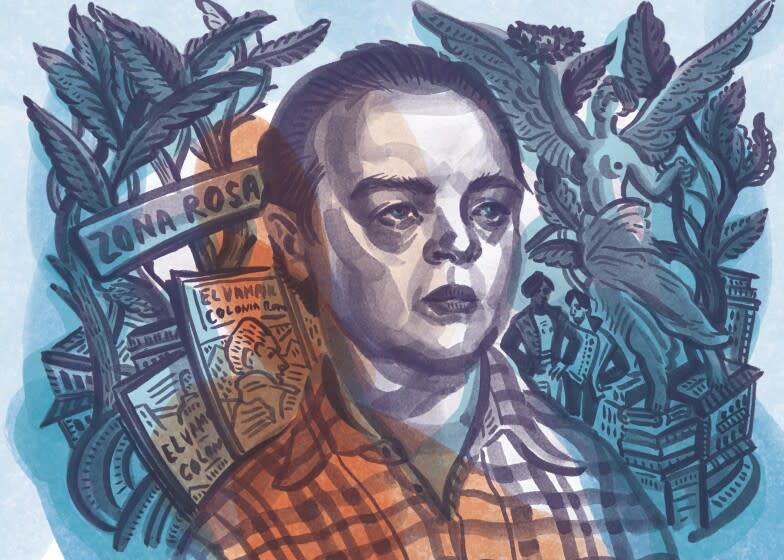

Appreciation: Why Luis Zapata's breakthrough gay Mexican novel demands a new translation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Here’s something the glossy guidebooks or cultural histories of Mexico City will not likely ever tell a doe-eyed visitor: The restrooms at the Sanborns chain cafe near the Angel of Independence monument were once the cruisiest place in town to find illicit sex.

For generations of men in the second half of the 20th century, long before cellphones and hookup apps, the “Sanborns del Ángel” was legendary. Gay and closeted men indulged in the thrill of quickies with strangers in the men’s room stalls, or picked one another up for later, to the eternal frustration of the staff.

Outside, at the tables, coffees lasted for hours. The Sanborns chain — owned today by the ultra-wealthy Carlos Slim — became a beacon for a burgeoning community, allowing gay people to gather at a time when the government was clamping down on social dissidents of every kind, including LGBTQ people.

This is the sort of illuminating cultural lore no one ever bothered to write down in Mexico — until the publication in 1979 of the novel “El vampiro de la colonia Roma,” or “The Vampire of Colonia Roma,” by Luis Zapata.

At the height of social control under the authoritarian rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, Zapata’s novel upended stereotypes of gay Mexican identity through the story of a lonely hustler named Adonis García. The narrator enthusiastically cruises for sex in the city, sometimes at the Sanborns near the Angel.

Though controversial when it was published, “El vampiro” quickly became a cult classic. To this day, it is beloved by gay and nongay readers alike.

On Nov. 4, Zapata, a native of Guerrero state, died at age 69 in the city of Cuernavaca. Although he was barely known beyond his country’s borders, even among Mexican Americans, the author played a singular role in shifting perceptions of LGBTQ people in Mexico’s consumable culture.

Mexico’s culture secretary, Alejandra Frausto, and the National Fine Arts and Literature Institute announced Zapata’s death in a statement and promised a public memorial after the COVID-19 pandemic. “With pain and affection we say farewell to Luis Zapata, pioneer of LGBT+ literature in Mexico,” Frausto said.

In a stream-of-consciousness style, radically lacking any punctuation and written in the bitterly accurate urban vernacular of the era, Adonis’ narration seemed to unmask an underground world. The novel arrived at the fringes of La Onda, a post-magical realist “wave” of countercultural urban art and expression. It displayed for the first time in modern Mexican literature a gay figure assuredly inhabiting their sexuality, a notion incompatible with Mexico’s perennially macho view of itself.

For “El vampiro’s” earliest readers, the audacious voice of the narrator was the book’s irresistible hook. Adonis describes trysts and affairs up and down Mexico’s caste-like class system, sometimes finding himself invited into the realms of upper-class society. These narrative hopscotches make “El vampiro” a paragon of the picaresque form.

“I don’t think anything important has ever really happened to me [...] like it does to a lot of people, where something happens that all of a sudden changes their lives,” Adonis says early in the novel, using long spaces to separate his thoughts. “I don’t think I got a destiny [...] or if I did, I must have lost it along the way.”

Gay writers of prominence had emerged from the fervor of the 1968 generation, led in large part by celebrated urbane essayist Carlos Monsiváis, or “Monsi,” as the writer was affectionately known. Monsiváis gained acceptance in the middle classes and on mainstream television by subtly distancing himself from the seedier aspects of gay life at the time.

Zapata, in contrast, embraced it. “He created an unforgettable protagonist, an archetype of gay literature,” said Juan Carlos Bautista, a poet and friend who published alongside Zapata with the small queer press Quimera. Bautista remembers first reading the book furtively as a 17-year-old, when he was emerging into his own gay identity.

“Luis totally flipped the definition that popular culture had about homosexuals, which was as depraved figures, submerged in desperation and tragedy,” said Bautista, reached by phone in Xalapa, Veracruz. “Adonis presents himself as proud of his sexuality, and he does not apologize for existing.”

Though Zapata is mostly unknown north of the border, there is an English translation: In 1981, the old-school San Francisco publisher Gay Sunshine Press produced “Adonis Garcia: A Picaresque Novel,” with the late Canadian translator Edward A. Lacey. Three copies are currently available in the Los Angeles Public Library collection, but a curious reader should be wary. Lacey gives Adonis a kind of late ’70s New York wise-guy voice, which simply doesn’t work.

“I really appreciate the effort that [Lacey] gave it, under very difficult circumstances," said Clary Loisel, translator of the only other title by Zapata available in English. “But there’s so much slang and so many Mexicanisms, so many references to specific areas in Mexico City and the Colonia Roma, you have to have a real cultural insight to even place the language. You have to be almost bicultural to get it.”

A professor of Spanish at the University of Montana at Missoula, Loisel translated Zapata’s “The Strongest Passion,” a less daunting feat than “El vampiro,” as the book is a narrative dialogue. Loisel interviewed Zapata and once took Spanish students to Mexico to meet him.

He has also taught the novel as a visiting professor in Guanajuato, in conservative central Mexico, and found that most of his students had already read it. “I’m not sure anybody was gay in that class,” Loisel recalled. “It’s sort of an underground canonical work.”

The emerging gay metropolis

Back when “El vampiro” first appeared, it was a weird time to be gay in Mexico.

The ruling party had massacred protesting students at Tlatelolco just before the 1968 Olympic Games, and the economic and cultural liberalizations of the 1980s were years away. The authorities, with the support of Mexico’s conservative and often reactionary middle classes, conducted stings aimed at suppressing overtly gay behavior in major cities. The slurs of “puto” and “maricón” were common put-downs.

And yet, since the early 1970s, Juan Gabriel, the pop vocal powerhouse and femme icon from Ciudad Juarez, had released a steady string of hit records to adoring audiences on national television.

In truth, Mexico City in the 1970s was already an exuberantly gay metropolis. The cultural engine of the television and movie studios, plus the vibrant theater scene and a complex network of universities and arts institutions, helped the queer ecosystem thrive. The neighborhood of Zona Rosa, where the Sanborns in question still stands today, was a glittery gay hot spot teeming with clubs, galleries and cafes.

Drag shows and “Miss Mexico” contests were common, according to Guillermo Osorno, author of a nonfiction book on the city’s gay underground, “Tengo que morir todas las noches” (I Must Die Every Night).

“It was a sort of parallel to what you see in ‘Paris Is Burning,’ transplanted here to Mexico City,” Osorno said, while “the PRI was at the pinnacle of its power.”

In 1978, Mexico had its first ever public demonstration of gay people: a small group within a march commemorating the Cuban Revolution. The first full gay pride march took place a year later, just as “El vampiro de la colonia Roma” hit bookstores. (A “colonia” is a neighborhood, and Roma is the Beaux Arts colonia in Mexico City, considered artsy and cool today).

“The first gay and lesbian organizations emerged in those days, so it was a moment of great integration into what we now know of as our community,” said Odette Alonso, a writer and longtime friend of Zapata’s in Mexico City. Of the book, she added: “More than anything, I will never forget the thing about the restrooms at Sanborns. It’s just remarkable, in his detail.”

(Alonso noted that the first openly lesbian novel in Mexico, “Amora” by Rosamaría Roffiel, did not arrive until 10 years later.)

The most telling scenes in “El vampiro” capture juxtapositions — romps in the stalls of a cafe chain with a mannered “Mexicanist” ambience — that reflect the core tension of gay Mexican life in the period between the tumult of the 1960s and the advent of cellphones. It was somewhere between outside and in, encompassing all the gray areas in between.

Zapata’s revolutionary novel portrays a culture that was always “finding ways to inject itself into the incisions between the public and private,” Osorno said, which is what makes it, ultimately, forward-looking and hopeful.

“He broke that silence,” said Bautista. And now, so many decades later, even as the internet has helped facilitate gay socialization and connectivity beyond the borders and boundaries of the 1970s, his work remains a road map for living without fear or shame. “Despite all of his ambivalences," Bautista said, “‘El vampiro’ remains a model of liberation.”

The only barrier left for “El vampiro” is language. All it would take is one brave soul to shoulder the task of re-translating the voice of Adonis García in a way that matches (or challenges) the sensibilities of contemporary American English. In today’s literary climate, the translator would also have to settle on a single form of American slang to sustain the character.

Anyone? ¿Alguien?

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.