Arizona kids are losing their lives to counterfeit pills containing fentanyl

At 17, Kaylie Tallant had big dreams — the San Tan Valley high school student talked about one day going to Penn State and studying law, or maybe going into health care like her mom.

While school and friends consumed most of her time, she liked using free moments to watch "Grey’s Anatomy," "Gilmore Girls" and "Pretty Little Liars." Painting with watercolors was her creative outlet. She enjoyed abstract art and experimenting with colors that reflected the way she was feeling.

Kaylie, who was supposed to graduate from high school in 2021, is one of 2,006 Arizona residents of all ages whose deaths were classified as being caused by an opioid overdose that year. That's the highest annual number of fatal opioid overdoses reported in Arizona since the state began collecting such data.

"My daughter didn't go to parties. Her friends came to my house because that's what I thought I had to do to keep her safe. ... Never did I ever, ever, ever think it was any type of pill," said Kaylie's mother, Misty Terrigino, who discovered her daughter's body on April 12, 2021.

"It was not until I got the toxicology report six weeks later that I found out she had street fentanyl in her body."

Kaylie’s autopsy report says her death was accidental and due to "fentanyl toxicity."

Fentanyl, which is a potent, cheap and highly addictive synthetic opioid, is driving a majority of opioid overdose deaths in the U.S. and in Arizona, public health data shows.

Children are especially vulnerable to illicit fentanyl: In 2020, the number of infants, kids and adolescents ages 17 and younger who died because of fentanyl rose to nearly five times the number who died in 2018, data from the state's Child Fatality Review team shows.

Along with a proliferation of fentanyl in Arizona, the pandemic and social media may be partly to blame for that spike.

It's unclear whether 2020 was an outlier for kids and opioids. Preliminary state data indicates the number of kids who overdosed and died from opioids, including fentanyl, declined in 2021 yetstill was above the 2019 death tally. There's often a delay in reporting final overdose statistics.

Counterfeit pills that appear to be made by pharmaceutical companies remain ubiquitous in Arizona.

Round blue pills mimicking 30 milligram oxycodone pills are among the most common, but they've turned up in a range of shapes, colors and forms, federal law enforcement officials say.

The pills often contain fentanyl in varying doses, and those doses can be lethal. Some Arizona teens are purchasing fake pills believing they are prescription drugs such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin and Xanax, for as little as $1 to $5 each, but not knowing they contain fentanyl.

Prevention: 2 women indicted after deputies find more than 850,000 fentanyl pills

Fentanyl is not just showing up in phony opioids and benzodiazepines — it has been found in counterfeit pills meant to look like stimulants such as Adderall.

Officials with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration caution that the only safe medications are the ones prescribed by a trusted medical professional and dispensed by a licensed pharmacist.

Kids are sometimes finding the pills through people they meet on social media sites such as Snapchat, TikTok and Instagram, which is why the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration developed an emoji decoder tool to help parents understand some of the symbols that drug traffickers commonly use with kids on social media.

"That's the scariest thing for me. I have a teenage son and I am constantly looking at his social media. ... I don't want him to make a tragic mistake," said Cheri Oz, special agent in charge of the DEA's Phoenix field division.

"Any pill you buy illicitly is not a safe pill."

It takes just a small amount of fentanyl to cause someone to die. And with no quality control on illicitly manufactured pills, one pill might have two milligrams of fentanyl or 10 milligrams, there's no way of knowing, Oz said.

"We have story after story of kids just being tricked or fooled, and they don't get a second chance," Oz said.

Mom: It was fentanyl poisoning, not an overdose

Kaylie's family does not think the word overdose applies to the way she died. Echoing the sentiments of many other parents around the country whose kids have died from fentanyl, Kaylie's mother says her daughter died because of an accidental fentanyl poisoning rather than an overdose.

"It's not just a stigma thing. Our kids did not willingly ingest fentanyl," Terrigino said. "They are taking a pill that is stamped and pressed to resemble that of a pharmaceutical pill."

Another reason why some families prefer "poisoning" is that kids are often dying after ingesting one or two pills. Even two milligrams of fentanyl can be enough to kill, depending on the person, Oz said.

"We have parents that have lost children with two milligrams of fentanyl because it was an opioid-naive person taking one pill one time," Oz said.

The DEA's campaign to raise awareness about counterfeit pills containing fentanyl is called “One Pill Can Kill.”

Oz keeps the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone (often known by the brand name Narcan) in her family's home as a safety precaution.

"I'm a DEA agent. My husband's a DEA agent. Our kids have been hearing about drugs since they were in utero," Oz said. "But I keep naloxone in my house because I don't ever want to be that naive to think it can't happen. ... I'd rather be disappointed that my son made a bad decision than devastated for the rest of my life."

Terrigino is not sure whether stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic affected her daughter's decision to purchase illicit Percocet, whether it was an experimental phase, or something else.

“We’re pretty certain it wasn’t her first time experimenting with prescription medication, but it wasn’t an issue like we were dealing with an addict," Terrigino said.

"The issue is not if your child is suffering from substance abuse issues. It’s the likelihood that your child is going to buy some type of substance, whether it’s marijuana, a pill, cocaine, a vape cartridge, whatever it is, the likelihood that fentanyl is in it right now is so high that it really does only take one time.”

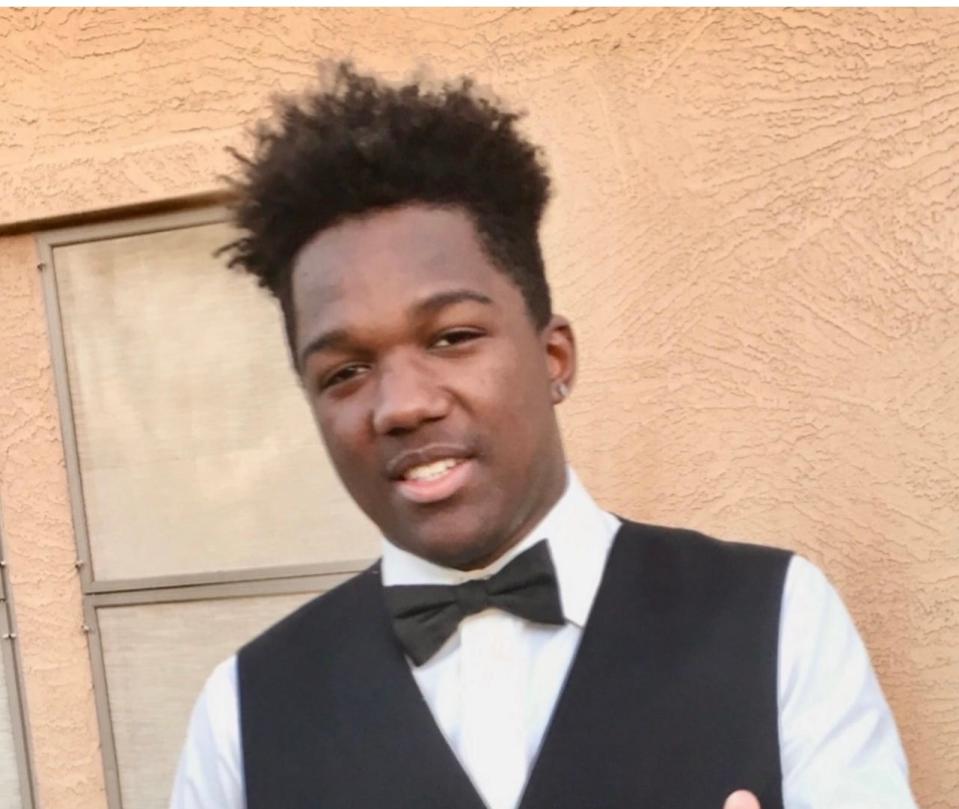

Maricopa resident Marissa Caballero knew about prescription fentanyl but hadn't heard about the illicit kind until the evening of Jan. 9, 2021, when her 15-year-old son, Issaiah Gonzales, was hospitalized after taking what he thought was a Percocet and passing out at a friend's house. He died the next day.

Mesa resident Wendy Plunk said she knew nothing about fentanyl until she saw her 17-year-old son's autopsy report. Zachariah Plunk died on Aug. 15, 2020.

San Tan Valley resident Eden Neville said her older brother Alexander was not aware of the dangers of fentanyl nor that he could die from just one pill. Eden is 14, the same age her brother was when he died on June 23, 2020, when the family was living in Orange County, California.

"Thanks to illicit fentanyl, the drug landscape of today is very different from what our parents experienced in their teenage years," Eden told attendees at the annual Arizona Drug Summit, held Sept. 7 in Phoenix and sponsored by, among others, the Governor's Office of Youth, Faith and Family. "Social media is a major outlet for a lot of youth. Social media is also where drug dealers advertise and sell. Because of that, drugs are so much more accessible. They are as easy to get as buying something on Amazon."

And while Arizona kids are getting sick and dying from fentanyl, many kids still don't know what it is. Nearly 50% of Arizona eighth-grade students who answered the 2022 Arizona Youth Survey said they'd never heard of fentanyl.

The survey, released Sept. 7, used responses from 51,448 students representing 22% of schools and 19% of all eighth-, ninth- and 12th-grade students in the state.

Just 17% of all the students surveyed said they had spoken with their parents about fentanyl in the past 12 months.

'Social media has made this even worse'

The age group of Arizonans who overdose on opioids most often is 25 to 34, according to state health officials. But over the past five years, children increasingly have been hurt by the drug.

The number of children who died from fentanyl in 2020 — 57 — is more than double the number from 2019, when 27 children died, Arizona Child Fatality Review data shows. In 2018, 12 died.

"It was a huge, huge increase," said Dr. Mary Ellen Rimza, a pediatrician who heads the state's Child Fatality Review Team. "Most of the deaths were teenagers. ... I think lots of young people aren't aware of the dangers. They don't know when they are acquiring something to try, a drug, that it could be contaminated with fentanyl — that is an especially major concern."

At the border: More than 15K 'candy'-looking fentanyl pills seized at port of entry

The program did not break out fentanyl deaths in kids before 2018. Rimsza's team looks at death certificates, law enforcement records and medical records to determine causes of death. The annual Child Fatality data released in November shows 44 kids ages 17 and younger died of fentanyl poisoning in 2021. The number is a decline from 2020 but still relatively high.

"Fentanyl is the most commonly identified drug we're seeing in the overdoses," said Sheila Sjolander, assistant director at the Arizona Department of Health Services. "Fentanyl has really swept across the country. It became more prominent in the Western states in the last couple of years. ... We understand that those counterfeit pills are just everywhere now."

State data shows increases in non-fatal opioid overdoses in kids ranging in ages from under 1 year old to 17 years old starting in 2018, when 131 such cases were reported. That was more than double the number from the prior year. In 2020, state data shows 335 kids experienced a non-fatal overdose from opioids. The number fell to 209 in 2021.

Terrigino believes her daughter purchased illicitly manufactured Percocet from someone she met on Snapchat, unaware that it contained fentanyl. Terrigino, who is a registered nurse, said she came to that conclusion after many conversations with her daughter's friends after Kaylie's death and from reading the journal her daughter left behind.

"Social media has made this even worse. ... These kids get on Snapchat, they place an order for whatever they want. They will bring them and drop them off at your house," Terrigino said. "Kids can pay through a cash app, all of these easy apps they have on their phone. Once it's been done, there's no following, no trace of the drug deal, essentially."

Fentanyl deaths among young Pinal County residents have prompted county officials to launch an awareness campaign. The campaign includes a video titled "Forever 17" that features Terrigino talking about Kaylie's death. Terrigino also appears in a three-part series created by the Pinal County Sheriff's Office titled, "Your Room Will Forever Be Silent" that focuses on fentanyl deaths in teens.

Kids' mental health suffered during the pandemic, research suggests

Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released in May 2022 says there were an estimated 107,622 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. during 2021, and most of those deaths were from synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl.

Beginning in 2020, adolescents in the U.S. experienced a greater relative increase in overdose mortality than the overall population, attributable in large part to fatalities involving fentanyl, according to a research letter published April 12 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

A growing prevalence of illegally manufactured fentanyl and its increased availability is certainly fueling fentanyl overdose deaths among kids, other issues are likely at play, too, among them mental health problems, which could lead kids to self-medicate with drugs, whether it's painkillers or something else.

While not every teen who overdoses on fentanyl has an underlying addiction, many of them do, said Dr. Scott Hadland, who is head of adolescent medicine at Mass General for Children, during a May 26 2022 web briefing about teens and substance misuse.

Illegal pot shop bust in Phoenix raises: How do you know if marijuana store is legit?

"They might just be trying opioids for the first time or may have only tried a handful of times," he said. "But many teens who overdose do have underlying addiction. And that’s important to note because I don’t know that that always gets the full attention it should."

Untreated mental health problems, most commonly depression, anxiety and history of trauma, are linked to addiction, Hadland said, as is a family history of addiction to any substance. Young people who struggle with mental health problems often go months or years without getting them treated, which contributes to addiction, he said.

Untreated mental health concerns, insufficient addiction treatment for youth and a dangerous drug supply remain ever-present, Hadland wrote in an Aug. 9 email. Also, there's an enormous, lingering mental health toll from COVID-19, he wrote.

"We are seeing unprecedented rates of mental health problems on the front lines of pediatrics, and that is likely to persist for years to come," he wrote.

Emerging research suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative effect on the mental health of many children and adolescents in the U.S. A national survey of 7,705 public and private U.S. high school students from 2021, recently published in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, found that during the 12 months before the survey, 44.2% experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, 19.9% seriously considered attempting suicide, and 9% had attempted suicide.

The Arizona Child Fatality Review report for child deaths in 2020 recommends increasing the availability of community training on how to use naloxone. Kids should know how to use it, too, particularly if they know their friends are using drugs, Rimsza said.

The same report recommends clinicians screen adolescents for substance use and mental health issues during regular visits.

Arizona decriminalized fentanyl test strips in 2021

The rise in fentanyl deaths among Arizonans of all ages led then-Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, in May 2021 to sign a law legalizing fentanyl test strips in the state.

The test strips, available for purchase online, and for free from several county health departments, were created to tell drug users whether there's fentanyl in the pill they are about to take. The original bill that led to the law was sponsored by state Sen. Christine Marsh, D-Phoenix, who lost her 25-year-old son, Landon Marsh, to a fentanyl overdose in June 2020.

While test strips can detect even traces of fentanyl, they don't detect specific dosages, Sjolander said.

"We know that some of the illicit pills have very high doses of fentanyl but you wouldn't know that from the fentanyl test strip. It will just tell you whether or not fentanyl is present in that particular pill," she said. "Hopefully, if they (the test strips) are used, it could certainly make a dent in the number of deaths we're seeing from fentanyl in particular."

The fentanyl test strips are a positive step, but they aren't going to solve the problem for kids, and may even miss detecting fentanyl in some pills, said Marissa Caballero, whose 15-year-old son. Issaiah Gonzales. died on Jan. 10, 2021, after taking a counterfeit Percocet pill that contained fentanyl, his family said.

Issaiah, a high school sophomore and the eldest of five children, liked Xbox and socializing and dreamed of playing in the National Football League. He passed out at a friend's house in the evening Jan. 9, 2021, after taking the pill. His mother said that while Issaiah's other friends took pills, too, her son was the only one who died. There have been no arrests, Caballero said.

Caballero says there's a "chocolate chip cookie" problem with the way fentanyl can be distributed in pills — just like chocolate chips are not found in every piece of cookie, fentanyl is not found in every part of every pill, she says. The fentanyl strips are "better than nothing" but are not a cure-all, said Caballero, who believes more education and awareness is what will make a bigger difference.

"With the test strips it's not 100%. You might test one piece of pill that has no fentanyl and the other piece does have fentanyl in it," she said.

Fentanyl test strips also may not detect all fentanyl analogs, which are similar to fentanyl but have a slightly different chemical structure, said Haley Coles, executive director of Sonoran Prevention Works, an Arizona non-profit that does outreach to people with opioid use disorder.

But the fentanyl test strip law was very specific and did not include the approval of more sensitive testing of drugs that's happening in other parts of the country. The advanced technology can identify forms of fentanyl that the test strips might miss, Coles said.

"Because of the way the law was written and they weren't comprehensive enough, those are all illegal (in Arizona)," Coles said of mass spectrometers. "We only legalized fentanyl test strips," she said.

East Valley football player struggled after hazing, family says

Zachariah Plunk, a high school football player who lived in Mesa, died in the early hours of Aug. 15, 2020, after purchasing what he believed to be a Percocet on Snapchat, said his mother, Wendy Plunk.

An autopsy report ruled Zach's death an accident and said his cause of death was from the "combined toxic effects" of fentanyl and the prescribed psychiatric medications he'd been taking under a doctor's supervision with no prior problems for several months. Fentanyl was the deadly factor, his mother said.

Zachariah, who went by Zach, was 17 when he died. The youngest of four children in his family, he had dreams of playing football at Baylor University and later having a career in forensics.

The family was able to see, via home security footage, that a dealer delivered the Percocet to the Plunk home at about 3 a.m. and Zach took a single pill while he was still outside. He collapsed and died. A teenage neighbor, out for a jog early that morning, first discovered Zach, his mother said.

"We woke up to an ambulance and the fire department out in front of our house," Wendy Plunk said. "We got dressed, went outside and looked and there was Zach."

Plunk said she believes her son was self-medicating due to trauma he experienced when he was a high school freshman, combined with the stress and isolation of going to school online during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Zach was a victim of hazing at Hamilton High School in Chandler, where he'd been a running back on the school football team, Plunk said.

Ever since the hazing, which involved allegations of sexual abuse, his mother said Zach had experienced mental health problems and transferred schools several times, which left him "heartbroken" because it interrupted his ability to play football, she said.

"He had been going to therapy for almost three years and he had PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)," Plunk said.

Zach was expecting to graduate from Desert Ridge High School in Mesa in December 2020, Plunk said, and he'd been planning to play on the school's football team in the fall. He'd gotten behind on some of his schoolwork when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March 2020 and school went online, which delayed his graduation, she said.

"When COVID hit, he was depressed and I think that's when he started dabbling a little bit with OxyContin and he was smoking a little weed," Plunk said. "We were trying to get him to stop. ... We didn't know anything about fentanyl. We didn't have a clue."

Plunk now tells kids, whenever she has the chance, to make sure they aren't alone if they are going to experiment with drugs. And she tells kids and parents to make sure they have a supply of naloxone whether or not anyone in their family is known to be experimenting or using illicit substances.

"Everybody needs to carry Narcan, because you never know," Plunk said.

Naloxone quickly reverses an overdose by blocking the effects of opioids and can restore normal breathing within two to three minutes, the CDC says.

More than one dose of naloxone may be required when stronger opioids like fentanyl are involved, according to the CDC, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse is supporting research into stronger formulations of naloxone for possible use in people who have overdosed on potent opioids such as fentanyl.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already approved two higher-dose naloxone products — Zimhi and Kloxxado — though critics have questioned whether more powerful doses are necessary, and whether they may cause severe opioid withdrawal symptoms.

"The development and marketing of more powerful opioid antagonists should be viewed with great skepticism," researchers from The University of Texas at Austin wrote in a paper published in the International Journal of Drug Policy in January.

"State health agency staff, public health professionals, policymakers, and clinicians should be aware that more potent, longer-acting opioid antagonists are not necessary and may have unintended consequences."

'I just had this sinking feeling. I knew something was wrong.'

Kaylie Tallant’s bedroom door was shut when her mother, Misty Terrigino, left the house for a nail appointment on the morning of Monday, April 12, 2021. That wasn’t too unusual, because Kaylie was attending school online. But by the time Terrigino returned about 11 a.m., her daughter wasn’t responding to text messages.

"I just had this sinking feeling. I knew something was wrong. ... Her door was locked, and my son had to help me unlock the door, and when I opened the door she was laying in her bed," Terrigino said.

"I ran in and I grabbed her, thinking maybe her AirPods were in and she couldn't hear me, and as soon as my son and I pulled her over, I could tell that she had been gone for awhile. I screamed to my son to call 911."

In Pinal County, where Kaylie lived, data from the Pinal County Medical Examiner's Office shows that fentanyl deaths among all age groups jumped to 72 in 2021 from four in 2017 — an eighteen-fold increase.

Kaylie was one of three Pinal County kids ages 17 and younger who died because of fentanyl in 2021, up from one in 2020, according to the Pinal County Medical Examiner's Office. No fentanyl deaths among kids 17 and younger were recorded by the Pinal County Medical Examiner prior to 2020. Pinal County, in central Arizona, has a population of about 460,000.

Pinal County's first-ever fentanyl death in a child happened on Aug. 18, 2020, county autopsy records show. About 9:30 a.m. that day, the brother of 15-year-old girl discovered his sister dead, sitting at the family's kitchen table in Eloy. The Pinal County Medical Examiner ruled the death an accident caused by acute fentanyl intoxication. The autopsy report said the girl had a reported history of drug use.

Some parents whose kids have died from fentanyl poisoning believe a lack of awareness is aggravating the problem.

Terrigino said she's met some families who feel shame about how their child died, but she says that sharing her daughter's story is a way of both honoring Kaylie's memory and hopefully helping other families avoid tragedy.

Showing improvement: White House sees signs of progress in opioid struggle as deaths continue

"I have been a firm believer that If we don't share this hard stuff, nobody will listen," she said. "If it helps one family not to live this life, then we are doing our children justice."

Terrigino is part of the Southeast Valley Community Alliance, which is comprised of parents in her area working to create more awareness about fentanyl dangers.

“Personally I feel like the education and awareness aspect is where we can have the greatest impact,” said alliance director Amy Neville, the mother of 14-year-old Alexander Neville, who died of fentanyl poisoning when the family was living in Orange County, Calif.

“We can pass more laws and hold drug dealers accountable, but there will always be more drug dealers. … The education and awareness piece is huge."

Neville established the Alexander Neville Foundation to raise national awareness about fentanyl and its danger to kids. She also does local community education as director of the Southeast Valley Community Alliance.

There have been no arrests to date in connection with the deaths of Kaylie, Issaiah, Zachariah and Alexander, their families say.

Families put pressure on Snapchat

Alexander Neville, a middle school student who loved Civil War and World War II history and dreamed of becoming a museum director, had attended a residential mood and anxiety program in February and March 2020. He had been doing better after going home, but his mother said she noticed a difference by June. Her son seemed “just not right,” she said. Among other things, he was having severe mood swings, she said.

Neville asked him if he was using drugs.

Initially, Alexander denied using drugs. But on June 21, 2020, he admitted to his parents that for the past week to 10 days he’d been experimenting with what he believed was oxycodone, purchased from a dealer he met on Snapchat.

The next morning — June 22, 2020 — Neville called the residential facility where he'd been previously treated to ask about getting additional help for her son.

Alexander never got the chance to get more treatment. Sometime during the early hours of June 23, he died from fentanyl poisoning. His mother went to his room to wake him up for an orthodontist appointment and found him in his bedroom, lying on a beanbag chair like he'd gone to sleep. The side of his face was blue.

“These dealers put their menus on Snapchat. Or they’ll say ‘I’m in the area, hit me up if you want something,’” Neville said. “There’s the whole Snap Map, which is a feature where they can be live and anyone can see where you are at.”

Families of kids affected by fentanyl, including the Alexander Neville Foundation, have been putting pressure on social media platforms to make it harder for drug traffickers to target kids. Early in 2022, officials with Santa Monica-based Snap Inc. announced they were taking more aggressive action to shut down dealers.

In a June 9, 2022, statement, Snap Inc. officials wrote an update to its actions against drug dealers, saying the company has "always had a zero-tolerance policy against using our platform in connection with illicit drug sales" and that it is combating the fentanyl problem with, among other things, improved technologies to detect drug trafficking activity and shutting down dealers who abuse the Snapchat platform.

Families say the company's actions haven't eliminated the problem with Snapchat. Groups such as the Organization for Social Media Safety also are working with members of Congress on drafting legislation to better monitor and track crimes committed on social media.

“There are a lot of different pushes out there, to make them accountable,” Neville said. “However, will it happen anytime soon? Probably not, because they have money and power. ... Snapchat will tell you they are doing all these things on the surface. But when it comes right down to it, it’s all smoke and mirrors.”

Katey McPherson, director of professional development at the online safety company Bark Technologies, is adamant that all parents monitor their kids' devices to ensure their online safety.

Kids' brains are not fully developed, and there are people online ready and willing to take advantage, she said.

The Chandler-based mother of four gives talks to parents and young kids about social media safety whenever she has the opportunity because so many adults have no idea about what kids are encountering via technology, she said, including sextortion and drug trafficking.

Thank you for subscribing. This premium content is made possible because of your continued support of local journalism.

"This is an adult issue. We have done a horrible job of just handing over these devices," McPherson said. "They (kids) are just crashing and burning all over the place and it's not their fault. We've literally handed the car keys over with no driver's ed."

Everything about kids' lives is on their laptop, their iPad or their phone; it's not a mystery, McPherson said. But too many parents of 14- to 17-year olds don't think about monitoring their child's devices, she said, and they should, because that's when life starts getting stressful. Some kids turn to substances to numb the stress.

Prevention needs to start when kids are still in elementary school, said McPherson, who is chair of the Social Media/Technology Impact Group of the Teen Mental Health House Ad Hoc Committee at the Arizona Legislature.

Then-state Rep. Joanne Osborne, R-Goodyear, chaired the committee, which began meeting in July 2022 with an aim to"research and review information regarding how substance abuse, bullying, and social media may affect mental health in Arizona’s youth, including teen suicide."

The committee included members of the state House of Representatives and the community and made recommendations to public and private agencies about ways to address teen mental health issues and improve access to mental health care.

"We as communities need to educate our parents and our kids at very young ages. The average age of experimentation is 11, which is sixth grade. And most parents don't think about talking to their kids until about ninth grade," McPherson said.

"We have a lot of work to do. It's daunting."

Reach the reporter at Stephanie.Innes@gannett.com or at 602-444-8369. Follow her on Twitter @stephanieinnes

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona kids are dying from counterfeit pills that contain fentanyl