Arizona was a holdout about honoring Martin Luther King Jr. Here's what it cost the state 30 years ago

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Gene Blue hopes the millions of Arizonans who won't attend work or school due to Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the state Monday take pride in the struggle that culminated with making it a reality 30 years ago.

In the fast-growing state — the only one in the country to enact the holiday by popular vote — many likely are unfamiliar with the history.

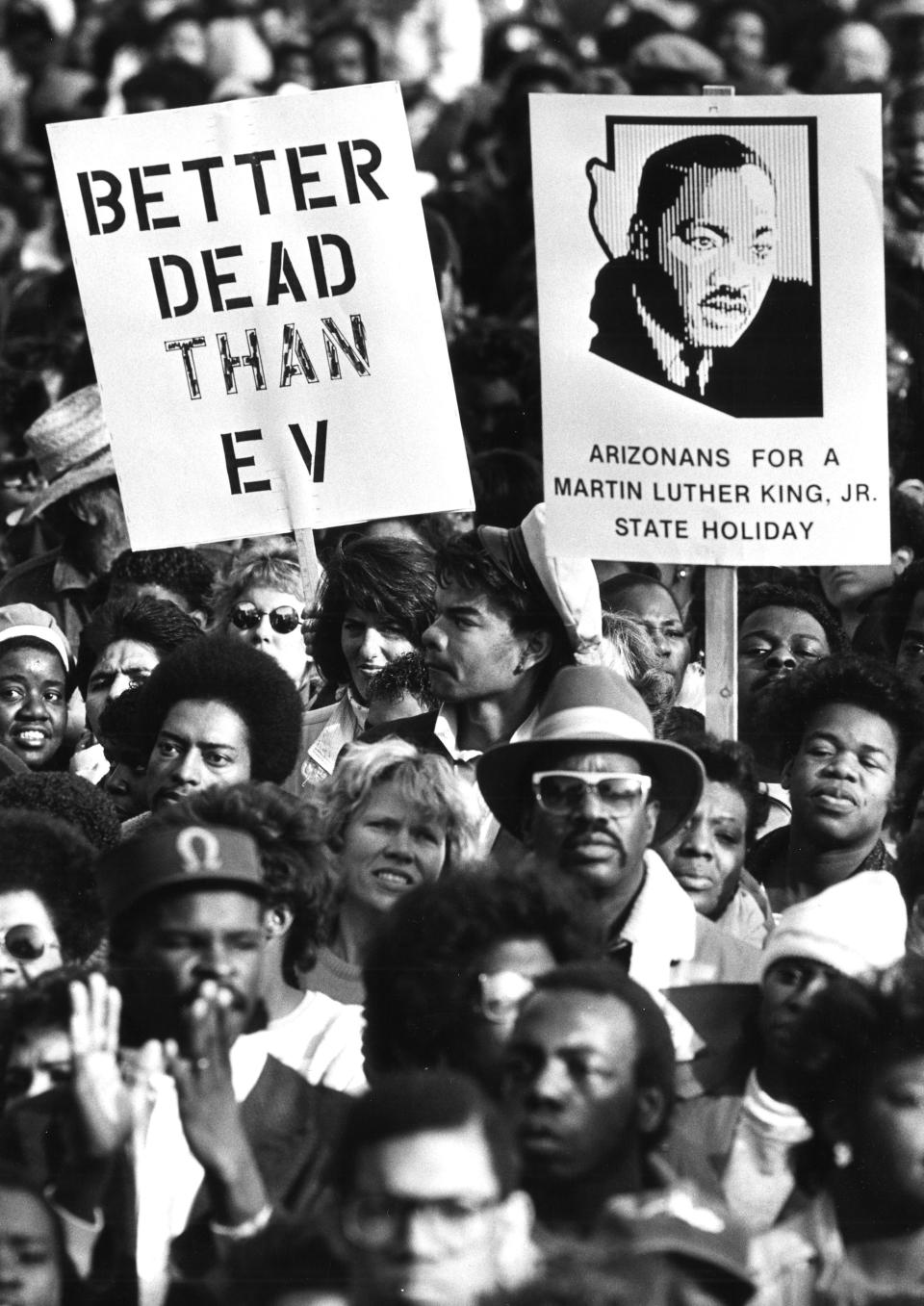

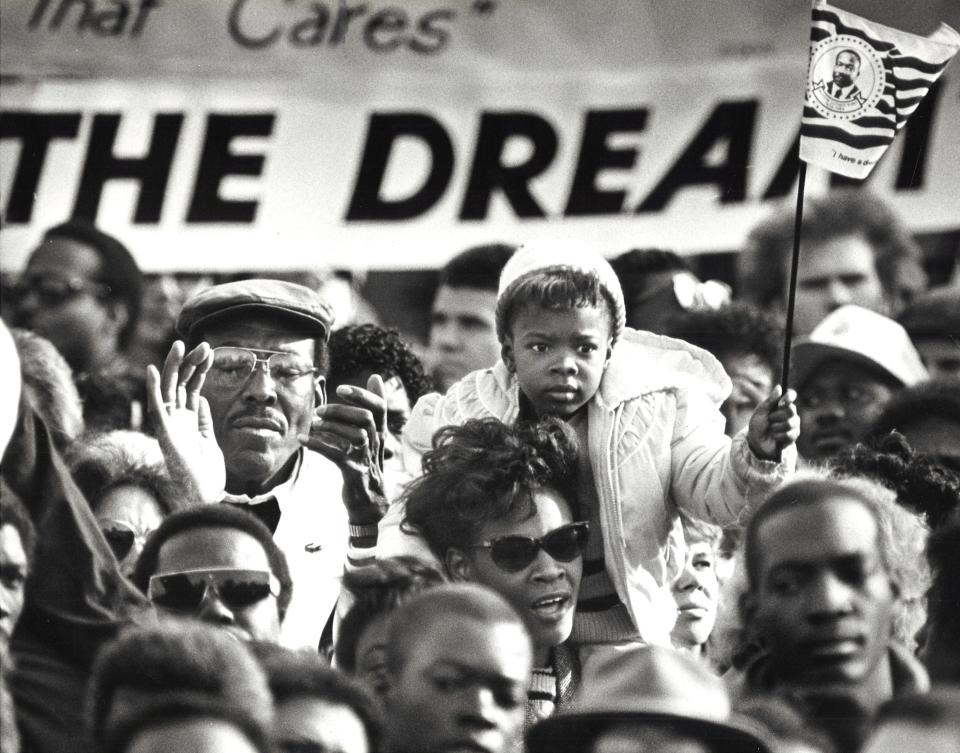

“It took collective energy to make this happen,” said Blue, who has chaired or co-chaired the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration Committee for the past 37 years. Blue, 83, organized many of the marches that became an important part of the effort to create the holiday. “We need to continue to educate about what we went through as a people, peacefully, to obtain this holiday.”

Monday's holiday marks three decades since Arizona celebrated its first MLK Day. This year also marks 30 years since Arizona missed out on its first Super Bowl, which the NFL moved to Pasadena after voters rejected the holiday. The pullout caused an estimated $200 million to $500 million in economic loss.

Arizona is preparing to host its fourth Super Bowl on Feb. 12 at State Farm Stadium in Glendale.

Yet as recently as last year, some Black Americans still believed Arizona wasn't a worthy location for the event.

In January 2022, about 200 pastors from Arizona and around the country sent a letter to the National Football League, asking it to once again deny Arizona the Super Bowl. This time, the letter outlined, the main problem was election bills the state Legislature passed in 2021 that "harmed" minority and low-income voters. The pastors also were angry with Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz., for voting against the "Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act" and a federal minimum wage.

The pastors didn't continue their collective effort to pressure the NFL, but Black leaders and others who took part in the effort to make MLK Day a reality in Arizona say there is still work to do in the state

MLK Day had foe in former Gov. Mecham

Multiple cities and towns across the U.S. began honoring the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. soon after his assassination in 1968. Former President Ronald Reagan declared a federal holiday for the civil rights leader in 1983; it was enacted in 1986.

State lawmakers in the 1970s, including Cloves Campbell, Arizona’s first Black senator, Sen. Manuel “Lito” Peña and House Minority Leader Art Hamilton, took up the fight early introducing bills for a holiday that found no traction among the mostly white, male Legislature.

Arizona was not the last state to create an official, paid MLK holiday, but was perhaps the most well-known of the holdouts because of the resistance of former Gov. Evan Mecham.

Mecham, a Republican automobile dealer who won the three-way 1986 governor’s race with less than 50% of the vote, denied he was racist during his short time in office, but there’s little question that he talked like one. He infamously defended a slur to describe Black children and was known nationwide for his bizarre and politically incorrect comments.

On Jan. 12, 1987, in one of his first actions after taking office, he rescinded a 1986 executive order by previous Gov. Bruce Babbitt, a Democrat, to create the holiday after the Legislature failed to pass it by one vote.

Mecham's new executive order stated the Legislature, not the governor, had the power to create a state holiday. Whether legally sound or not, the move outraged people across the country and led to boycotts by entertainers Steve Wonder and Public Enemy, as well as many corporate conventions. Economists estimated the state lost more than $200 million over the next two years.

A little over a year later, in April 1988, the state Senate impeached Mecham on charges of misusing state funds and obstruction of justice. But he continued his fight against the holiday while out of office.

That year was also when Arizona, which had half the population it does now, landed its first NFL team, the Cardinals, who moved from St. Louis. Business leaders looked forward to seeing the state host its first Super Bowl and were told that securing the event would depend on Arizona recognizing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a state holiday.

Republicans in the Legislature, many of whom were not Mecham fans, warmed to the idea and passed a bill in late 1989 in a special session ordered by the governor who replaced Mecham, Democrat Rose Mofford. The bill would have replaced Columbus Day with MLK Day, which angered Italian Americans.

That March, Mofford and other Super Bowl advocates lobbied the NFL for three days during a league meeting in Orlando. Negotiations ended with the NFL choosing Arizona for the 1993 Super Bowl. Business leaders rejoiced at the news. But the chair of the NFL’s Super Bowl selection committee, then Philadelphia Eagles owner Norm Braman, told the press covering the decision: “You have to get the Martin Luther King problem straightened out or you won’t have the game. If that situation blows up in Arizona and there is a smear of any kind, I will personally lead the effort to rescind the Super Bowl game. … How could we go there?”

The situation blows up and the NFL bows out

Mecham, his followers, and members of the Arizona American Italian Club collected enough signatures to put the new law up for approval by voters on the November 1990 ballot.

“It was horrible,” said Sandra Kennedy, a former long-time lawmaker and member of the Arizona Corporation Commission. “It was almost as if it was pitting one community against the other. Wow. And that is not what, you know, we were trying to do.”

Mofford and the Legislature responded with a new law to block the vote on the Columbus Day law and create a separate holiday for MLK Day. Mecham and the holiday foes collected enough signatures to put that one on the ballot, too. The Italian-American group supported the second law.

Mecham claimed that enacting the holiday would be “reverse discrimination against white people who don’t want (it).”

Tensions grew in Arizona cities as the November election grew closer, newspaper reports at the time show, with the pros and cons debated around office water coolers and in homes.

By that year, Phoenix, Tucson and several other Arizona cities were already giving their employees the day off. But some Arizonans were reportedly concerned about the price of a state holiday, which at the time would have cost $500,000 for all state employees — a pittance compared to the consequences to come.

Other voters claimed they were incensed at the NFL’s threat. Racism among some voters likely was also an issue, newspapers reported at the time.

Voters rejected both laws passed by the Legislature, sparking a new round of boycotts. As promised, the NFL canceled the 1993 Super Bowl in Arizona, which was to be played at Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, and moved it to the Rose Bowl in California.

Braman told The Arizona Republic in an interview Thursday that the reason was the “obvious disrespect” the state had shown to Martin Luther King Jr. and the fact that the NFL had a “preponderance of African-American players.”

“It was the right thing to do, but I'd be less than candid if I didn't say it wasn't painful,” the Miami billionaire said. “I mean, I received death threats and I had security after that when I went to Arizona.”

Backers of holiday finally secure victory

Supporters of the holiday were undeterred.

They began collecting signatures for a new ballot initiative in 1992, but the Legislature beat them to it. The new plan combined the George Washington and Abraham Lincoln holidays into one, allowing the state to add another holiday — keeping the total number of state holidays at 10 — without extra cost.

The ballot measure received endorsements from prominent Republicans including Reagan and Fife Symington, who won the election for governor in 1990 after Mofford decided not to run.

It passed overwhelmingly, 61% to 39%, that November.

A few weeks later, on Monday, Jan. 18, 1993, Arizona celebrated its first official MLK Day holiday as a state. Thousands of people marched in Phoenix and festivities included appearances by Stevie Wonder and Rosa Parks.

Kennedy told The Republic she still has bittersweet feelings over what happened.

"It saddens me that it took a vote to get the holiday when the Legislature could have been the saving grace or the savior in passing a bill to create the holiday," she said.

Symington said the state has "nothing to be embarrassed about" over its MLK Day history. While he lauds the results of that year's election, he said the NFL threat was "certainly one reason" the other 1990 measures failed. He doesn't think the Super Bowl should have been involved, saying that mixing politics and sporting events only creates a "mess."

Leaders don't want it to be 'just another holiday'

Before the 1992 vote on the ballot measure, Symington said he received confirmation from Paul Tagliabue, then the NFL commissioner, that Arizona would get a Super Bowl if it passed.

"He was a man of his word," Symington said.

The state hosted its first Super Bowl in 1996, and two more followed in 2008 and 2015. The latter brought an estimated $719 million in revenue to the state, according to the L. William Seidman Research Institute at Arizona State University.

Former Rep. Art Hamilton, who served from 1973 to 1999 in the state House of Representatives and was a key player in pushing for the holiday over the years, said in 1989 the holiday still would be worthwhile only if the homeless and helpless were remembered, and it doesn’t become “just another three-day weekend.”

On Friday, before the award ceremony in Phoenix, Hamilton said nothing's perfect, but victories like the MLK holiday are "worth it."

"We sometimes are reluctant to tell young people the work that remains — it shows we didn't get everything done," Hamilton said.

Monica Tipton, chair of the MLK committee's Community Days of Service division, which distributes meals in low-income neighborhoods, said that "sadly, I think it's becoming just another holiday." She hopes to see more young people involved in the celebratory events.

"Having more of the younger generation, the millennials, involved in planning, so that we can be more progressive is extremely important," she said. "We also need to be present so that they understand the history."

Reach the reporter at rstern@arizonarepublic.com or 480-276-3237. Follow him on Twitter @raystern.

Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 30 years ago, Arizona was a MLK holiday holdout. Here's why