers. He sold life.

Up close, his powerful presence was cratered with incongruities. Sometimes I loved him for making people so happy. Other times I wanted to scream at him for delivering little slights to those who would challenge him.

He was always loud, always hungry, always scheming. But he was also always hugging, always giving, so much that his players’ children called him “Uncle Tommy."

One minute, he would be smiling and signing an hour’s worth of autographs for children. The next minute, he would scold one of the children for not being grateful.

He would remember nicknames and stories about every former player, and when those players returned after retirement, he would greet them like lost sons. But if he felt a former colleague had disrespected him, he would act as if they never existed.

He was a world-class curser, his profanity appearing in every possible sentence structure and conjugation. Here’s hoping the Big Dodger In The Sky doesn’t ask him his opinion of Kingman’s performance. But, in his unapologetic old-school fashion, he tried to never curse around women or children, and he once asked that all curse words be removed from our book.

He was an all-star eater, constantly surrounding himself with food, with pregame meals so big and messy that he would often have to change his uniform shirt before heading to the dugout. But he always insisted on sharing, his Dodger Stadium manager’s office serving as a free buffet open to all.

He made big money for motivational speeches, and would travel the country for the chance to make a buck. But he never charged schools, churches or the military.

He was, for a time, arguably the most famous baseball figure in the world. Yet he remained grounded in a modest neighborhood in Orange County. He was married to the same woman, saintly Jo, for 71 years. He lived in the same Fullerton home for 69 years. He remained the same old Tommy, for better and worse, forging ahead during even the deepest of personal tragedies.

In June of 1991, his son Tommy Jr. — known around the clubhouse as “Spunky," — died at age 33 from AIDS-related complications. Lasorda never publicly acknowledged that Spunky was gay, and consistently contested the cause of death. Yet by all accounts Lasorda was a loving and generous father, and was with his son in his final hours, telling him stories and bringing him soup. He also never stopped bragging about daughter Laura and granddaughter Emily.

I met Lasorda when I began covering the Dodgers full-time in the 1989 season. The first thing I learned was that, after fighting so long to be the center of attention, Lasorda hated to be alone.

If you hung out with him long enough, he would give you a scoop. If you were the last person sitting on his office couch before the game, he might even give you a headline. So instead of sitting in the dugout like other reporters, the Dodgers beat reporters would often plant themselves next to his desk for hours every afternoon, listening to his endless stories, helping him entertain his many guests, eventually hoping he would spill something about a roster move.

I always tried to be the last person Lasorda saw before the first pitch, because drama would often ensue.

One time he suddenly decided to take a shower, so I stood diligently outside the stall, steam soaking my notebook, as he gave me some roster insights.

Another time he found himself with extra pregame pizza, and begged me to eat with him just before the national anthem was played, but I had been eating his food all afternoon and couldn’t stomach another bite.

“Eat one more piece with me, and I’ll tell ya something," he suddenly shouted.

I ate. And just before Lasorda rushed out to stand for the flag, he gave me an injury report.

Lasorda loved an audience and, goodness, he could really work a crowd. I’ve seen him give speeches that ended with hundreds of salesman jumping to their feet and chest-bumping each other. I’ve heard him give talks that ended with a line of elderly women waiting to meet him while fighting back tears.

His best audience, of course, was his Dodger teams. His ability to make believers out of that 1988 championship squad was arguably the best motivational work in baseball history. They were heavy underdogs to the New York Mets and Oakland Athletics. They fielded what announcer Bob Costas called one of the worst lineups in World Series history. Yet with Gibson’s homer and Hershiser’s heroics, they found a way to win, and Lasorda was directly involved with the success of both men.

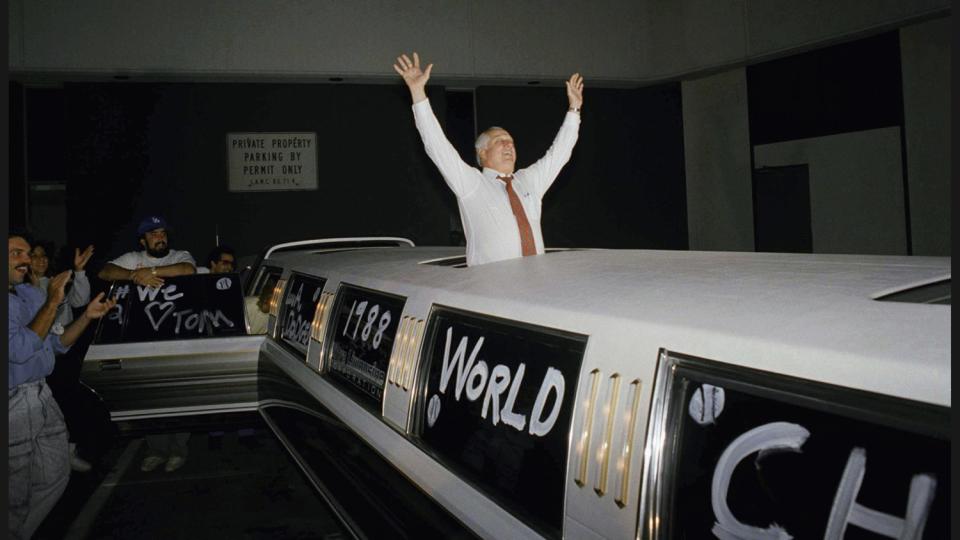

He gave Gibby room to run the clubhouse with a tight fist. He gave the bookish-looking Hershiser an unlikely nickname, “Bulldog," which helped turned the pitcher into exactly that. In the end, in the cramped Oakland clubhouse on that long-ago October night, he repeatedly jabbed his left hand into the air and gave a champagne-soaked victory speech that remains a thing of raw oratory beauty.

“Nobody thought we could win the division! Nobody thought we could beat the mighty Mets! Nobody thought we could beat the team that won 104 games! Nobody believed! Nobody!"

Another great motivational moment occurred during what Lasorda quietly considered his greatest achievement, forgotten by many because it occurred on the other side of the world. In the summer of 2000, at age 73, he led a group of minor leagues to a gold medal in the Summer Olympics in Sydney.

The Americans were huge underdogs to the vaunted Cubans. The Americans were so anonymous that Lasorda had trouble remembering their names. Yet he marched into Australia predicting victory and marched out after a championship game victory against, yes, Cuba.

It was clearly a highlight of a patriotic life, but even in this there was a bitter tinge. Awaiting the medal ceremony, Lasorda was standing gleefully by the podium at the Sydney stadium when he was given the bad news. Managers and coaches of Olympics teams do not receive medals. He would have to recede to the shadows.

He was crushed, but nonetheless sang the national anthem loud enough to be heard in the outback.

This passion worked both ways. If Lasorda felt someone wasn’t giving him his proper due, he would take that chip off his shoulder and throw it at them.

The most glaring example of these shuns could be found in Lasorda’s immediate managerial successor, Bill Russell. Lasorda never felt like Russell showed him enough respect. So for years after his firing, even though he still holds the record for most games played by a Los Angeles Dodger, Russell never found his way back to the organization.

Today that organization seems thinner, smaller, quieter. When Dodger Stadium is allowed to fill again, it will initially seem empty. Lasorda still has a museum-like office there. In perfect Tommy style, it contains a memento even for this moment.

On a shelf is his gravestone plaque.

“Dodger Stadium was his address, but every ballpark was his home," it reads.

The Dodgers were indeed his address, his heart, his life, and even the voicemail message on a cell phone whose number never changed.

“If you don’t cheer for the Dodgers, you might not get into heaven," Lasorda warned callers.

Today that heaven is a little louder, a little messier, and a lot more blue.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.