From the archives | The hidden power behind the Supreme Court: Justices give pivotal role to novice lawyers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story originally published on March 13, 1998. It is being republished as part of the commemoration of USA TODAY's 40th anniversary on Sept. 15, 2022.

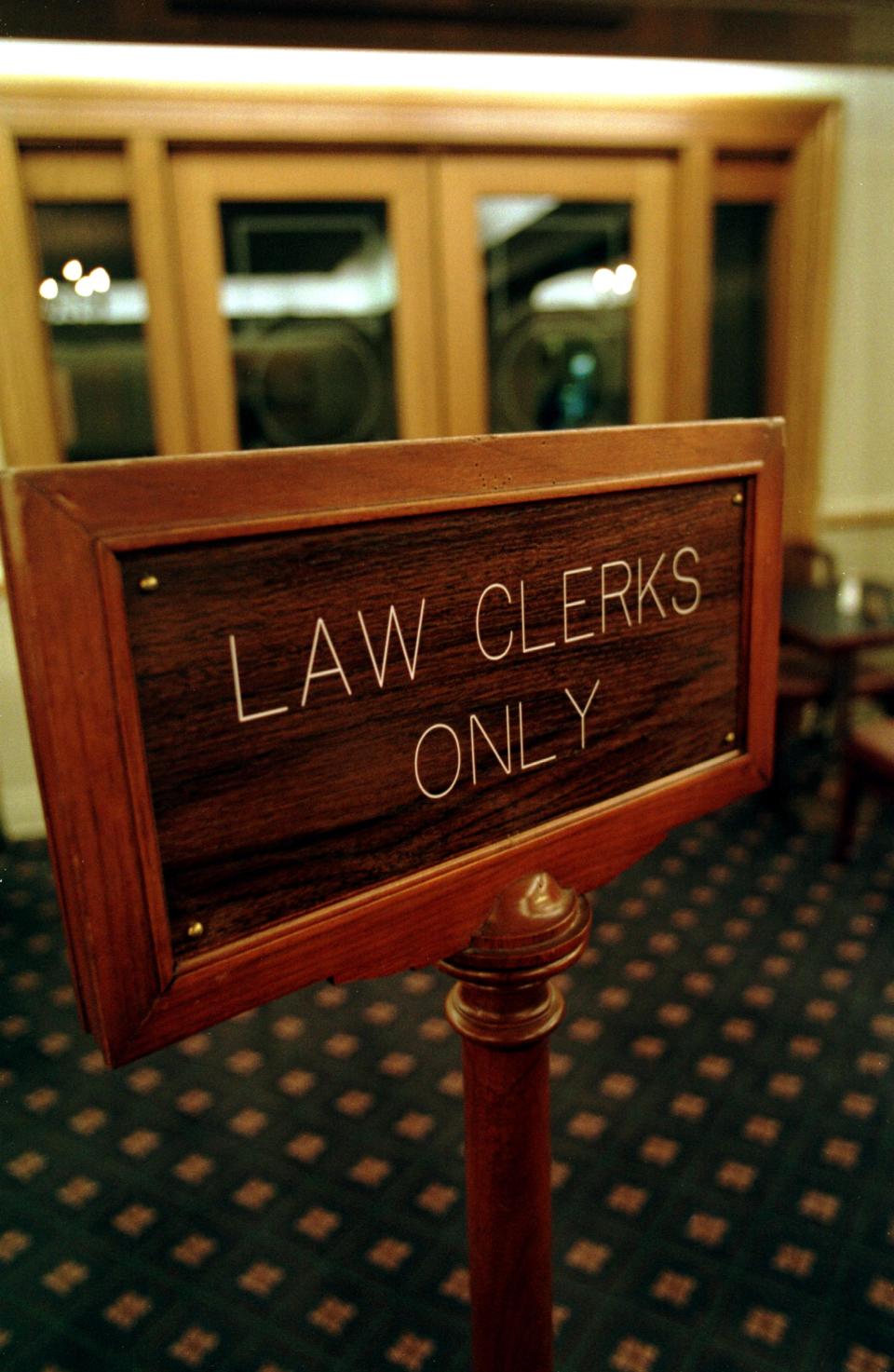

WASHINGTON -- They are the most powerful, least known young lawyers in America. They are the law clerks of the Supreme Court.

For an intoxicating year, 36 young men and women quietly screen most of the cases that come to the nation's highest court and write most of the words that come out.

When citizens or companies take a case "all the way to the Supreme Court," their petitions almost always are looked at first by the law clerks and disposed of without any justice actually reading the briefs. A single law clerk, typically 25 years old, white, male and a year out of Harvard, can guide the fate of a multibillion-dollar commercial dispute or make the difference between life and death for a condemned prisoner.

And when the court hands down a ruling that changes the course of society -- whether on race, the right to die or school prayer -- law clerks write the first drafts that have enormous influence in shaping the final opinions.

USA TODAY spent five months studying the effect and growing influence of law clerks. Current clerks are barred from talking to the media, so the newspaper interviewed more than two dozen former law clerks. Many others declined to talk publicly and sought to downplay their roles as indispensable but supporting positions in processing the roughly 7,600 petitions placed before the court each year.

But a growing number of legal scholars, as well as some justices themselves, are expressing concern that the clerks have become too powerful, usurping some of the key roles the justices used to play in the work of the court. A soon-to-be-published tell-all book by former clerk Edward Lazarus adds fuel to the debate by telling stories, some of which already are being disputed, of conservative clerks manipulating moderate justices during a politically divisive period 10 years ago.

"Justices yield great and excessive power to immature, ideologically driven clerks, who in turn use that power to manipulate their bosses and the institution," Lazarus writes in his book, Closed Chambers.

In its independent investigation, USA TODAY found few signs of ideological manipulation by today's clerks. But the newspaper did identify several effects of the clerks' largely unseen and unaccountable power over the screening and drafting of cases:

Delegating the court's work. Eight of the nine justices now routinely allow their clerks to write the crucial first drafts of the opinions they write. And eight of the nine, through a pooling arrangment, also give the clerks the key job of making the initial review of incoming cases, a task that helps determine just which cases the nation's highest court will consider.

Even the ninth justice, John Paul Stevens, does not always review incoming cases or write all of his opinions. USA TODAY has learned that key parts of his landmark ruling last year that struck down the law barring indecency on the Internet were written by Stevens' clerks. Stevens declined to comment.

Last term, with the court's docket filled with major cases -- doctor-assisted suicide, religious freedom, as well as Internet indecency -- clerks played an even bigger role than usual, court sources say. Clerks, as well as justices, pulled all-nighters to finish the court's work last June.

Shrinking the court's docket. For reasons that have mystified court-watchers, the court has been deciding just over half the number of cases per term than it did a decade ago. A key reason, Stevens told USA TODAY, is that clerks, who tend to be cautious about recommending cases for the court to take, have far greater power over the screening of new cases than before. Some critics also say the clerks pass up important but seemingly less interesting business cases.

Complicating its doctrine. Every word of Supreme Court rulings is dissected and interpreted by lawyers and lower court judges for years after they are issued. With more of the writing in the hands of clerks who lack self-assurance and experience, scholars say the court's rulings now are more often written in hairsplitting, tentative prose that leaves key issues unresolved. The clerks also write more than the justices might have. The court is putting out twice as many separate writings -- opinions, concurrences, dissents -- per case than it did 50 years ago.

These are, in the words of Yale Law School Dean Anthony Kronman, "strategies of insecurity."

As the clerks' power grows, who they are and how they are picked become questions of growing public importance.

A first-ever tally of the 394 clerks hired by the nine current justices during their tenures, conducted by USA TODAY, finds they are overwhelmingly white and male: fewer than 2% are African-Americans, just one in four is female. (See story, 12A.)

Four of the nine justices -- Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia and David Souter -- never have hired a black clerk. This year's clerks include no African-Americans.

In fact, the court itself, with two women and one black man, is more diverse than this year's law clerks.

Concern about the clerks' growing power is heard from many quarters.

Influential Chicago U.S. Appeals Judge Richard Posner likens the justices' growing use of the clerks to "brain surgeons delegating the entire performance of delicate operations to nurses, orderlies and first-year medical students."

Emory University professor David Garrow, author of several books on the court, says, "Inside the fraternity, inside the court's family, everyone knows that the clerks have significant influence. But it's a family secret that's not supposed to be discussed outside."

And William Domnarski, author of a book on the court's opinion-writing, says, "I don't think for a moment that the clerks decide the cases, but they put in all the reasoning, and that is a mind-boggling responsibility for people just out of law school. It's a fraud."

Publicly, both clerks and justices insist that the justices are firmly in control.

"The justices work very hard," says Stevens, the only member of the court who would discuss the clerks. "The idea that the clerks do all the work is nutty," he said in an interview late last year.

Yale law professor Harold Koh, a former clerk for retired Justice Harry Blackmum, also thinks it is a mistake to view clerks as powerful independent of their justices. "They are like the students of Michelangelo," says Koh. "They may put the ink on paper, but it is according to the justices' design."

Still, Stevens acknowledges that the role of the clerks is growing more important.

When he clerked for Justice Wiley Rutledge 50 years ago, Stevens says, "I had a lot less responsibility than some of the clerks now. They are much more involved in the entire process now."

Deciding life or death

That process begins with the screening of new cases, or petitions, that come to the court. The Supreme Court, unlike almost every other court, has near-total control over which cases it will hear.

Whether they involve the life and death of someone about to be executed or a major constitutional or commercial dispute, the petitions can be accepted for review or rejected out of hand.

Now much of that discretion is controlled by the law clerks.

"When I tell clients who have cases with hundreds of millions of dollars on the line that a bunch of 25-year-olds is going to decide their fate, it drives them crazy," says Carter Phillips, a former law clerk for late Chief Justice Warren Burger whose powerful Washington, D.C., law firm often argues before the court.

For most of its history, Supreme Court justices themselves read all the petitions, even though each has had at least one law clerk since 1882. Justice Louis Brandeis, who served from 1916 to 1939, boasted that the Supreme Court was respected because "the justices are almost the only people in Washington who do their own work."

But in 1972, faced with a growing caseload, the court started a "pool" arrangement. Under it, a single law clerk reviews and summarizes an incoming petition for all the justices in the pool and recommends whether the case should be reviewed by the court. The justices then vote whether to take up the case based on the time-saving memorandum.

Early concerns that the summarizing clerks could improperly sway the court were alleviated by the fact that at least four justices stayed out of the pool, serving as something of a check on the accuracy of the pool memo. The late Justice William Brennan Jr., the last justice to read every petition that came in the door, said he used to find three or four important cases a year that the pool clerks had missed or downplayed.

But Brennan left the court in 1990, and, over time, all the newer justices have joined the pool. Now only Stevens is out of the pool and not relying on the pool memorandums.

But even Stevens rarely reads petitions himself. He said his clerks dispose of about three-fourth of the cases without sending him any memorandum at all. For the rest, Stevens says, his clerks produce memos for him more useful than the pool memos. "When a clerk writes for an individual justice, he or she can be more candid," he says.

At the end of the screening process, the court agrees to consider fewer than 100 cases a year: just over 1% of the cases put before the court. The rest are turned down, the legal end of the road.

So the bottom line is this: The vast majority of the cases filed with the court are disposed of without any justice laying eyes on the legal papers that set out the reasons for the court to take the case.

"Selecting 100 or so cases from the pool of 6,000 petitions is just too important to invest in very smart but brand-new lawyers," onetime Burger clerk Kenneth Starr, now the Whitewater independent counsel, wrote in 1993. Starr says that by ceding screening to the clerks, the court has ignored business cases that might seem boring to clerks, but crucial to commerce.

Recently, the court declined to review a case that posed a key procedural issue in bankruptcy law. In his lower court ruling in the case, Appeals Judge Richard Posner took the rare step of explicitly urging the Supreme Court to review the case. Conflicting rulings by other courts on the same issue, Posner said, had created a confusing split that "only the Supreme Court can heal."

The court turned down the invitation. Posner declines to ascribe the rejection to law clerks, though he does agree with Starr that "there seems to be a bias in favor of non-commercial cases" at the court.

Again, justices and most clerks insist that in spite of the clerks' crucial role, strong incentives are at work to prevent clerks from abusing their power. Justices who find a pool summary intriguing will often ask their own clerks to study the case further, or the justices themselves look at the briefs. Some justices' clerks routinely add their own research to the pool memo. Any clerk found to have shaded a summary to achieve a particular result -- to protect it from review or promote it -- would be embarrassed or fired, defenders of the system say.

"You're in perpetual fear of making a mistake," says ex-clerk Laura Ingraham. "The fear factor keeps the work product reliable."

Pushing fewer cases

Fear also plays a role in another major impact the clerks have had on the work of the court. The court in the last two terms has decided roughly half the number of cases it decided in the early 1980s. A wide range of explanations has been offered.

Justice Stevens, for the first time, says the clerks may be responsible.

With more justices sharing the clerks' pool memos, Stevens says, the clerks have become increasingly cautious in recommending that the court take up a particular case.

"You stick your neck out as a clerk when you recommend to grant a case," says Stevens. "The risk-averse thing to do is to recommend not to take a case. I think it accounts for the lessening of the docket."

Asked if he thinks the clerk pool should be scrapped, Stevens shrugs. "If I made all the rules, I don't think I'd want it," he says.

Sometimes at the nation's highest court, keeping a case off the docket can make the difference between life and death. The court is now filled with capital punishment supporters. But when it was more closely divided, the vote of one justice could decide whether a condemned inmate lived or died.

Justice Lewis Powell often was the swing vote on taking death cases, says Vanderbilt law professor Rebecca Brown, a clerk in the late 1970s. "He would want to be persuaded on the merits. Some clerks were more inclined to make the case (against execution) to him than others. It might have made the difference."

The forthcoming book by Lazarus, in one of its most serious charges, says the clerks' life-or-death power continued through the late 1980s. He claims Justice Kennedy, often a swing vote on capital punishment cases, could be swayed to vote against delaying executions by playing up procedural flaws and getting him to vote before it became clear that his vote would be decisive.

Lazarus says a group of conservative clerks "considered expediting executions a central part of their collective mission, and they pursued that goal passionately."

When serial killer Ted Bundy was executed in 1989, Lazarus says, conservative clerks broke out a bottle of champagne to celebrate. Several clerks mentioned in the book declined to comment publicly, but said Lazarus' charge is inaccurate.

That pro-execution zeal, if it ever was present, has faded. More recent clerks describe screening last-minute death row appeals as the most awesome responsibility they have.

"The papers come in late at night, when the justices are not in the building. You have a few minutes to decide whether there is enough merit in an appeal to really push a case," says a clerk from last term who asked not to be named. "It's very difficult at 2 a.m."

Though the court never discusses its handling of death row appeals, it is agreed that law clerks review the issues raised by the inmates and then phone or fax their justice for a vote. One clerk recalls awakening Justice Sandra Day O'Connor three times in a single night on a death row appeal.

Timid ghost writers

To some critics, the fact that the law clerks screen the cases is not as troubling as the role they play in writing the court's decisions. Though each of the nine justices operates differently, insiders say that eight justices -- all but Stevens -- rely on their clerks for the first drafts of some or most of their opinions.

"Part of the reason I do first drafts myself is for self-discipline," says Stevens. "I don't really understand a case until I write it out."

But even Stevens turned over some of the writing of his Internet decision to his clerks during a particularly busy period last term. His clerks and others, many of them Internet whizzes, took an unusual interest in the decision, which gave broad First Amendment protection to the new medium. The court's library arranged for a demonstration of the Internet, and several clerks eagerly showed their justices how to navigate the network.

Just about anyone who has written a business report or term paper knows that the person who writes a first draft has enormous influence over the final product.

Could that influence be exerted with political motives? During the late 1980s, stories circulated about a "cabal" of conservative law clerks who tried to steer their justices toward rigid anti-abortion opinions in pending cases. The existence of the group polarized the clerks, according to Lazarus, who tells of a shoving match between an O'Connor clerk and a Brennan clerk.

In July 1989, the court handed down the Webster vs. Reproductive Health Services decision, which upheld a Missouri law restricting abortions. It was a major defeat for those who favored abortion rights, engineered in large part by conservative law clerks, according to Lazarus.

The "cabal" ultimately disbanded, and more recent clerks say that political cliques are a much-discouraged thing of the past.

A clerk's ideology is still a factor, some clerks say. "Justice Scalia considers it," says 1997 clerk John Fee. "But he likes to have clerks with a variety of perspectives."

The current justices use their clerks in a wide range of ways for opinion-writing. It is a violation of etiquette for clerks to boast that their first drafts emerged from the court virtually untouched, but some say it happens.

Justice Stephen Breyer reputedly tears apart most of a clerk's first draft, often leaving none of it undisturbed. Souter writes significant parts of many of his opinions in longhand -- no word processor in his chambers yet. Scalia's sarcastic wit shines through many of his opinions, and he sometimes writes first drafts, too.

Yet all three also make considerable use of their clerks' first drafts. And Rehnquist, O'Connor, Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Clarence Thomas are said to give their clerks free rein with first drafts fairly often.

The effect of the clerks' authorship is difficult to quantify. But an increasing number of scholars say that in the last decade, because of the clerks, the court's opinions have become more timid and turgid, lengthier and full of partial concurrences and complex balancing tests.

Last term, the court produced 192 opinions, including concurrences and dissents, in 86 cases. That's nearly twice the number of writings per case than 50 years ago.

"Except when Scalia is having a tantrum, no justice writes anything memorable anymore," says Domnarski, the author. "It's the law review style -- the passive voice, nobody wanting to assert anything."

Yale's Kronman, in a recent book, The Lost Lawyer, decries the "law clerk revolution" for similar reasons.

"Opinions written by law clerks tend to be longer because their authors have not yet acquired the conciseness that comes with experience and practice," he writes. "Being new to the law, moreover, they lack confidence in their own insight and judgment, and therefore tend to include every conceivable argument for their position."

Landmark opinions such as Roe vs. Wade, which declared women's right to abortions in 1973, tend to be written by the justices.

"Justice Blackmun wrote Roe from the heart. The little beasts don't have them," says University of Virginia law professor Pamela Karlan, referring to law clerks. Karlan was a Blackmun clerk herself.

The writing itself matters because opinions of the Supreme Court are not ephemeral, like the speeches of a member of Congress or a newspaper or magazine article. Supreme Court rulings are studied for decades, their words parsed and interpreted by lower courts for longer than that.

"In the broad sweep of the law, the effect of clerks is negligible," says Michael Dorf, a former clerk for Kennedy and a constitutional law professor at Columbia University. "But it is true that, sometimes, you will see lower courts deciding a case, basing a decision on their interpretation of a phrase that was written by a clerk."

One clerk-authored footnote has caused controversy since it was written in 1954. The court's forceful opinion in Brown vs. Board Education struck down school segregation; the footnote, for the first time, cited social science findings as proof that segregation was harmful to black children. Conservatives attacked the footnote as introducing a factor that the court should not have considered.

But now, the clerks write far more than footnotes. And the more these rulings end up sounding like law school papers, some scholars fear, the less respect they will gain or deserve, and the harder they will be for judges, and citizens, to interpret.

"For the law, it is a disaster, since it will inevitably lead not only to a dilution in the quality but also in the reputation of the court," University of Tulsa law professor Bernard Schwartz wrote before he died last year. Schwartz, author of more than 60 books on the court and the law, was a persistent critic of the law clerk phenomenon, blaming the growing reliance on clerks for the "mediocrity" of the current court.

Others counter that neither the president nor members of Congress are the authors of most of what they say or write, either. The other branches haven't suffered, defenders say, and the Supreme Court should not be held to a different standard.

Ronald Klain, a former clerk for Justice Byron White who has had key jobs in all three branches of government, he agrees with that defense -- to a point.

Now chief of staff for Vice President Gore and formerly counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Klain says, "Supreme Court law clerks have less impact on the Supreme Court than do the staff of Congress and the White House. The difference is that the law clerks are so young and inexperienced. The fact that any power at all is vested in someone who is one or two years out of law school is incredible."

Findings

Of the 394 clerks hired by current justices, just:

1.8% were black

1% Hispanic

4.5% Asian

24.3% women

Four justices have never hired a black law clerk.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Supreme Court law clerk's growing influence affects case rulings