Will Arab Americans finally be counted on the US census?

Community leader Rania Mustafa wants better political representation for Palestinian Americans but can’t find a reliable count of how many people of Palestinian ancestry live in New Jersey.

Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh faces calls to diversify police, but the 25-plus Arab Americans on the police force are counted in official reports as white.

Khalid Bader does not know whether medicines he dispenses at a pharmacy in Paterson will affect people from the Middle East and North Africa differently, because he doesn’t have that kind of data.

The Arab American experience in this North Jersey enclave reflects a larger problem, advocates say. Legally counted as white since 1944, Arab Americans have been overlooked on the U.S. census, an omission that has obscured their needs in areas like health, employment, education and housing.

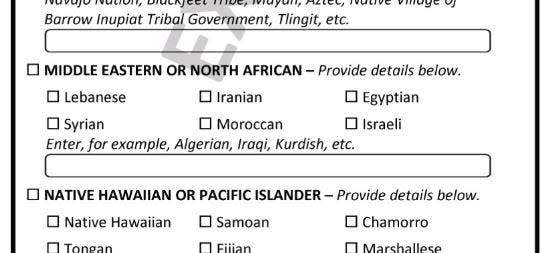

But that could finally change under a proposal to add a Middle East and North Africa, or MENA, category to the U.S. census. Under the revised format, people could indicate if they are of MENA background and identify their country of origin, including 22 Arab-majority nations as well as Iran, Turkey and Israel.

The fight to recognize MENA on the census stretches back two decades and through several presidential administrations, said Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab American Institute, an advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. The organization has led campaigns for census changes, arguing that the data it yields plays a crucial role in determining access to resources from education to roads and health care.

“Literally everything is impacted by census data, and data sets policy,” Berry said. “If you’re rendered invisible in the data, your representation and services the community might need are harmed by that.”

A box that fits

Early Arab immigrants, who were mostly from modern-day Lebanon and Syria, fought to be counted as white at a time when the U.S. Naturalization Act — a 1790 law that was in place until 1952 — restricted naturalized citizenship to whites. Newer immigrant waves have been more diverse and felt a greater affinity with minority groups.

Over time, and as the law changed, community leaders said the categorization hurt them and cost them dollars, services and recognition. Census data can affect funding for education, health care, social programs and voter outreach. It can affect inclusion in research on topics like housing and health and in opportunities for scholarships and business loans. And as an uncounted community, its leaders felt they had less political leverage.

For Noran Elzarka, an Egyptian American woman from Harrison, checking the "white" box on the census never felt quite right. As she was growing up after 9/11, her community was surveilled and informants were placed in mosques, she said.

“I’ve never been treated as white,” Elzarka said. “I wear a hijab. I am Arab. I appear Muslim.”

Elzarka welcomed news of a possible change to the census. “It allows people from the region to feel included and to feel like their identity and where they come from matters,” she said.

Still, Elzarka said she wanted assurances that information will be used only for demographic purposes, and not something “shady.” It’s a common concern among Arab Americans, who fear that information will be used for police surveillance or immigration enforcement. Bader, the Paterson pharmacist, said that if changes are adopted, agencies need to be proactive and explain why they are asking more detailed questions.

“With misinformation and conspiracy theories, people are reluctant to give their information,” said Bader, past president of the National Arab American Medical Association’s state chapter. “They’ll wonder ‘Why do you need to my ethnicity to get my vaccine?’ They need to be straightforward about why we are doing this.”

How many Arab Americans?

Currently, the Census Bureau conducts sample surveys about ancestry in the U.S., but advocates say they undercount minority groups like Arab Americans. The bureau estimates there are 2.1 million, but the Arab American Institute gives what it describes as a conservative estimate of 3.7 million.

Without accurate data, the institute does not have a complete picture of how many Arab Americans live in the U.S. or where they are concentrated, even as it advocates for them in politics, voting and civil rights.

“Our voter engagement project is about political empowerment of our community,” Berry said. “I wish I could run our Yalla Vote campaign based on where we are concentrated and our largest numbers. Without census data, it makes our job very difficult.” (Yalla Vote is a voter mobilization campaign; yalla means "let's go" in Arabic.)

In Paterson, these concerns are shared by the city’s mayor. Sayegh would like to tally police officers of MENA ancestry, which would show that the force is more diverse than reflected in reports. At least two dozen people in the Police Department have Middle Eastern or North African roots, Sayegh said. He gave the example of Officer Serein Tamimi, a Palestinian American, hijab-wearing police officer who began in 2019.

“She shouldn’t be counted as white,” he said.

Rania Mustafa, executive director of the Palestinian American Community Center in Clifton, believes numbers of people from MENA countries are much higher than census estimates. She hopes that with an accurate count, marginalized communities will gain a greater voice and political power.

But the proposed line of questions also sparked complaints. The sample survey lists only six examples of ethnicities and asks people to write in if they are of another ethnicity, so some groups still feel excluded. Mustafa also worried that inclusion of Israelis, one of the six examples, would distort or undercut the purpose of a MENA category.

“It very much highlights a category of people that has a different experience than others in MENA,” she said, adding that the push for MENA is about "moving away from white."

The addition of a MENA category on the census is one of a number of proposed changes to race and ethnicity questions. An advisory panel is taking public comments about revisions until April 12 and expects to submit final recommendations by the summer of 2024. Comments can be submitted to the federal Office of Management and Budget online. Any changes that are adopted would apply to the 2030 census.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: US census ethnicity categories: NJ Arab Americans want inclusion