Arizona author charts a course through 1930s science and sexism on the Colorado River

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

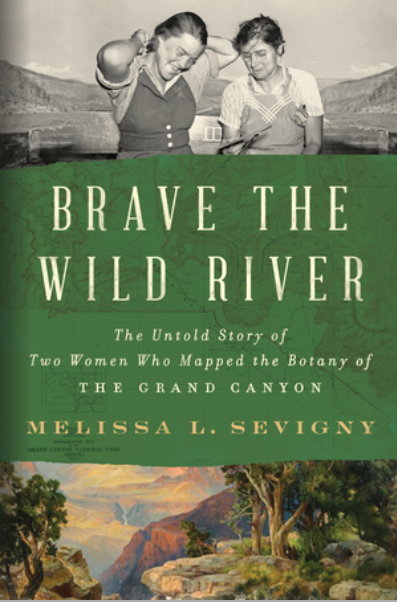

Melissa Sevigny's new book, published Tuesday, will make readers yearn for the adventure and natural beauty of a Colorado River rafting trip at the same time that it fires them up over sexism in science and media.

Drawing on the detailed diaries of two botanists who became the first white women to "Brave the Wild River," as the book is titled, the Flagstaff-based author guides us through the rough waters and peaceful moments of a story about facing fears and bucking norms to pursue scientific passions for the benefit of future generations.

At a time when the Colorado River is making headlines like never before, due to drought conditions and tense negotiations between states over dividing up the fluctuating water supply, Sevigny takes us back.

Back before the Colorado River Basin's water needs for agriculture and a growing population exceeded its flows. Back before the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam and the existence of Lake Powell. Back before scientists worried much about how that dam would affect the Grand Canyon ecosystem. Back even before the term "ecosystem" was in common use, but when two Michigan-based botanists nevertheless understood the value of documenting the species of plants eking out a living in this harsh and turbulent river corridor.

The story Sevigny tells takes place mostly in 1938, when an unlikely crew of two female scientists new to river trips joined forces with a would-be commercial boater determined to invent that industry and a rotating cast of oarsmen trying their luck through seldom-run rapids. They built their own boats out of wood and screws, cooked their own meals (the women were expected to do that) and scouted their own rapids in rocky waters known to have claimed the lives of white adventurers who had tried before. (Sevigny is careful to note throughout the book that the Indigenous peoples who call the region home were the first to accomplish many of the feats later hailed as novel achievements by white explorers.)

The 43-day-long summer journey featured sweltering temperatures, group discord and a range of mishaps including a runaway boat and some unintentional swimming. All along the way, the women "worked well past sundown," Sevigny writes, to document — via their journals and plant vouchers — how the botany changed as they progressed down river, filleting cactus pads and scooping out sticky flesh to press the spiky remains between sheets of newspaper for transport to herbaria collections. They slept on flat rocks in homemade bedrolls along the river banks, then woke before the rest of the crew to prepare breakfast for them daily, "moving quietly among their sleeping companions and fumbling at the dishware with cold fingers while dawn pinked the tops of the cliffs and painted them blush and rouge."

The hard work of career scientists Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter went largely unrecognized by the journalists who covered the expedition at the time. Most accounts failed to even mention the word 'botany' or acknowledge the research merits of the trip, framing it instead as a thrill-seeking jaunt these reckless women had no business participating in.

As a science journalist herself stepping into the story 85 years later, Sevigny rights this wrong. By relying on the journals and scientific legacies left by these women, she reframes the story, often in their own words.

The 257-page account is one of two courageous and dedicated botanists who overcame their own fears and the many sexist barriers that 1930s society had constructed for career-oriented women. These two individuals were willing to trade ruffled skirts for overalls and decorum for scientific achievement and produced, as a result, ecological findings of lasting value.

"There was simply no other comprehensive plant list published prior to the closure of Glen Canyon Dam," Sevigny writes. "Anyone who wanted to understand how the vegetation had changed — because of dams, exotic species, or any of the other human and natural influences at work on ecosystems in the past half-century — had to refer to Clover and Jotter's work."

More: As climate disasters force people to flee, a new book examines the modern migrant quandary

Change on the river is a theme of the book. Since the construction of Glen Canyon Dam in the 1960s, environmental activists have mourned the drowning of sites upstream as well as the loss of sediment carried by a natural flood cycle that once built up beaches downstream and created habitat for native plants and wildlife. The flora has changed as a result, with invasive species filling in the new, more calm spaces where only plants that could reestablish after chaotic floods existed before.

Climate change, too, is taking a toll on the river by redefining which plants and animals can survive in these places with rising temperatures and a decades-deep drought.

River rafting culture has changed swiftly. In 1938, the Grand Canyon National Park discouraged travel by river, not wanting to spend resources on rescue efforts. Now rafting the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon is a major commercial endeavor and a hallmark of the park experience for adventurous tourists (though modern rafting trips have luxuries Clover and Jotter could not have imagined). River runners no longer paint their names on the rock walls of the canyon, but the environment is forever changed by the modern impact of 27,000 annual rafters.

Read the climate series: The latest from Joan Meiners at azcentral, a column on climate change that publishes weekly

The book also highlights aspects of the 1938 trip that remain woefully unchanged. Many of the undertones of sexism in science and outdoor exploration Sevigny chronicled echo situations still experienced by female researchers and adventurers today. Clover and Jotter felt that their work was not taken seriously in their time. Female scientists today receive less recognition for their work than their male colleagues, as evidenced by fewer authorship opportunities and lower citation rates for the same type of work. Sexual harassment is also still a major concern for women working in national parks though, thankfully, that was not something the 1938 botanists dealt with.

Overall, the book's tone is triumphant, celebrating the adventurous spirits and scientific accomplishments of these women and their companions. It's a story so relevant to modern discussions about water resources, climate change, science, sexism and the impacts of recreation as to likely feel shocking to many readers that they have not heard much about these trailblazers before.

By telling the tale of the 1938 expedition now, Sevigny brings to light many important themes of the modern era that will be relevant discussion points in ecosystem management for years to come. With experience as a poet, she also artfully bridges a gap of nearly 100 years to shape the timeless story of a shared human experience with nature.

"What does 'wild' mean, anyway?" Sevigny asks in the final chapter. "Not untouched by human presence, for even the plants — especially the plants — show how the canyonland's first inhabitants tended agave and prickly pear, coaxing them into new shapes. A wild place isn't one unchanged by humans. It's a place that changes us."

Joan Meiners is the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com. Read more of her coverage at environment.azcentral.com.

Support climate coverage and local journalism by subscribing to azcentral.com at this link.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: "Brave the Wild River" takes us down the Colorado River of 1938