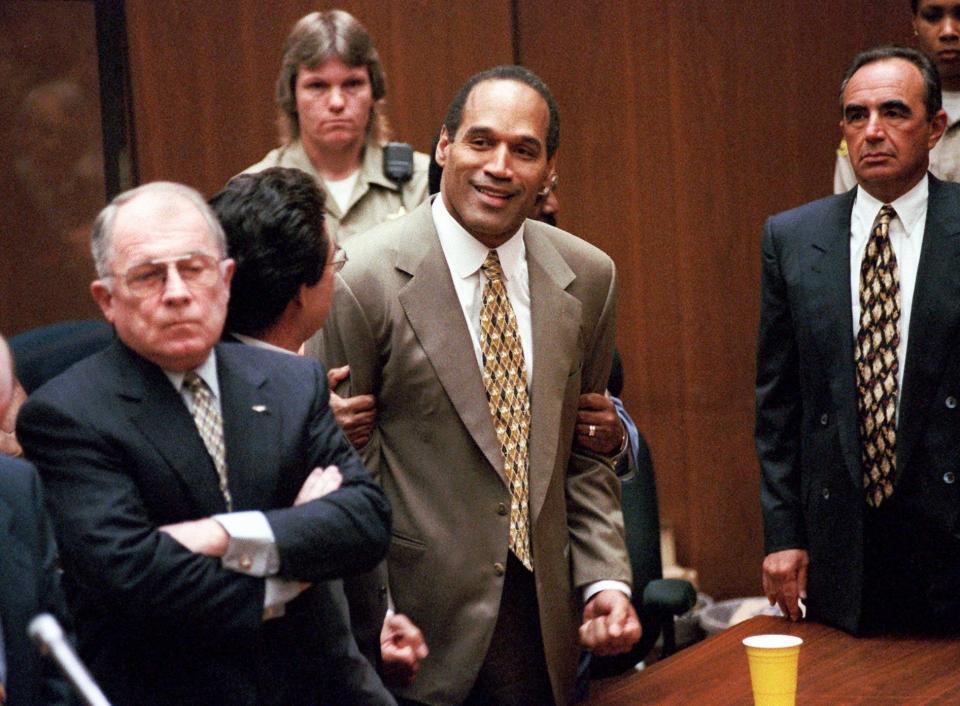

From the archives | Simpson free: Prosecutors 'ran from their evidence'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story originally published on Oct. 4, 1995. It is being republished as part of the commemoration of USA TODAY's 40th anniversary on Sept. 15, 2022.

The defense never rested. And the prosecution never woke up.

In the search to explain Tuesday's verdict in the trial of the century, what emerges is that in the O.J. Simpson trial the traditional roles of prosecution and defense were reversed.

The prosecution, which is supposed to bear the burden of proof, to lay out the evidence in an orderly and logical way to a receptive jury, instead collapsed under the burden of missing evidence, lost opportunities and a defense assault that seized the momentum from day one of the trial.

The defense, for its part, relentlessly struck the theme of Los Angeles police incompetence and racism - a ploy that apparently resonated with the mostly black jury. The defense never let an unrefuted piece of evidence gather dust, ramming the prosecution daily with charges and new revelations that always demanded a response.

Add to that a jury that seemed ready, even eager, to reject the prosecution's theory for racial or evidentiary reasons, and the not guilty verdicts -- at least in retrospect -- seem obvious.

"I don't think that Clarence Darrow in his best days could have gotten a conviction," says former prosecutor Henry Hudson. "The prosecution had to defend itself constantly, and the defense was successful in creating the illusion of innocence":

-- The gloves didn't fit.

-- Mark Fuhrman, a witness the prosecution embraced, turned out to be a racist - and a liar.

-- Simpson's blood may have been planted on the sock - and the prosecution never rebutted that suspicion successfully.

-- The prosecution's timeline did not fit - and even the re-read testimony of limousine driver Allan Park did not make it hang together.

Prosecutors, pegging the time of death to the wailing bark of Nicole Simpson's dog, said Simpson had at least 30 minutes to murder before he returned to catch an airport limousine. But defense witnesses - ordinary citizens who had volunteered their services but were disdained by the prosecution - pushed the dog's barking back 15 minutes, cutting the timeline close.

Then defense expert Michael Baden, one of the nation's leading pathologists, testified the murders were preceded by a vicious death struggle lasting up to 15 minutes. Prosecutors scrambled to draw a new timeline, but it was too late.

-- Police and prosecution practices that would not have raised a ripple in most cases were nitpicked by the defense. Police threw a hair-strewn blanket over Nicole Simpson's body, casting doubt on the trace evidence. The coroner wasn't called in for 10 hours, making the time of death suspect. Deputy Irwin Golden failed to perform routine autopsy procedures.

"The prosecution ran from their evidence and went down every blind alley the defense took them down," says prominent defense lawyer William Moffitt. "They lost the one thing you need to go to the jury with - their belief in you."

None of the prosecution's evidence – not even the supposedly ironclad DNA evidence – was allowed to linger unchallenged in the minds of the jurors. Barry Scheck, possibly the brightest star of the defense team, hammered away at the sloppy work of the police labs, aided by star witness Dr. John Gerdes. The doubts he raised were never effectively rebutted.

"If you take the DNA evidence away, all the jury was left with was two gruesomely murdered bodies and a barking dog," says Southwestern University law professor Myrna Raeder. When all was said and done, the Simpson murder trial was a circumstantial evidence case – the murder weapon was never found, and no human witnesses ever came forward.

Even during the closing arguments of prosecutor Marcia Clark, the defense did not let up, objecting nearly 60 times.

The objections were dismissed, but they continued to telegraph the message to the jury: The defense is in charge here.

To hear defense lawyer Robert Shapiro tell it, that strategy of questioning all the evidence was conceived hours after Simpson was arrested.

"The single best move I made was making that call to Dr. Henry Lee on June 13, 1994," says Shapiro. "And we didn't just benefit from his testimony. That was a small part. It was for everything he told us to do the whole way through."

Lee looked at every piece of evidence in the case, Shapiro says, and coached the defense on what to question.

The prosecution was left reeling, unable to achieve its primary duty: to turn a chaotic night of crime and disparate pieces of evidence into a single story with a beginning, middle and an end that appeals to the common sense of a jury.

Johnnie Cochran's final mantra to the jury exploited the prosecution's stumbles: "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

Another strategic victory for the defense came even before the trial began, when jury consultant Jo-Ellan Dimitrius pored over the questionnaires of potential jurors and helped the defense team pick a jury well-suited for a police brutality case.

The prosecution's approach to jury selection may also have sealed its doom from the outset.

Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden pointedly refused to winnow blacks out of the racially mixed pool, though experts - including their own jury consultant - warned that some were hopelessly biased in Simpson's favor. Prosecutors left 10 peremptory challenges unused.

District Attorney Gil Garcetti also took a gamble on a downtown Los Angeles jury, though he was faced with almost certain censure if he had tried the case in the predominantly white Santa Monica district where the murders took place.

As the trial proceeded, both prosecution and defense chose targets that went beyond the night of the double murder.

The prosecution focused on Simpson's prior abuse of Nicole, and the defense played the race card, especially once the taped evidence of Fuhrman's racial slurs landed in its lap.

In the end, the prosecution's diversionary tactic proved to be a blunder, and prosecutors jettisoned it as the trial wore on. A videotape of a smiling Simpson embracing Nicole's family the evening of the murders undercut the angry picture prosecutors tried to paint of the defendant.

"The prosecution started this case with evidence of domestic violence to prove motive, before presenting the evidence" of the murder, says UCLA law professor Peter Arenella. "That might have created the impression in jurors' minds that the prosecution was trying to assassinate Simpson's character."

But the prosecution carried on, backing up its DNA tests with more traditional circumstantial evidence, including shoeprints Simpson's size, carpet fibers resembling the floor of his Bronco and hairs consistent with his type. The prosecutors' argument: No combination of corruption and contamination could have produced such overwhelming evidence, all pointing toward O.J. Simpson.

The tape of Nicole Brown Simpson's anguished 1993 call to police after her ex-husband broke down her door let the murder victim speak directly to the jury from the grave, analysts say. Also powerful: the photographs of her bruised face and arm and the will she left in a safety deposit box, they add.

That evidence crumbled nonetheless, perhaps most of all because of the credibility and race problems Fuhrman caused. Just how important Fuhrman and the race issue were to the case will be debated long and hard - even after the jurors speak out. The prosecution's defenders say the race issue blinded the jurors to the evidence.

"I've never seen a more obvious case of guilt," says Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted Charles Manson. "Yet this jury apparently gave no weight to the mountain of incriminating evidence and instead bought into the defense argument this was a case about race. And it was their opportunity to rectify and put an end to centuries of racism by the white community."

Fuhrman posed the biggest dilemma for the prosecution. After relying heavily on him in the beginning of the trial, it would have been awkward to completely repudiate him once he was discredited. Prosecutors distanced themselves from Fuhrman, but may not have made it clear enough that their case was still strong without him. Fuhrman's damage was irreversible.

"If the jury doesn't like the main character, they're not going to like the play," says jury consultant Robert Hirschhorn.

"This was a total repudiation of the LAPD and the prosecution for wrapping itself in the LAPD," says Harland Braun, one of the defense lawyers for police charged in the Rodney King beating case.

The other defense advantage - shared by few others accused of murder - was money. The defense team doesn't deny it. Their strategy might have been brilliant, but it would have remained on the drawing board without Simpson's millions to bring it to life.

"What this verdict tells you," says Arenella, "is that the quality of justice depends on how much money you spend to hire the best lawyers, and how much you can match the power of the state by sewing up the best experts to fight."

Contributing: Gale Holland, Richard Price and Sally Ann Stewart

USA TODAY/CNN/GALLUP POLL What would the verdict have been if Simpson were... White

Guilty 41%

Not guilty 45%

Not rich

Guilty 73%

Not guilty 19%

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: O.J. Simpson found not guilty due to prosecution's missing evidence