From the archive: The agonizing death of Detroit’s old city hall

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Free Press Flashback revisits the beginning of the end of Detroit’s ornate seat of government. The beloved building was inaugurated in 1871, but became expendable, in the eyes of city officials, after what is now called the Coleman A. Young Municipal Center opened in 1955. Preservationists waged a long campaign to save it. This story ran on page 1 on Aug. 15, 1961. After the article is a host of facts about Old City Hall, featured on historicdetroit.org.Old City Hall began to die Monday night.

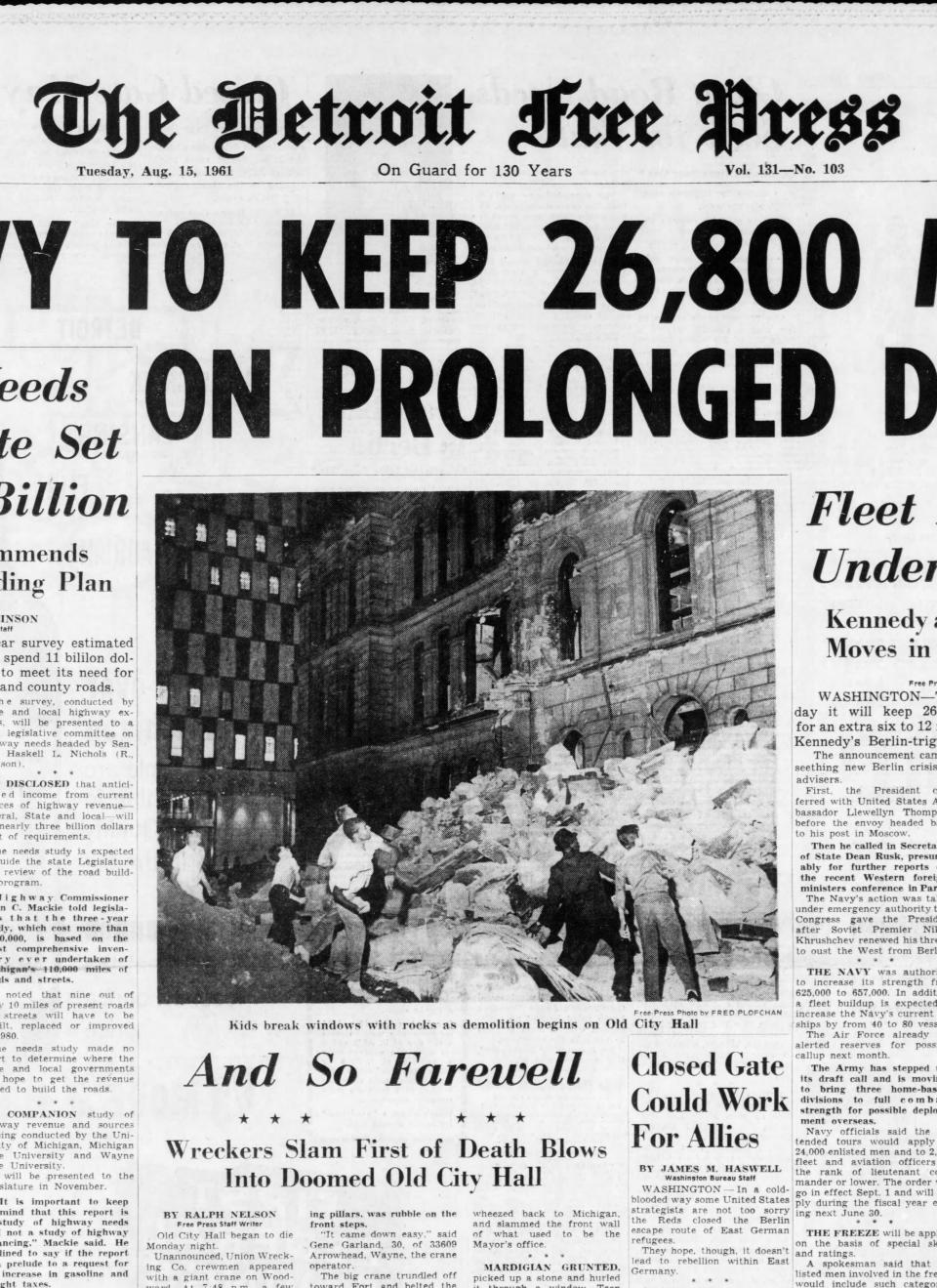

Unannounced, Union Wrecking Co. crewmen appeared with a giant crane at Woodward and Michigan at 7:48 p.m.. A few minutes later, a 4,800-pound wrecking ball slammed into the historic building.

The ball hit the upper left corner of the porch roof section and a huge piece of Amherst stone fell in a cloud of dust.

“The old building has reached the point of no return,” said Henry Mardigian, Union president. “This is the day our contract starts and we're here to do the job."

In 25 minutes, the porch roof section, with its supporting pillars, was rubble on the front steps.

“It came down easy," said Gene Garland, 30, of 33609 Arrowhead, Wayne, the crane operator.

The big crane trundled off toward Fort Street and belted the front of the building. Then it wheezed back to Michigan and slammed the front wall of what used to be the mayor's office.

Mardigan grunted, picked up a stone and hurled it through a window. Teenagers in the crowd grabbed stones and joined him. Old City Hall stood quietly, accepting the indignity.

Reporters scanned the watchers. Not a city official could they see; no one had come to watch the death of the structure that for 92 years had been the hub of Detroit.

The building dodged death for decades

Mardigan said the “token” attack on the building Monday would be the last outside work his company would do for about two weeks. Twenty five stones are going to be pried out of the building to be used for bases for historical markers. The tower clock will also be saved.

In two weeks, “a bigger crane, with an 8,000-pound ball, will really work the building over," he said.

There have been many campaigns to get rid of the building.

One in 1926 was intense. Ditto 1935. Many Detroiters however, loved the ponderous stone structure.

“Never while I am alive,” said the late John C. Lodge, onetime mayor and Common Council president.

Lodge led a group of politically and financially powerful men who angrily resisted destruction proposals. But they have long since passed. Preservationists waged a ferocious legal and public relations battle in recent years to save the building, but time ran out.

Recalling the mayors, good and bad

Old City Hall has been stripped for doom for weeks. Statues and cannon are gone. The life-size portraits of almost 100 years of mayors that once lined the lofty first floor corridor are gone.

Mostly, the mayors who occupied the city hall were honorable men, like Hazen Pingree and Edward J. Jeffries and Al Cobo. Some were lesser men. Some fathered scandals.

Charles Bowles was recalled during Prohibition. Richard Reading was jailed for taking graft in the mid 1940s. But the honorable men were numerous enough to keep Detroit moving ahead decade after decade.

The councilmen, too, in vast majority, were dedicated people who loved the town. There were Lodge and James Garlick and John Kronk and a legion of others.

But some of these, too, were lesser men.

Memories now ...

Friends who fought to save the building in this final campaign were finally squelched Monday in Federal Court when Judge Theodore Levin ruled he had no jurisdiction over a final petition to restrain the wreckers.

So, hours after Levin ruled, the wreckers arrived.

The site of Old City Hall became Kennedy Square, a lively gathering space on a landscape of cold concrete. It was replaced by the One Kennedy Square building in 2005.

(Editor's note: The reporter’s 1961 characterization of Mayor Cobo as an “honorable” man has been reassessed in recent years in light of Cobo’s racist actions while running Detroit in the 1950s. Officials removed his name from Detroit’s convention facility in 2018.)

Old City Hall Facts

Source: historicdetroit.org

Dedicated: July 4, 1871Builder: N. Osborn & Co. of Rochester, N.Y.

Cost: $379,578, about $8.24 million today

Style: Italian Renaissance and French Second Empire

Description: The building stood three stories high, made of cream-colored Amherst sandstone quarried from near Cleveland.

The clock: In the middle was a clock tower, which loomed 180 feet above the street. The building predated the city’s first skyscraper by nearly two decades, so it literally towered over the city for years.

One of the nation's top clockmakers, W.A. Hendrie of Chicago, created the giant timepiece especially for Detroit and regarded it as his masterpiece.

Its four dials ― each 8 feet, 3 inches in diameter and made in Glasgow, Scotland ― were illuminated at night so citizens across downtown could see the time.

When its 125-pound pendulum first swung into action at the building’s formal dedication on July 4, 1871, it was the largest clock in the United States.

Cute tradition: No one knows when or how the custom started, but the magic of its booming bell on New Year’s Eve summoned hundreds of couples to City Hall, where they would kiss at the stroke of midnight.

Interior: Outfitted with black walnut and oak furnishings relieved by woods of lighter color. The courtrooms and offices were filled with natural light pouring in through 15 large windows on each floor.

“There is not a single room or hall that needs to be artificially lighted from sunrise to sunset,” Harper’s Weekly noted in an 1871 article.

The building was said to be fireproof, with beams made of iron and the black and white marble floors laid upon brick arches. Its grand staircase was cast of iron. Two iron fountains stood out front, as did cannons captured in the War of 1812 by Cmdr. Oliver Hazard Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie on Sept. 10, 1813 ― a battle that sealed American victory.

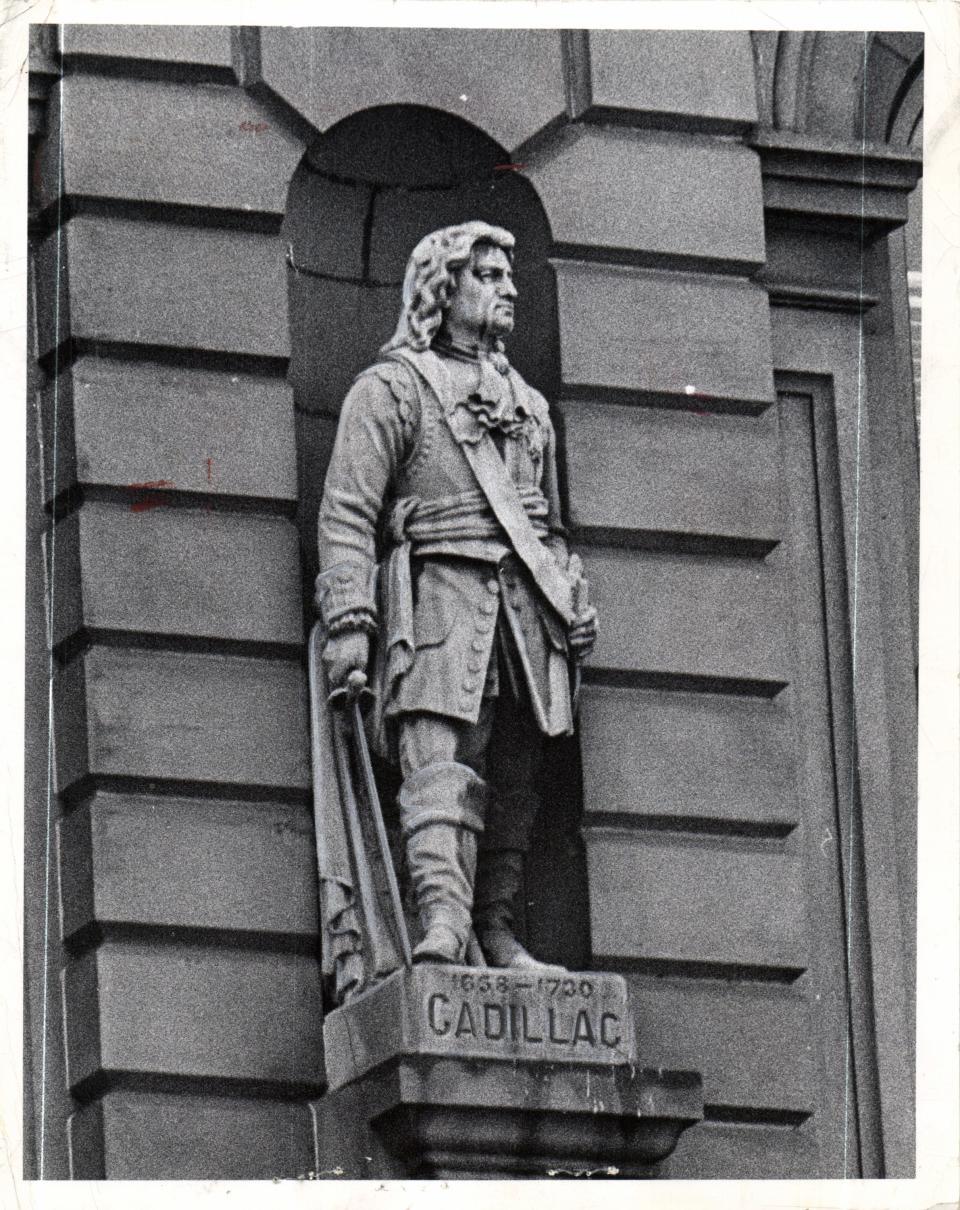

Exterior statues: In niches on the building’s corners were four statues recalling the city’s French heritage: city founder Antoine Laumet de la Mothe Cadillac, Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette, explorer Robert Cavalier Sieur de LaSalle, and Father Gabriel Richard, co-founder of the University of Michigan. They stand today at Wayne State University.

The fight to save the building: After years of debate and study, in January 1961, the Common Council voted, 5-4, to demolish the building. Mayor Louis Miriani was strongly in favor of tearing it down.

Groups fighting the demolition immediately vowed to seek injunctions. A move to circulate a petition in an attempt to get the issue on the ballot also was announced, but were ruled to have been submitted too late.

Lawsuits bought more time but could not spare the building. Crews of the Union Wrecking Co. had started tearing out interior partitions and fixtures on May 23, 1961, but court battles kept the wrecker’s ball at bay.

In July 1961, the U.S. District Court of Appeals ruled against Council President Mary Beck, saying that federal courts had no jurisdiction in the matter. The final straw came Friday, Aug. 11, 1961, when both the Federal Court in Detroit and the state Supreme Court rejected petitions for injunctions to stop demolition. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to take up the case.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: From the archive: The agonizing death of Detroit’s old city hall