Arizona prisons boast that laborers won’t end up back behind bars. That’s not true

Daniel Gorman should be better off.

While incarcerated, he worked at the largest privately held corporation in the United States — Cargill Inc.

He was paid $3.30 an hour, Gorman said, to operate a hydraulic-powered machine that compressed cattle feed into dense blocks that are sewn into bags and shipped to farmers and ranchers around the country.

But during a shift in November 2017, something went horribly wrong.

The block press machine’s sliding steel door got jammed. Gorman turned it off to diagnose the problem. As he checked for blockages — and in an instant — the steel door crashed down under sudden and immense hydraulic pressure, slicing his hand nearly in two, split between the middle and ring fingers, down to his wrist.

“All I felt was a firm pinch and then nothing,” he said. “I just seen it mangled.”

Gorman was hospitalized. Emergency surgeons sewed his hand back together, and as he recovered, he received a visit from a representative of Arizona Correctional Industries, the state-owned company whose chief product is the “captive workforce” within the Arizona prison system.

The message to Gorman was clear: “They basically blamed me (for the accident),” he said. “It was very unsettling. I felt like I was at fault and I wasn’t.”

Gorman returned to prison. But in the transfer from the hospital, the Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation & Reentry moved him to a different unit 100 miles away where he would have no friends or contact with other prisoners working at Cargill. After his injury, Cargill implemented safety features to the machine Gorman operated.

Corrections officers also confiscated all of Gorman’s personal belongings, including an old and overpriced television he purchased with savings from his job.

Gorman never worked for ACI again. He got out of prison in 2019, and, save for two weeks at the Arizona Department of Administration’s public surplus warehouse in Phoenix, he has been unemployed ever since.

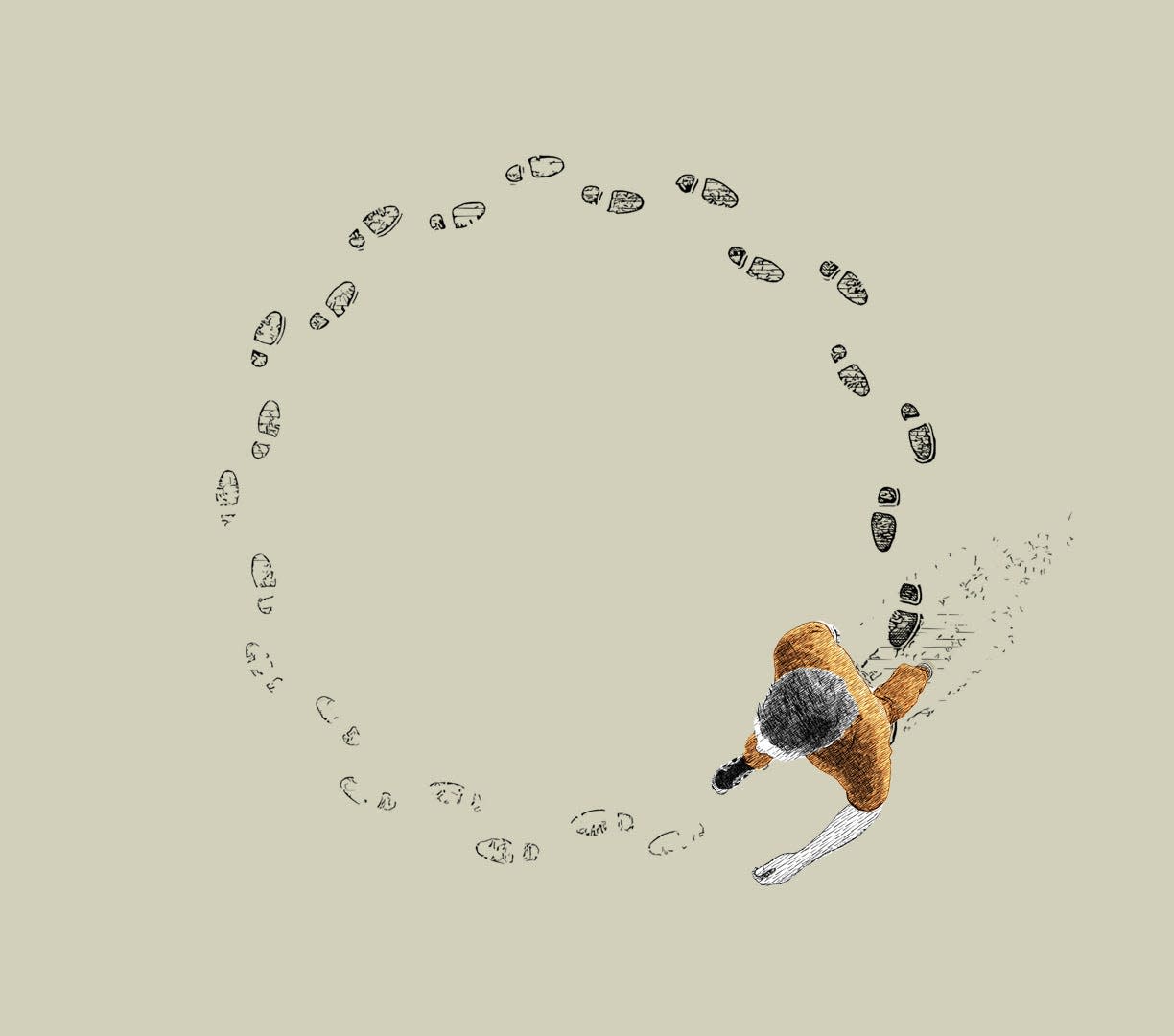

Now 39, he spends most nights unsure of where he will sleep, balancing the choices of finding a home for a night with the prospect he fears most — another stint in prison.

“It's very, very, very, very hard for me not to go back to my old ways right now, because I'm not working,” Gorman said, in reference to his long term drug addiction.

Arizona will spend $1.4 billion on its Corrections Department in 2023, primarily locking up people like Gorman who cycle in and out of prison.

Of the more than 30,000 behind bars, a precious few — about 2,000 people a year — work for Arizona Correctional Industries, or ACI.

Companies that partner with ACI benefit by being able to fill tedious and often dangerous jobs with a cheap and reliable workforce. They don’t pay workers' compensation, insurance and retirement program benefits, or payroll taxes.

In return, ACI and the Department of Corrections claim working for ACI is among the most effective tools available to help keep people from returning to prison.

In the case of Gorman, his job at Cargill was supposed to improve his odds of finding employment when he got out of prison, and stay out, saving the state from spending money on duplicative crime and punishment.

But Gorman and other former prisoners have described the work program as ineffective and exploitative. They said it doesn't provide job skills that would be applicable on the outside, and wages are way too low.

After collecting and analyzing reams of data without help from the Department of Corrections, The Arizona Republic and KJZZ Radio have found incarcerated workers leased to private businesses in Arizona are not much better off upon release than other prisoners.

Overall, prisoners who worked in ACI programs were slightly less likely to return than those who didn't, but outcomes varied, depending in part on how long each person was able to keep their ACI job. Workers who were able to remain employed in ACI roles for 10 months or more had the lowest recidivism rate — 24%.

But the vast majority of incarcerated workers assigned to private businesses worked fewer than 10 months. For them, the recidivism rate was 32% — nearly the same as other low-custody prisoners who did not participate in ACI and had been sentenced for nonviolent offenses — 35%, The Republic found.

Countless factors contribute to whether a person will return to prison, such as how much money workers were able to save prior to release, employment history before and after incarceration, educational attainment, substance abuse history, family history, residence, age, race, sex and much more. That makes measuring individual programs like ACI's especially challenging, said Kerry Richmond, department chair and associate professor of criminal justice at Lycoming College in Pennsylvania.

"There's really just not a lot of research on prison industries," Richmond said.

She is among a small contingent of experts on prison reentry whose research focuses on correctional industry programs like Arizona's. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on outcomes among women who worked in correctional industries in federal prisons. She has surveyed incarcerated laborers in Pennsylvania prisons and recently sought to launch a larger, multistate study "to see overall, what the effect of correctional industries programs were on reducing recidivism."

But Richmond and the other academics she was working with encountered similar problems The Republic faced while investigating ACI — a dearth of data from correctional industries and the departments that operate them.

"We came across just so many different barriers in terms of data collection," she said.

The Department of Corrections refused to provide The Republic and KJZZ with data they could use to evaluate ACI's work programs. It denied any information about inmate work history and even hand over a list of people among the incarcerated population who had worked for ACI.

So The Republic developed a computer program that automatically visited hundreds of thousands of public pages on the department’s website, extracting information on every person incarcerated since 1980.

What The Republic obtained excludes many important factors needed to fully investigate the impact of ACI work programs, and yet, the result was still the most comprehensive database of people inside Arizona prisons ever obtained by the public. The data also gives a unique look into how the Department of Corrections operates one of the largest and most profitable forced labor systems in the nation, with little independent oversight.

Questionable statistics

Throughout the history of the Arizona Department of Corrections, the majority of people who have been locked up have never been to prison before.

But in 2018, the share of people returning to prison surpassed newcomers. The trend has continued every year since, according to data collected by The Republic.

The cost of incarceration and the high rate at which people return to prison are two problems the Department of Corrections says it aims to solve by putting people to work for corporations.

"More than ever, Correctional Industries across the country remain critical to the successful reentry and reintegration of an offender back into society. ACI is our crucial resource for doing that,” Department of Corrections director David Shinn wrote in ACI’s 2020 annual report.

According to the Department of Corrections, prisoners who work for corporations through ACI or who make products at ACI’s manufacturing facilities are far less likely to return to prison than prisoners who have nothing to do with ACI.

But after conducting its analysis of data collected from the Department of Corrections website and from other sources, The Arizona Republic and KJZZ found the Department of Corrections has overstated the impact of ACI’s program to the public and lawmakers.

Among the general prison population, an average of 37% of prisoners released return within five years with an entirely new sentence. That compares with 30% of those who worked ACI jobs during their incarceration.

The difference of 7 percentage points may have little to do with ACI.

"While the point of (correctional industry) programs are to train and enhance the skills of those incarcerated, it is still a business and they often hire those individuals who have relevant prior work experience to minimize the need for training," Richmond told The Republic. "This may influence the impact of the program on recidivism, as someone with prior work experience may have had a lower likelihood of recidivism regardless."

The Republic measured recidivism by counting every person who returned to prison within five years after an earlier release — a time span widely used by criminology experts. The Republic’s measurements are conservative in that they only count people released from prison and who returned with a new prison sentence. They do not include people who returned for parole violations or for new arrests.

Neither the Department of Corrections nor ACI tracks whether people released from prison find employment, another important metric that Richmond said is needed to measure ACI's success. Claims regarding ACI’s impact on reducing recidivism instead rely on questionable statistical methods that are often impossible to verify.

“A recent analysis compared the reentry outcomes for inmates who worked in ACI programs with those who did not,” ADCRR Director David Shinn wrote in the company’s annual report for 2020. “The data suggests that ACI reduces recidivism compared to inmates who did not work ACI jobs by as much as 26.8% over a 3 year period.”

The Republic requested a copy of the analysis Shinn cited from ADCRR, but the agency insisted it did not exist. It is unclear where Shinn’s quoted “26.8%” originated or exactly how the agency calculated its rates, and the department would not say nor provide any evidence of how it came up with that number, so it cannot be directly compared to The Republic's analysis.

The newspaper found the recidivism rate was indeed lower among people who had worked for ACI prior to release, but not to the extent the agency claims.

On ACI’s website in February, the state-run company used similarly opaque statistics to showcase how work programs at ACI reduce recidivism. Its calculations, meant to be demonstrative of ACI’s success, didn’t add up. The proportional totals it calculated were mathematically impossible.

Those numbers disappeared from ACI’s website within days of The Republic questioning them. A spokesperson from the agency wrote in an email that the numbers were “taken down on the ACI website as some of the information was redundant.”

A spokesperson of the Department of Corrections also told The Republic the agency was "in the process of expanding its existing Research and Evaluation Unit to have greater resources to do a more comprehensive analysis."

‘Meticulous and fast’

Gorman spent the better part of a decade serving three different sentences — his first in 2006 and his last in 2017. He had charges that included vehicle theft and drug possession, all of them stemming from a meth addiction he struggled with for years.

His second sentence began in 2010. He stole a car — a nonviolent crime — and was placed in a medium-security yard, where he was eligible to work for ACI, which was marketed as a “desirable and highly sought-after job within the prison system … that inmates must earn and maintain,” according to ACI’s annual reports.

Gorman, who kept a low profile, hoped for an assignment.

“Just getting the job was a challenge. I was a good boy on purpose,” he said. “I wanted to make sure that I could get that job — it’s an escape.”

He was assigned to detail cars for Greater Auto Auction in Tolleson, a company ACI worked with for nearly three decades that sells its vehicles to companies such as Carvana and other used car dealerships.

Prisoners described fellow incarcerated individuals who worked at the auto auction, which is owned by the used car auction giant Manheim, as “zombies” and “beat up.”

One woman who used to work for the company said she would get cramps in her hands and would wake up not being able to open them fully after cleaning cup holders for eight to 10 hours a day, all week, for months on end. People incarcerated for drug problems said that they would often find narcotics in cars. Relapsing was a common occurrence for workers at the auto shop, they said.

In May 2015, ACI placed Gorman at Hickman’s Egg Farm, the state’s largest egg producer and another longtime employer of incarcerated people. He worked the “cage crew” in Tonopah and in Arlington, building chicken coops for thousands of factory farmed and free-range fowl. The work, he said, was “meticulous and fast” and “hot and smelly.”

Again, the job was promised as a way to get him the skills needed to be placed in a good job after prison so he wouldn’t fall back into his addiction or rely on criminal activities to make ends meet. Gorman worked at Hickman’s for 10 months before his release in 2016.

But Gorman didn’t land a job with Hickman’s after he got out. Instead, his position was filled by another prisoner.

Though ACI’s stated goal is to train prisoners in skills that will help them get jobs later on, the Department of Corrections does not see itself as a job placement agency, according to the department’s spokesperson, Bill Lamoreaux.

The Department of Economic Security, which runs the state’s Second Chance Center and provides technological skills to prisoners and directly places them with employers, said the jobs prisoners are forced into at the Department of Corrections don’t match with what employers want. “The (Second Chance Center) program differs from other ADCRR work programs as it provides participants with the employability skills that employers seek,” said Tasya C. Peterson, press secretary for the department.

It’s unclear what would have happened if Gorman had been placed in a job at Hickman's, or even if he had been taught an actual skill he could put on a resume and pair that with rehabilitation treatment inside.

Instead, within a year, Gorman was in prison again, for sentences related to drugs and theft. This time, ACI placed him with Cargill at its factory in Casa Grande.

‘It’s all about the money’

Gorman worked at Cargill in 2017 with 25 other incarcerated people.

One of them was Justin Wiessner, who, by any measure, was a star for ACI.

Wiessner spoke to The Republic despite fearing the Department of Corrections would retaliate against him by revoking his parole in response.

He clocked more hours than any other incarcerated worker at Cargill, according to data compiled by The Republic, holding virtually every role the factory would allow him to fill during his tenure.

“Pretty much any job there, I either did it or helped with it,” he said.

On the day Gorman was injured, Wiessner was clearing out a clogged vent elsewhere in the factory. He knew what had gone wrong because he had worked on the same machine.

Though Gorman had hit the off switch, he failed to disengage the hydraulic pressure, Wiessner said. That’s why the door came crashing down and sliced his hand.

In response to Gorman’s injury, Cargill implemented an automated safety system, Wiessner said.

“They made it so it was impossible for somebody to get in there without (the hydraulic pressure) being shut off,” Wiessner said.

Wiessner, who was incarcerated in 2014 and served multiple sentences for aggravated assault, explained he was arrested after an evening out with his girlfriend. He raised a gun to a group of about 15 people who he said were threatening her. He fired a round in the air to drive them away, then he and his girlfriend went home.

“No one was touched. No one was hurt. No property was damaged, no drugs were involved,” Wiessner said. “So in an ideal situation, I understand I could have handled it differently, the outcome would have been different and I wouldn't have done 10 years, but she could have been injured and I could have been injured.”

He pleaded to a 10-year sentence in prison, where Wiessner stayed away from people with a short fuse, cautious of his own.

“It's a bunch of dudes shoved in a sardine can, and there's people that get upset about just about anything,” he said.

His good behavior and a request to work an ACI job got him his first opportunity at Cargill.

The company brought on Wiessner part time at first, but quickly saw he was a top performer, setting records within the factory for productivity.

“It was just kind of, ‘Yeah, you're not going anywhere, we need you,’” he said.

Wiessner didn’t discover his work ethic in prison.

“I've always had a job, I've always been able to find jobs and keep jobs, because I was raised that you need to work,” he said.

But he said he saw plenty of people struggle in the factory alongside him before they would be fired or injured, like Gorman.

“A lot of people, they don't have that upbringing where they're told or taught to do that,” Wiessner said. “And that kind of ties in with the people that would not make it at ACI jobs.”

Corrections data pulled from the department's website shows more than half of the people ACI assigned to work at Cargill in 2017 lasted less than a month in their roles. Wiessner lasted three years, from 2017 until 2020. He likely would have worked there longer, if not for the pandemic, which shut down many ACI work programs, some permanently, like the one at Cargill.

Since his release on parole in February this year, Wiessner was able to quickly find a job hauling steel materials and fixing cars at a friend’s scrapyard in Sun Valley.

Asked whether he attributed his success in prison and outside to ACI or the job at Cargill, he replied: “No. I have always been this way my whole life, so me being who I am and what I do is not attributed to what ACI did for me or I did for them.”

For Wiessner, getting the ACI job and being the best at it was easy. But, he said, he would have had an easier time with his transition out of prison if he had just been paid fairly for his work.

If ACI cared about reducing recidivism, he said, it wouldn’t bilk workers of their wages — people would be less likely to return to prison. “If they were given the opportunity to have the money to cover themselves for rent or whatever until they do find a job, if they were able to.”

Three years working full time at the nation’s largest privately owned company netted him a savings of just $10,000 upon his release. He would have had more if not for being forced to rely on savings to pay for hygeine products while the pandemic raged. In the few months since he got out, he has wasted no time finding a place to stay, a phone plan and transportation, covering the most basic necessities to begin his life a second time. Now, nothing remains of his ACI earnings.

“That's actually some of the hardest-earned money I've ever done in my life, because of how little it is for the work you put out,” he said.

He believes if the Department of Corrections and ACI hadn’t docked so much of his pay, he may have walked out of prison with at least three times the amount he was allowed to keep.

“It's all about money with DOC. If they can scrape a buck or yank a buck from you, they're gonna do it,” he said.

Wiessner knows that he fared better than most people released from prison, including those who worked in ACI jobs. Without money, successful reintegration into society is often impossible.

“When you have individuals that don't have the ability to reintegrate into society as a civilian, as a human being,” Wiessner said. “There is a reason why there is recidivism.

“I understand there's people with lower mental capacity,” he added. “Well, those people are people, too, and they were incarcerated and they worked, and they're not able to reintegrate, so what's the first thing they know? They know how to sell drugs, they know how to rob somebody.”

‘I didn’t want to feel anymore’

Prison health and recidivism experts agree that work is important to being able to stay out of prison. But the jobs offered in programs like ACI’s are not helping.

“There is no evidence to suggest that prison labor or correctional industries are helping fix the incredible divides between who is able to get a good job and who is not,” said Wanda Bertram with the Prison Policy Institute, a national prison research group. While she said there is anecdotal progress of people who learn, for example, coding inside prison and then get higher base pay jobs, “there’s no way that the tech industry is going to furnish enough job opportunities or pathways to employ a significant number of people who are in prison.”

Instead, what many people argue needs to be done is a dual approach: give people job skills but also address the reasons why they’re in prison. For thousands of people inside, that means drug rehabilitation and therapy.

But the Department of Corrections has reduced its spending on drug addiction treatment and counseling for much of the past decade. In 2020, it spent $500,000 less than it did seven years earlier.

The programs aren’t just underwhelming to those seeking meaningful and effective treatment, they enroll just a tiny fraction of the incarcerated population that is in need of them.

In June 2022, about 84% of people admitted to prison were classified by the department as having “significant substance abuse histories.” But only 561 people were enrolled in the department’s addiction treatment program that month, fewer than the number of incarcerated people working in private businesses through ACI, according to Corrections data.

By contrast, more than 1,000 people were assigned to work for private companies through ACI programs in the same time period.

At prison intake, Department of Corrections staff evaluate the needs of people being admitted so staff can place them into treatment for mental health or addiction issues, among others. The department classified Gorman’s needs for both addiction and mental health treatment as “low” in 2010, despite a history of drug use and a prior drug-related prison sentence.

By his third prison term, the department had reclassified his need for addiction treatment as “high” and his need for mental health services as “moderate to high.”

During sentencing in 2017, he said he told the judge he didn’t want to return to prison — he wanted to go to drug rehab, but he said the judge told him he’d have to wait until he was released to seek it out himself.

“Why don’t you help me while I’m in, or help me before I go in, or help me so I don’t have to go in?” Gorman asked.

The best Gorman got was a contracted addiction treatment program through the Department of Corrections during his third and latest prison term. He described the program as being run in a classroom setting, taught by an instructor who referred mostly to material in a book. He described the program as ineffective.

“They just tell you what the book tells them to tell you,” Gorman said, adding the instructors would prompt groups with questions. “There’s no right or wrong questions, you just answer the questions.”

The programs Gorman said he’s gone to are nothing more than a throwback to '90s drug awareness training in middle schools — that drugs can cause harm and should be avoided — things people with an addiction already know.

“It doesn’t help anybody,” he said. “I did drugs because I didn’t want to feel anymore.”

But prison, he said, made him feel too much. He said one of the reasons he used drugs was to quell his propensity for anger. While incarcerated, he went to anger management treatment, where he said he was only given a book and told to read it and try and do as it said.

Gorman suspects he suffers from PTSD as a result of a difficult upbringing and traumatic life experiences. He said he witnessed regular violence while incarcerated, explaining he once had to step over a corpse and pretend he saw nothing in order to walk away from a dangerous situation. In life on the outside, his relationships with other people have been repeatedly painful, fueling a deeper need to numb any feelings.

He said he would seek therapy, if he only knew how.

“When it comes to the real world, I’m ignorant,” he said. ”I don’t know what to ask, how to ask, who to ask, and that sounds stupid."

Wiessner corroborated Gorman’s experience inside the prison’s betterment programs.

“You have people that are teaching these classes that haven't gone through half of the life experiences that people” in prison have, Wiessner said. “So you have somebody that has always had a job and never messed up, never had an addiction problem, was never in the wrong place at the wrong time and didn't foul up, and they're teaching these classes, skills for successful living and all this other stuff. They haven't been able to dig themselves out, because they've never had to, so half of their knowledge and half of what they say, they’re basically going off a book that somebody wrote that has nothing to do with any of what it takes to be successful after coming out of prison.”

Worse off than before

Even if Gorman wanted to work, he’s still partially disabled. The injury from Cargill — which he was not allowed to file workers' compensation for because prisoners don’t have the same labor rights as free people — has left his hand maimed.

He could have filed a civil suit — as almost a dozen other prisoners have in the past few years against various other ACI private employers — but the prospects of winning those are low, and court fees are high.

With no savings after laboring for the state’s most recognizable egg factory, the nation’s biggest used car auctioneer, and the largest privately held company in America, small obstacles seem insurmountable, he says.

When his driver's license and Social Security card were stolen while he was sleeping on the streets, he didn’t know where to go get new ones, or how to even pay for transportation to get there. The bad luck just fueled his desire to escape.

“It’s really hard to get sober when you’re homeless and people steal your s--- all the time,” he said. “Really hard.”

When the Department of Corrections was asked about prisoners’ claims of mistreatment and unsafe working conditions as well as the department’s lack of providing necessary rehabilitation, the department said in an email: “An inmate’s journey away from criminal conduct requires a commitment to personal growth and transformation. … ACI is an example of how serious we take that commitment.”

But if that were true, Gorman said, the work experience he had at Cargill and other ACI jobs would not have failed him in finding employment as he struggles to stay clean, battling an addiction that grips him “now, worse than before.”

The day he met with a Republic reporter to sit down for an interview at a Burger King in west Phoenix, Gorman said he had “made a point today to literally sit still,” because “I fight every day with choosing (whether) to do and not to do anything illegal.”

He was arrested in February on drug possession charges and was sentenced to probation on July 6. If he’s caught violating the terms of his probation, he’ll likely return to prison.

The period since his release in 2019 has been the longest he has remained outside of prison since his first admission in 2006. But he said his life on the outside is untenable, as what little freedom he has slips further out of reach, and he desperately hopes for an alternative to returning to prison.

But when asked what alternative he imagines most likely, he can only think of one:

“Probably dead,” he says.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona prison jobs aren’t helping inmates on the outside