From the archives | Arsons symbolic of racial divide: Fires fuel concerns that history is repeating itself

This story originally published July 2, 1996. It is being republished as part of the commemoration of USA TODAY's 40th anniversary on Sept. 15, 2022.

The first reported Black church arson occurred in 1822 when the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., was torched when whites learned slaves were meeting to plan an insurrection.

Eight generations later, the fiery destruction of Black churches remains a potent symbol of the struggle for racial equality that has long divided the United States.

To many African-Americans, burning a Black church is more than an attack on a house of worship; it is an assault on the culture itself.

"It is an attempt to show absolute contempt for whatever is of greatest value or whatever has greatest meaning for Black people,'' says C. Eric Lincoln, professor emeritus of religion at Duke University.

Today, the image of a Black church in flames appears against a backdrop of events that have torn at the country's racial fabric, from the Rodney King beating to affirmative action.

"We are dealing with a pattern that grows out of racial hostility in this country,'' says Deval Patrick, assistant attorney general in charge of civil rights enforcement at the Justice Department.

Which is one reason it's almost instinctive to assume a racial motive lies behind every Black church fire.

The reality is that both Black and white churches are torched by the hundreds each year for a long list of reasons, and there's been criticism of the tendency to point at race as the central problem.

Bruce Fein, a conservative constitutional law expert, says people are behaving like "the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland: Sentence first and reach a verdict afterwards.''

But to civil rights leaders and many Blacks, the sight of a burning church is an image that resonates with a moral and historical significance that ties the nation to its past of slavery and segregation.

From the poetry of Alice Walker to films such as Mississippi Burning, artists have used the image of a burning church or cross as a symbol of racial hatred.

While white churches fall victim to arson, few are burned for racial reasons.

The Black church has "been the heart of Black advocacy in America,'' says Joseph Lowery, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. "They are attacking the soul of the black community.''

The central role of churches in Black life goes back three centuries. Slave owners hoped the promise of glory in the afterlife would dull the hardships slaves suffered. But the church quickly became the one place where slaves could bow their heads voluntarily, in supplication to God, rather than to whites as an enforced custom.

Black ministers were among the most prominent leaders of the abolition movement. Churches were the foundation for the Underground Railroad. Slaves were secretly taught to read and write in churches.

After the Charleston church fire 174 years ago, many Southern states outlawed Black churches. In the states that allowed them, restrictions were put in place to keep Black churches under control.

A North Carolina law mandated that "five good, white men must be at any religious meeting that Blacks could attend. And in South Carolina, there was a law that no meeting of black people under the cover of religion could be held after the sun went down and before sunrise.''

An early wave of church burnings occurred in the 1890s, at the same time that many post-Civil War laws aimed at aiding former slaves were being overturned.

The modern civil rights movement also made Black churches targets.

In 1955, Holt Street Baptist Church was one of the headquarters of the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott. Martin Luther King Jr., then 26, was thrust to the front of the civil rights movement.

In 1964, freedom riders slept, ate and held voter registration drives in churches, usually Black churches. During the historic five-day march from Selma, Ala., to Montgomery in 1965, churches were the havens.

"Churches were the only place that Black folks could meet,'' Lincoln says. "And because everyone knew the churches were the center of the movement, they bore the brunt of hatred and were burned.''

The civil rights era saw another wave of attacks on Black churches. In Mississippi, 34 Black churches burned in three months during the summer of 1964.

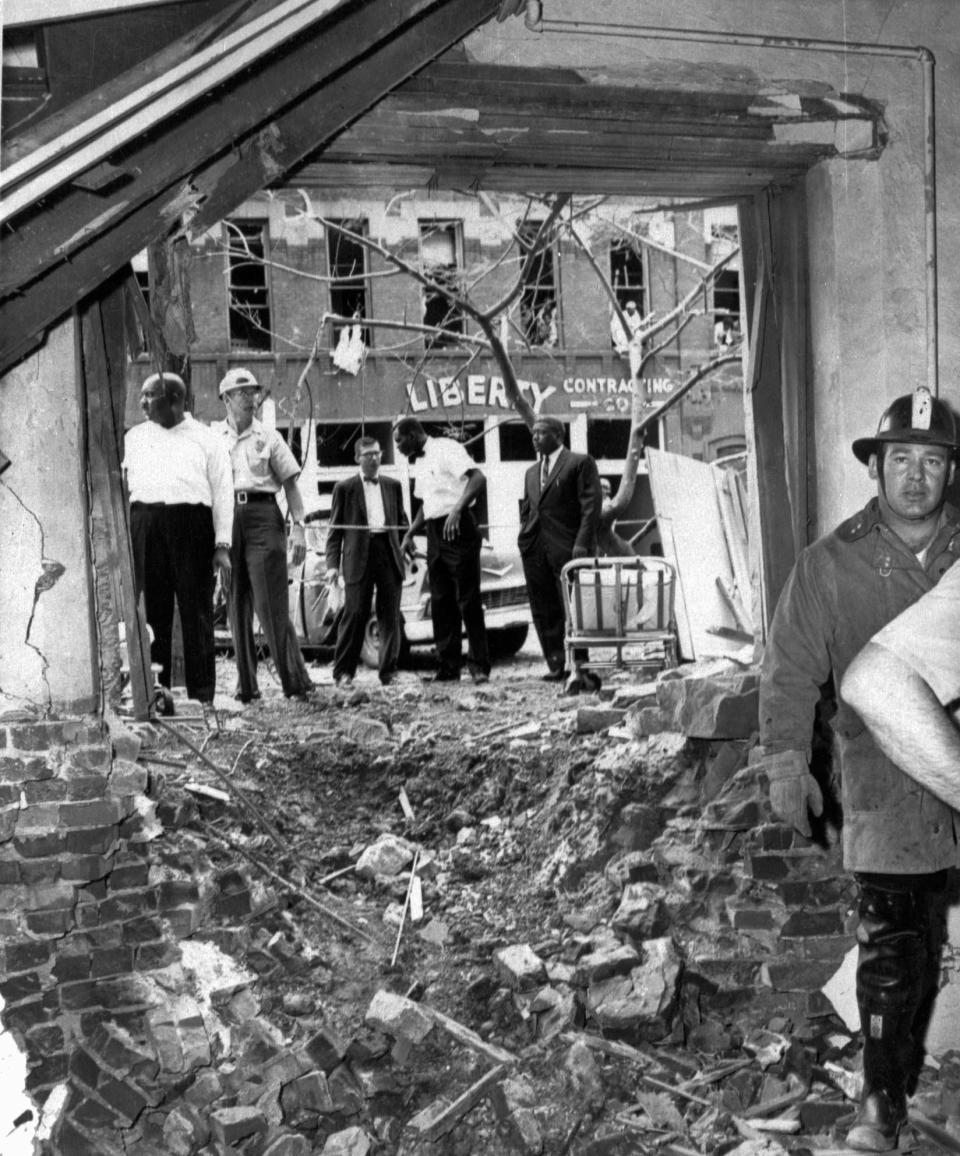

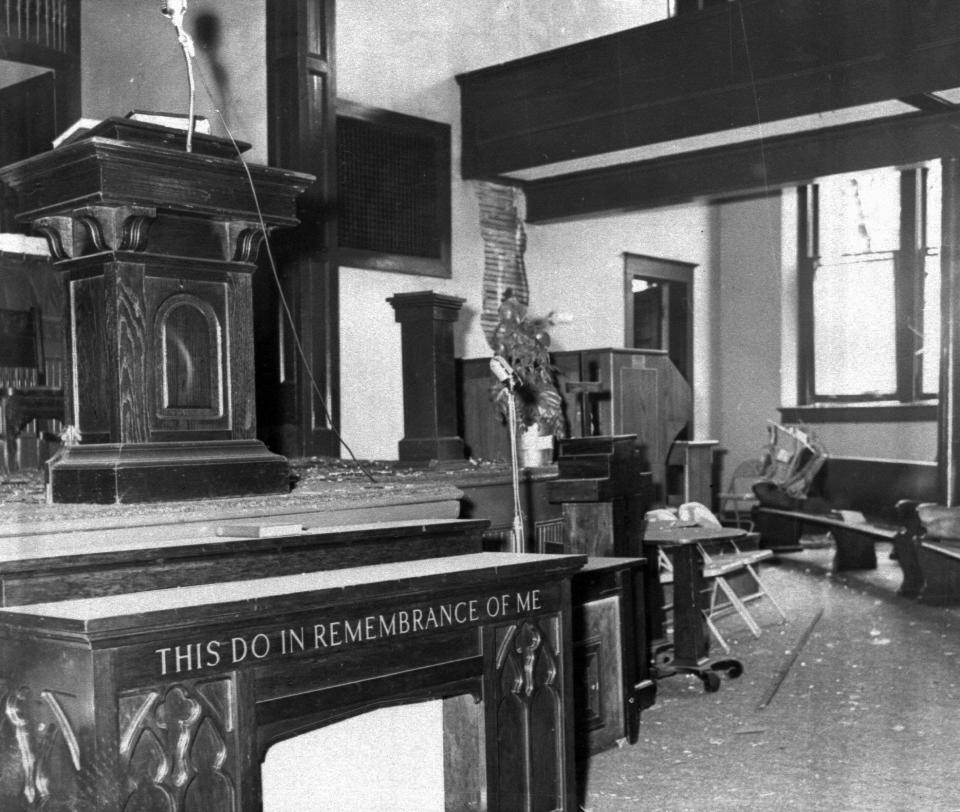

But the attack that most shook the nation was the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala. Left dead were Denise McNair, 11, and three 14-year-olds: Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Addie Mae Collins.

That most of the 66 Black churches burned since Jan. 1, 1995, were founded by slaves or freed slaves adds to concerns that history may be repeating itself.

The Black church fires in the 1990s also come amid a series of highly publicized incidents that have strained race relations.

The Rodney King beating in 1990 was followed by the acquittal of the white police officers who clubbed him. That prompted the Los Angeles riots in 1992 that included the videotaped attack on white trucker Reginald Denny, who was pulled out of his truck and pummeled with bricks by a Black man.

In the Susan Smith and Charles Stuart cases in North Carolina and Boston, respectively, whites played on the image of the Black criminal to create fictional perpetrators to cover up crimes.

On Dec. 7, a Black couple in Fayetteville, N.C., were shot on a city street. Police say they were killed by three racist skinheads who were soldiers from Fort Bragg.

Polls last year showed white America and Black America sharply divided over the O.J. Simpson verdict -- and whether the justice system is fair.

"We would all like to believe that we live in a color-blind society . . . where race doesn't matter,'' says Sen. Joseph Biden of Delaware. "But we don't.''

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the FBI have more than 200 agents investigating every Black church arson, no matter how little the damage. Federal authorities hope the fire investigation can help restore the faith of the Black community in law enforcement.

Pastors at burned churches have preached against jumping to conclusions.

In describing the fire at Salem Baptist Church in Fruitland, Tenn., the Rev. Daniel Donaldson concedes, "My heart says it's race, but reality says, 'Dan, what is that conclusion based on?' It might be race, but let's make sure it is.''

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Arson on Black churches symbolic of racial hostility in US