Arizona senior care centers face little accountability when residents, staff are sexually assaulted

The 85-year-old woman collapsed on the bed after Manuel Corral finished with her.

When she felt like she could stand, she made her way to the bathroom to shower. It felt like he had assaulted her for hours, she later told police.

She knew he was still nearby, in the assisted living facility where she resided. She’d crept after him and seen him in a common room. Corral was a caregiver who worked the overnight shift at Heritage Village's building seven in Mesa.

She didn't tell her family until later. There was nothing they could do, she thought. Corral had already violated her.

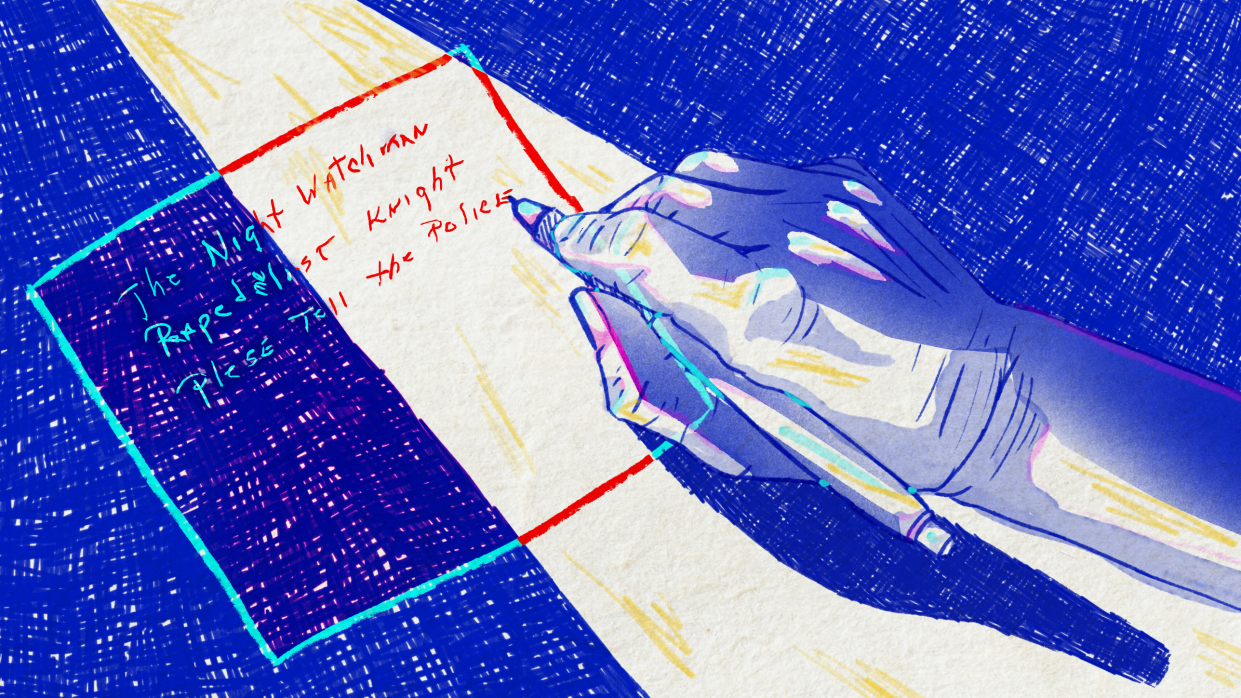

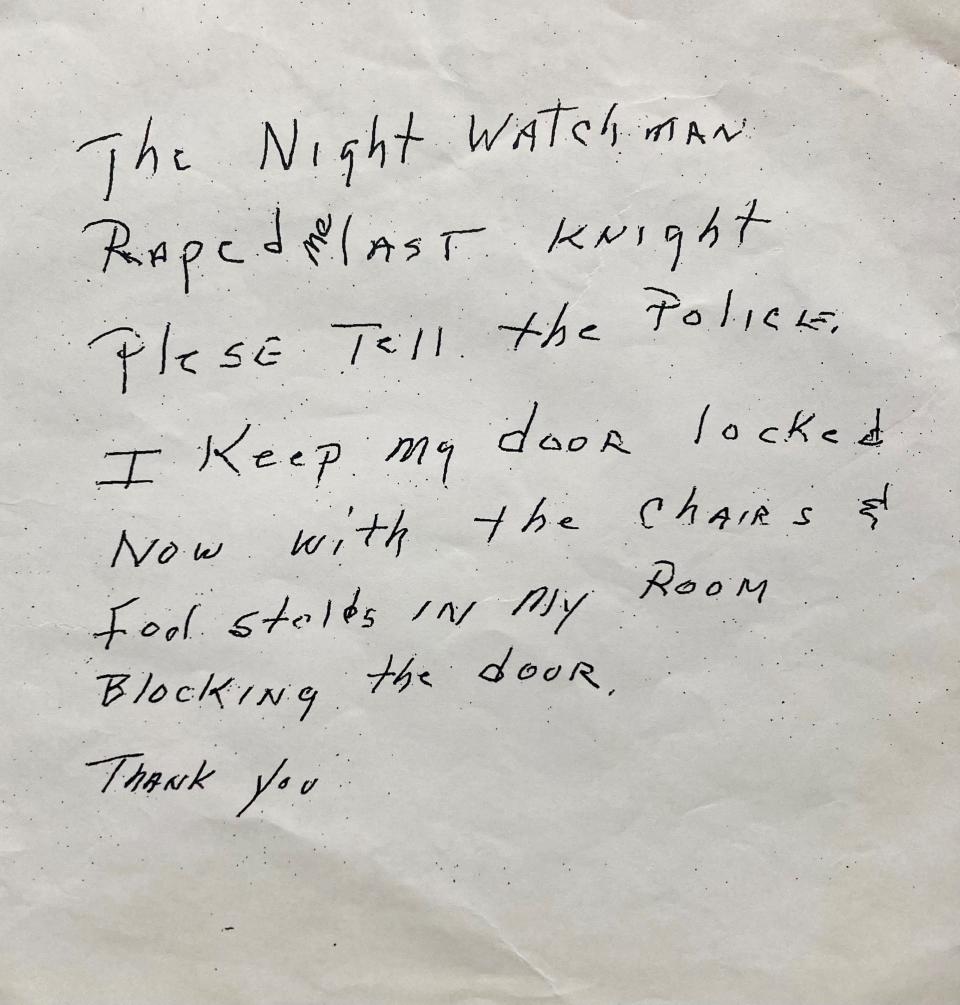

So she scrawled a note on a napkin explaining what had happened and slipped it under a locked door, into a room only accessible to facility staff. And she barricaded her door.

“The night watchman raped me last knight,” the note read. “Please tell the police.”

“I keep my door locked now with the chairs and foot stolls in my room blocking the door.”

“Thank you.”

She was sleeping when he came in, she later told police. She woke when he covered her mouth with his hand so she couldn’t “holler,” she said.

Corral was arrested and indicted on rape charges, but ultimately pleaded guilty to three counts of attempted sexual assault.

“It was an experience no woman ought to have,” the resident said during her forensic interview. “And I know they do. I’m not gonna be the only one it ever happened to.”

She isn’t.

Last year, The Arizona Republic requested three years’ worth of police reports from senior living facilities across Arizona, asking for calls stemming from assaults, domestic violence, fights, sex offenses and abuse.

The Republic built a database documenting those incidents, read hundreds of reports, analyzed citation and nursing home data, listened to forensic interviews and spoke to survivors, their family members, caregivers, regulators, police, facility managers and industry experts.

What emerged was a clear picture of fractured oversight among state agencies tasked with protecting vulnerable adults in care facilities.

One state department conducts facility inspections, another board takes disciplinary actions against managers and yet another entity investigates allegations of abuse. All rely on the other agencies to fill in the gaps where their authority ends. But none wielded that authority to its fullest to prevent further harm or to hold facilities and their managers accountable for the assaults documented by The Republic.

The system that informs the public and employers about caregivers and others who have abused vulnerable adults is months — sometimes years — behind.

Facilities sometimes hinder police investigation or forgo looking into allegations in accordance with the rules, quietly kicking out accused residents or firing accused employees.

People living in nursing homes and assisted living facilities — some of Arizona’s most vulnerable residents — bear the brunt. Workers at these centers have ended up in harm's way, too.

There’s limited data tracking reports of sexual assault at nursing homes and assisted living facilities, and no guarantee that every assault is reported. Nationally, sexual assault is one of the most underreported crimes. More than two out of every three sexual assaults go unreported to police, and among the elderly, that rate is even lower: Only 28% of elderly survivors report to police, according to statistics from the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.

In Arizona, Adult Protective Services — a program nestled within the state’s Department of Economic Security — is responsible for receiving and investigating allegations of vulnerable adult sexual abuse and assault at care facilities.

When allegations are substantiated, the state puts perpetrators on its public-facing registry, where their names remain for 25 years.

But Protective Services rarely substantiates anything. Its own staff members have cited concern about the quality of their investigations.

When The Republic pressed program spokespeople for a clear answer on the number of sexual assault substantiations Protective Services has made over the past couple of years, they provided three different figures within a three-day period.

The program’s own dashboard does not accurately reflect the figures provided to a reporter.

Between October of 2021 — when the program first put sexual abuse and sexual assault reports in their own category on its public dashboard — and this October, the agency opened investigations into more than 1,600 allegations of sexual abuse and assault.

During the same period, it substantiated less than 1% of that number.

Facility didn't provide details of assault to police, family

Larry met the woman who would become his wife when he was 25. She was petite — though she always wore shoes with little lifts, to make her seem taller — had short brown hair, a talent for cooking and a laugh that still makes Larry smile.

“She was my whole life, really,” he said.

When his wife started showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease — asking the same questions over and over, growing restless at night — Larry devoted himself to ensuring she was cared for, first at their home and later at Scottsdale’s Amber Creek Inn Memory Care, where she moved in early 2020.

He visited her daily, and when the COVID-19 pandemic barred him from the facility he stood outside, masked, talking to her through a window screen.

Larry moved her to Scottsdale's Lone Mountain Memory Care in April 2021 after a few nasty falls at Amber Creek, one of which broke a bone in her pelvis.

By the time she moved to Lone Mountain, his wife’s speech had trickled to mumbles and hums of agreement or dissent, with the occasional firm “No!” that told Larry she was upset.

Her bone had mended, but her mobility hadn’t come back. She used a wheelchair and needed help with daily rituals like bathing, toileting and eating.

She was still in there, though, the woman he knew. He saw it in the eyes that still flared with recognition when they beheld him; in the arms that still reached for him, decades after their wedding day.

“That tenth of a second, you would think ‘she’s back,’ he said. “And then she would fade.”

At first, things at Lone Mountain seemed OK, Larry said.

But then the former police detective started to notice slip-ups that made him suspicious: A cigarette butt on the floor of his wife’s private room. She didn’t smoke. Her carelessly cluttered bathroom counter. He was paying for her to be treated the way he’d treat her. The sloppiness upset him, he said.

His daily visits to the facility left him uneasy about the state of its staffing — the constant turnover, the lack of staff where it seemed like staff should be. It all began to grate.

Larry did everything he could to make sure his wife was comfortable: he bought her seat pads, her disposable undergarments, her bed. At the facility director’s suggestion, he even bought his wife a dark red recliner so she could rest comfortably in the facility's living room.

She was sitting in that recliner when a male resident with dementia came up beside her, put his hand under the blanket in her lap and touched her inappropriately.

By the time a staff member walked in and saw them, it was too late. The employee told police he’d left the room for a few minutes to get drinks — no other staff were in the room watching — and when he returned, the male resident had a "sexualized" look on his face while his hand moved in the woman's lap.

The employee found the whole scene "disturbing," he told Scottsdale police detective Evelyn Ivanoff, because she was just “helpless and laying there.”

Larry felt anger rise in his throat when Kyla Parker, then Lone Mountain’s manager, called about the incident. She kept the details vague: Larry’s wife was fondled by a male resident, Parker told him.

He jumped into his car and tore off to the facility, his mind racing: Why did this happen? Where was the caregiver who should’ve been watching her? The one who should have prevented this?

He pulled up to Lone Mountain, slid out of his seat and charged through the facility's doors. His beloved was the first person he saw.

Parker was the second. He asked for details about the resident who had assaulted his wife. She wouldn’t provide them.

He insisted that the man who had touched his wife — whomever he may be — leave the facility. Immediately. Parker said they’d have him out within 24 hours.

They did.

But Lone Mountain used that action to justify why they weren’t providing the detective information, Ivanoff said in an interview with The Republic. The man, the facility told her, was no longer a resident, no longer their responsibility; they didn’t know where he went. The detective would need a warrant to obtain any documents she sought, they said.

It took a few hours and a call to the facility manager's supervisor to get the man’s name when the detective asked for it.

A month after the incident, Parker told the detective she would share a copy of the facility's internal investigation paperwork with her after she brought them a warrant.

But the detective never received that paperwork. An employee later told an Arizona Department of Health Services surveyor that they were “unable to locate” any documentation of an incident investigation.

Ultimately, it took the detective six months and the search warrant to locate and speak to the man who groped Larry’s wife.

More than a year later, Larry is still finding out what really happened that day.

Even without knowing the details, though, he knew he wanted the state to hold Lone Mountain accountable for his wife’s assault.

At his behest, the police detective called the Health Department to tell them about her investigation at Lone Mountain. The department looked into it and cited the facility last November for failing to document its investigation into the incident and report it to Adult Protective Services or the police, the way facility employees are supposed to under Arizona law. Larry had to call the police.

That citation marked the end of it. The Health Department levied no fine. Lone Mountain came out of the investigation with a requirement to submit a plan of correction to the state.

In that plan, Lone Mountain management stated that the facility's executive director would review incident reports during morning meetings to ensure any suspected abuse was investigated and the "suspected of abuse policy" was followed.

"It was unacceptable," Larry said. "They got off with a slap on the wrist.”

The facility directed The Republic to Spectrum Retirement Communities — the company that operates Lone Mountain and seven other Arizona facilities, according to its website — for comment. Spectrum did not respond to multiple emails from a reporter.

Keith Stock, who worked for Lone Mountain as a caregiver and medication technician between August 2022 and June of this year, said he felt like Lone Mountain's management fostered a culture of silence.

“They are trying to protect themselves at all costs,” Stock said, “Regardless of what’s going on with the people that are under the roof.”

Lone Mountain was understaffed during his time there, Stock said, and management and caregivers alike saw near-constant turnover.

“The ratio in the daytime would be one care staff to every 17 residents. And I tell you, on average, I would work 70-plus hours in one week. They were that short-staffed,” he said.

Arizona has no minimum staff-to-resident ratio for assisted living facilities, but some other states do. Nevada requires one staff member for every six residents during waking hours in residential facilities licensed to care for people with Alzheimer's disease or related dementia.

Adequately staffing facilities with well-trained employees — and a qualified, experienced manager who can ensure policies upholding a professional standard of care are implemented — is a critical part of preventing resident-on-resident sexual assault, said Eilon Caspi, a researcher at the University of Connecticut with a doctorate in gerontology.

Having social workers on staff is especially crucial, Caspi said, because they can consistently evaluate whether a resident with a progressive cognitive disease — like Alzheimer’s or dementia — is capable of consenting to sexual contact.

In Arizona, there’s no requirement for assisted living facilities to have a social worker on staff. Facilities aren’t required to have nurses or nursing assistants on staff, either.

“Not having a social worker in an assisted living residence is a recipe for neglect and extensive violations of residents’ rights,” Caspi wrote in an email. “States not having laws requiring having nurse aides and nurses on staff in sufficient numbers — at all times — in assisted living residences caring for a vulnerable and frail population is a crime.”

When The Republic asked Jennifer Awinda, who has managed several Arizona assisted living facilities, how assisted living centers could prevent resident-on-resident sexual assault, she said she didn’t know what she could do other than tell residents to lock their doors.

“If we had more people with more eyes on (residents), then yes, we could prevent a lot of this stuff,” Awinda said. “But if you’ve got two people — or even just one person a lot of times — working in a dementia unit, and you’ve got 20 people or 30 people, that one or two people is not going to be able to do much.”

‘I know they don’t care’

Arizona’s piecemeal regulatory system can allow facilities and their managers to avoid consequences when residents are sexually assaulted — even when they created the conditions for that assault to occur.

Gaps are especially glaring at assisted living facilities. Three state entities are supposed to keep an eye on them, license their managers, enforce rules governing their operations and handle complaints that crop up: the Department of Health Services, Adult Protective Services, and the board that licenses facility managers (the Board of Nursing Care Institution Administrators and Assisted Living Facility Managers). All rely on sharing information to fulfill their roles, but are separate from one another.

The Health Department has the authority to cite assisted living facilities if their managers fail to ensure a resident is "not subjected to" abuse. But the agency relies upon Adult Protective Services and law enforcement to decide whether abuse occurred, a department official said.

Adult Protective Services investigates individual incidents of abuse within facilities, but its jurisdiction doesn't extend to looking at whether a facility broke the rules that govern them in relation to those incidents.

Most of the time, the Health Department must cite and penalize a facility before the board that licenses their managers learns of issues and opens a complaint investigation.

The multi-entity system worked in Arizona before — but it has stopped functioning, due in part to staffing trouble and failures in agency leadership, former Health Department director Will Humble said.

"What we have in this system is three points of failure," Humble said. "And because all three have failed, this whole system has failed."

The problem has gained some attention: Officials who review regulations in Arizona have questioned the oversight system’s effectiveness.

“I find that from all of the boards that we’ve talked to so far, that everybody’s pointing to somebody else. Nobody wants to accept responsibility for the gaps that I see in what’s going on,” Frank Thorwald, a member of the governor’s regulatory review board, said during an October meeting. “If these rules are so effective and so concise, and everybody is working together, why are we having problems?”

Though assisted living facilities are licensed and inspected by the Health Department, they don't have to report allegations of abuse, neglect or exploitation to the agency, unlike nursing homes.

Instead, state law and Arizona administrative code require assisted living employees to call Adult Protective Services or law enforcement about sexual assault and other forms of abuse or neglect.

On the face of it, the fragmentation “seems as though it limits rather than increases the state’s ability to effectively oversee residents’ care” in the assisted living sector, Caspi wrote in an email.

Arizona law charges the Health Department with surveying assisted living facilities annually, with one big caveat: If a facility has no violations in one year, investigators can’t return for another survey until two years have passed, unless a complaint triggers an investigation. In the meantime, the state only requires facilities to keep documentation of assault allegations — and internal inquiries into them — on file for a year.

But even that doesn’t always happen.

Facilities licensed to serve residents who need the most help were cited at least 19 times over the past three years for failing to document, investigate or maintain documentation for any allegations of abuse, neglect or exploitation, according to citation data collected and analyzed by The Republic.

“Providers are acutely aware that if they document adequately, this might be used against them in court or even by state survey agencies with citations and sanctions, etc.,” Caspi said. “So there’s a lack of incentive to document.”

Many facilities that Ivanoff, the Scottsdale police detective, has responded to recently couldn’t provide her any documentation of internal inquiries about the incidents she was investigating. Instead, they told her the process was conducted verbally, she said.

Ultimately, unless an employee or family member files a complaint with the department to trigger an investigation, there’s a good chance the Health Department won’t find out about incidents at assisted living facilities, Awinda said.

More frequent surveys make the department a more efficient regulatory body and benefit facility residents and employees alike, a department official said, and they have worked to focus resources on conducting inspections on time and investigating complaints.

But during her 17 years working in the senior living industry, Awinda has seen state surveyors fail to cite facilities for all manner of infractions, from bedbug infestations to incidents of abuse and neglect, she said.

She recently submitted her 30-day notice of resignation to her supervisors at Beehive Homes of Gilbert, the facility she managed for the last year and a half or so. Disillusioned with the senior living industry and the regulators who oversee it, she’s not planning on managing a facility again, she said.

“I don’t know how bad the staffing is at DHS, but I know they don’t care,” Awinda said.

'I don't ever want to go back to a nursing home again'

Management at some facilities has allowed staff and residents previously accused of sexual assault to continue having access to other residents, endangering the people entrusted to their care.

Employees are sometimes victimized, too — like the nurse who was working at Mesa’s Desert Blossom Health & Rehabilitation when a resident assaulted her.

The job was tough from the day she started in June 2021. The nursing home was constantly understaffed and supplies were always running low, she said. The Arizona Republic does not generally name victims of sexual assault.

Desert Blossom fell short of recommended minimum registered nurse and certified nursing aide staffing standards in 2021, a Republic analysis of day-by-day nursing home staffing data found.

“I'd literally be sick in the morning before I go to work,” the nurse said. “Because I didn’t know if I had any CNAs that day, I didn’t know what I was walking into every morning.”

Two years ago, on Christmas Eve, she walked into Bernard Barton’s room. She went in alone: She saw no green “cares-in-pairs” sticker on Barton’s nameplate, she said. Those stickers let employees know if they need to enter in pairs because a resident could hurt them, or has a history of accusing staff members of assault, the nurse said.

But she saw no sticker, even though Desert Blossom management knew Barton’s history. It was the first thing his family told the nursing home when they were looking for a placement, his daughter said: Barton had attacked someone before.

He was on supervised release, according to a police report. A few months earlier, he'd been convicted of sexually assaulting a nurse who came to his home for a welfare check in 2019.

He’d seized that nurse by the back of her head and kissed her, forcing his tongue into her mouth. He forced her to her knees and trapped her while she packed her medical equipment, groping her chest. He put his hands under her pants and inside her body.

She struggled with him, trying to keep her pants’ elastic band around her waist. She asked him to stop.

The nurse at Desert Blossom went to care for him with no knowledge of his history.

She had leaned in to tell him something when he seized the back of her head and pulled her toward him, holding her down. He forced a kiss, groping her chest as she screamed and tried to push out of his grip.

She doesn’t know how she disentangled herself, how she got out of the room. She just remembers sprinting to find the first staff member she could.

She wanted to go home, but couldn't. The facility was too short-staffed. She worked the rest of the day in a daze, her mind whirling.

The facility administrator seemed concerned for her, she said. He called law enforcement.

When the police arrived, the nurse told them she wanted to press charges.

Their response?

“The cop was kind of just like, ‘Well, you know he’s old, he’s in a nursing home, nothing ever really gets done about it,’” the nurse told The Republic. “There’s really no point in pressing charges because nothing’s gonna happen, basically, is what he told me.”

She felt like there was nothing she could do. She went part-time at Desert Blossom the month of her assault, shaving down her working hours until she was only there one day a month.

Barton was promptly removed from the facility, the nurse said. But for her, it was too little, too late.

She works at an all-women’s clinic now, after a stint in a dental office where she pondered whether she wanted to be a nurse any longer. She doesn’t want to work with male patients.

“For a long time, I didn’t even want to be intimate with my partner or him touch me because I just kept feeling that guy every time it would happen,” she said, a tremor in her voice. “I don’t ever want to go back to a nursing home again.”

Desert Blossom refused to provide The Republic with contact information for the manager when a reporter called. Management did not respond to multiple emails from The Republic.

When The Republic reached out to Barry Port, chief executive of the Ensign Group — the holding company that indirectly owns Desert Blossom — he told a reporter that the facility is operated by its own employees and leadership. That leadership is the best source of information about what's happening at the nursing home, he said.

"It is clear to me that neither you nor The Arizona Republic (at least over the past several years) have an open or friendly view of the skilled nursing industry," Port wrote in an email. "In light of that, it is possible that the facility leadership may not be interested in engaging with the media."

The state Health Department has no record of someone reporting the nurse’s assault, a department spokesperson wrote in an email, and the agency doesn’t have the jurisdiction to investigate resident-on-staff assaults.

The rules governing nursing home and assisted living facility operations focus on resident care, resident rights and resident protection.

But the Health Department — the entity in charge of enforcing those rules — doesn’t always levy consequences for breaking them.

Police took a call from Immanuel Campus of Care in Peoria in February 2022 when a resident there said she was sexually assaulted by a male resident after a smoke break.

The nursing home’s then-director of clinical services, Susan McCarthy-Robinson — now its administrator — told police the man had a history of being “handsy” but was “always honest about it when he is questioned.”

The woman didn’t remember some details of her alleged assault or which staff member she’d told afterward, McCarthy-Robinson told an officer, and the man denied doing anything to her.

Both residents lived in the facility’s "mental health ward," the officer wrote. Police closed the case; the incident report doesn’t document conversations with either resident, or a police officer going onsite.

Three months later, police were called to the facility again: The same male resident was accused of sexually assaulting another woman.

This time, the report documents a witness, signed and dated statements and a police officer on scene. The woman was distraught, the officer noted.

“I felt uncomfortable to the point I didn’t feel like a woman,” she wrote in her statement.

Staff told police they’d separated the man from the woman, placing him in another unit at the facility after she told them she was assaulted. Police submitted a charge of sexual abuse against the man to the county prosecutor.

The county moved forward with the case, taking the resident to court, but ultimately asked a judge to dismiss the charge against him. The judge did.

In a statement emailed to the Republic, McCarthy-Robinson noted that staff members weren't involved in any resident-on-resident sexual assault allegations. A facility executive followed up with The Republic and asked a reporter to "quit reaching out" to the facility and its administrator.

Nursing homes are required to report alleged sexual assault to the state Health Department, and Immanuel Campus of Care complied with that requirement, self-reporting both allegations to the agency. But the department didn’t cite the nursing home or conduct an on-site investigation for either report, instead reviewing them and closing them out, a department spokesperson said in an email.

“Due to the nature of the crime that was committed, it was determined that the incident would be handled by law enforcement as a criminal event,” spokesperson Siman Qaasim wrote. “However, we have made substantial changes to our investigation processes since these incidents occurred last year.”

“We would likely initiate an onsite investigation if a similar complaint or self report was submitted today,” Qaasim wrote.

A May 2023 report from the Arizona auditor general — the latest in a string of reports detailing problems with the Health Department's nursing home complaint investigation process — said the department had stopped closing self-reports without going onsite. But it pointed out that the department put off investigating some abuse, neglect and sexual assault allegations for months when they should have acted much sooner.

The continued problems “may put long-term care facility residents’ health, safety, and welfare at risk,” the report stated.

Caregiver accused of physical and sexual assault eludes system

One of the incidents that most illustrates the senior care regulatory system’s shortcomings happened at the troubled Heritage Village assisted living center in Mesa.

It likely was preventable: State agencies, police and facilities all failed to stop a man accused of physically and sexually abusing vulnerable adults from working at facility after facility.

On Valentine’s Day night in 2020 — a Friday, not long before the COVID-19 pandemic was announced — the nighttime caregiver, Corral, woke the sleeping resident by putting his hand over her mouth. He touched her breasts and genitals before rolling her over and vaginally and anally raping her, she told a forensic interviewer.

He forced his penis in her mouth, she told the interviewer. She felt like she couldn’t breathe. She mostly kept her eyes closed while she was assaulted.

Corral’s attack left the woman with vaginal and anal contusions, abrasions and redness, swelling and tenderness. It left her feeling unsafe in a place that was supposed to protect her. It left her scratching herself from anxiety, putting new wounds on her cheeks.

She piled all the furniture she could move in front of her bedroom door and wrote that note — the one scrawled on a napkin, telling staff what had happened to her. She later told her son nobody would see it until the following Monday.

This wasn’t the first time a resident had accused Corral of misconduct. Not the first time at Heritage Village, not the first time in general. But it was the first time allegations against him resulted in consequences that would bar him from care facilities.

Eight years earlier, in February 2012, Corral was a caregiver at Heritage Lane Behavioral Assisted Living in Mesa. There, a resident said he’d sexually assaulted her over two nights while she was in bed, forcing her to perform oral sex on him. At first, the resident told police she didn’t want to press charges because it had happened before and nobody had cared.

Even when she changed her mind, it still seemed like nobody did: Corral denied the accusation during his police interview, a swab of the resident’s mouth revealed no sperm, and the investigation was inactivated.

He admitted to putting his penis in the resident’s mouth when police investigated him for the incident at Heritage Village.

Corral was suspended from Heritage Lane and later terminated, according to a statement provided by Reed Gunnell, Heritage Lane’s executive director.

Adult Protective Services was “absolutely” notified about the assault allegations at Heritage Lane, Gunnell said. But Corral wasn’t added to the agency’s registry of abusers then, and officials would not confirm or deny an investigation into him.

By the time police interviewed him, he was working as a caregiver at a different facility.

Arizona law requires facility owners to make “documented, good-faith” efforts to contact a potential caregiver’s previous employers to help determine if they’re fit for a position in a residential care facility or nursing home.

The state Health Department enforces this law, a spokesperson said. It has cited facilities licensed to serve residents who need the most help for failing to call a staff member’s previous employers five times over the past three years, a Republic analysis found.

To his knowledge, Gunnell said, no employers ever contacted Heritage Lane about Corral’s work there.

And so Corral remained a caregiver in the system, moving from facility to facility.

Roughly two years after Corral’s suspension at Heritage Lane, Mesa police responded to two calls about Copper Village Assisted Living, now Whitestone Senior Living after a change in ownership this summer. Corral was accused of physically abusing two male residents.

Caregivers said they put one of them to bed with no injuries. When the morning shift arrived, the man had a dislocated shoulder, abrasions, bruising that matched the size and shape of the water cups provided to residents, and marks on his throat that suggested someone had grabbed it.

One of Corral’s colleagues told police Corral was “aggressive with everyone.” Another said he was always annoyed with residents if they were up at night.

Corral, the only caregiver on duty that night, implied the man had fallen.

The second resident said Corral had swore at him and smothered his face with a pillow. He told police Corral went into the bedroom of the woman who lived across the hall from him and shut the door.

Copper Village told Corral not to come to work pending the investigation into the first resident’s injuries, and the second resident’s partner called Adult Protective Services to report his allegations, the police reports state. But Corral’s name still didn’t appear on the agency’s registry, and there’s no way for facility hiring managers to find out whether the program is investigating someone.

So when police interviewed Corral about the incidents a month after the second Copper Village call, he’d — once again — moved jobs. He was working at Arbor Rose Senior Care. The assisted living facility hadn’t asked him why he was no longer working at Copper Village, he told Mesa police, and he hadn’t volunteered the information. He said he didn’t report any suspensions or firings on the application for his new job.

By the time Heritage Village hired Corral, he’d been fired from at least one assisted living facility and suspended from another. Three police reports detailed allegations of physical and sexual assault against him, and he was reported to Adult Protective Services at least twice.

Heritage Village issued a statement in 2020, after the assault, saying, "We are deeply saddened regarding the incident of assault at our community. We are working in full cooperation with law enforcement and all governing agencies, and making every effort to restore comfort and peace of mind to our residents, families and staff." When Corral was hired, all necessary background checks were done and found clean, the statement said.

Neither Courtney Thomas, who managed Heritage Village when Corral assaulted the resident, nor Wendy Mauch-Kenyon — the manager before Thomas — took responsibility for his hiring. Both women said the other hired Corral.

SAL management group — the company that operated Heritage Village at the time — has not responded to The Republic’s request for comment.

Four months after the assault, the board that licenses and disciplines facility managers voted not to open an investigation into Heritage Village’s manager. Neither Thomas nor Mauch-Kenyon faced disciplinary action in connection with the incident.

A Heritage Village employee told an officer that Corral had no other problems on file at the facility. But a complaint submitted to the state Health Department reveals residents had raised concern about Corral’s behavior before: About a month before the assault, Corral was accused of inappropriately touching a resident’s private parts while changing their briefs.

And several months before that, a resident told a caregiver that they were inappropriately touched by Corral. The caregiver marked the allegation as a hallucination and filed it into the resident’s chart instead of reporting it up to facility administrators, according to a citation.

Arizona far below national average on confirming problems

Adult Protective Services’ website states that the purpose of its registry is to prevent the victimization of vulnerable adults by someone who’s done it before.

But Corral didn’t appear on that registry until nearly a year after his arrest on sexual assault charges in 2020. Emiliano Fausto and Akram Kareem Al Naayli — two of the people added to the registry for sexual abuse or assault this year as of September — perpetrated the incidents that led to their addition five months before showing up on the list and more than a year before showing up on the list, respectively.

More than half the people on the registry were added by the agency a year or more after they abused, neglected or exploited a vulnerable adult, a Republic analysis found.

Substantiating claims is a lengthy process involving layers of bureaucracy that extend outside of Adult Protective Services: When the program proposes an allegation for substantiation, it is reviewed by the Attorney General’s Office. Alleged perpetrators are offered the opportunity for a hearing, handled by the Office of Administrative Hearing. If they choose to move forward with an appeal, then — when the hearing is over — the Department of Economic Security director makes the final decision on whether to place the person's name on the registry.

Adult Protective Services has placed 11 people on the registry under the sexual abuse and assault category over the past two years. Five of those people were added in roughly the past month — after months of questions from The Republic and a state audit criticizing the program for its low substantiation rate.

When a reporter asked why the program's registry doesn't match the data initially provided, a spokesperson said some substantiated allegations "should have been retroactively adjusted" to be categorized as sexual assault. A few substantiations under the program's "abuse" category can be categorized as sexual assault, the spokesperson said.

The program has additionally verified 46 sexual assault allegations since October 2021, according to department spokesperson Tasya Peterson. Protective Services "verifies" allegations of sexual abuse when the evidence points to an assault having occurred, but the agency is unable to identify who did it or if the person accused is a vulnerable adult themselves.

The number of sexual abuse and assault allegations substantiated compared with those investigated reflects the many steps in the investigation process, Peterson wrote. Vulnerable adults might be unable to assist in investigations “due to the nature of their physical or cognitive impairment," she wrote.

There’s a “high burden of proof” to substantiate allegations, she wrote, because placement on the registry might affect a person’s employment opportunities or their ability to provide caregiving services.

In late September, an independent watchdog released a critical report detailing gaps in Arizona's system for protecting its vulnerable adults. It pointed out that less than 1% of investigated reports of abuse, neglect or exploitation of all kinds were substantiated by Protective Services over the past three fiscal years — a rate far lower than the national average, which was 33% and 29% in 2020 and 2021, respectively, according to the report.

“I'm really struggling with this number of 1%,” said Meaghan Kramer, who represented the Arizona Center for Disability Law on the ad-hoc House Committee on Abuse and Neglect of Vulnerable Adults meeting in November. “You guys are all over the state telling people to call the number to report abuse and neglect, and I shudder.”

Members of the committee seemed disturbed by Adult Protective Services' inability to hold people who abuse, neglect and exploit vulnerable adults accountable. Molly McCarthy, the Department of Economic Security's assistant director for aging and adult services, did not acknowledge that Protective Services has systemic problems during the meeting. She instead repeated a refrain that the agency should not be compared to those in other states. She said the watchdog’s findings on substantiation were wrong.

Comparing substantiation rates between states is difficult because there’s no federal standard, McCarthy said. Arizona Adult Protective Services doesn’t count verified cases in its substantiation rate, and widening the agency’s definition to add them in would substantially increase that rate, she said.

But this isn’t the first report to note that Arizona's substantiation rate appears lower than that of other states. A review conducted for the federal Administration for Community Living added verified cases to its count of substantiated allegations in Arizona, but still found the state’s 2018 rate "substantially lower" than the national average that year.

Unless an allegation is substantiated and a person is placed on the registry, it’s difficult to find out whether they ever were investigated. The agency won't confirm or deny whether it ever has investigated anyone, citing a state law that makes its records confidential.

The result is an extreme lack of transparency: The public has little visibility into how the agency handles cases and no way to find out whether an incident was investigated.

“Transparency is not just a nice word. It’s the fundamental basis for accountability,” Caspi, the gerontologist and researcher, said.

Will anyone listen?

Police investigation into the Heritage Village resident’s claims quickly yielded evidence corroborating her story. In his police interview, Corral admitted to penetrating the woman.

She wanted to be with him, he said. He’d gone into her room to watch a movie — while he was still on shift — and one thing led to another.

An officer told Corral he “had a hard time believing” an 85-year-old woman who Corral cared for would seek him out, and the acts he performed on her left many painful injuries.

“Manuel had no real response other then to shake his head and look down,” the officer wrote.

The consequences for Corral began rolling in.

He was fired by Heritage Village and arrested on rape charges. He was indicted on eight counts of sexual assault for both his 2012 and 2020 crimes. He pleaded guilty to reduced charges: three counts of attempted sexual assault. He was sentenced to seven years in prison.

But there were scant consequences for Heritage Village and its management.

The Department of Health Services investigated a complaint detailing the assault — but its report makes no mention of what happened to the woman.

Instead, it cited the facility for an “inappropriate touching” allegation against Corral, made by another resident months before the sexual assault.

That citation was for the manager’s failure to ensure facility staff had the “qualifications, experience, skills and knowledge necessary to ensure the health and safety of a resident.”

Heritage Village was fined $500, and that was that.

In court documents filed after Corral pleaded guilty, the 2020 survivor’s son said dementia had taken many of his mother’s memories, but she still became angry when she recalled Corral’s assault.

He said he felt Heritage Village didn't look far enough back in Corral's employment history, allowing prior incidents to remain off its radar. He believed it was an injustice, one that would continue perpetuating itself “if state agencies and care facilities continue with current hiring practices.”

It was an injustice that left his mother powerless.

“I don’t remember ever crying — and I couldn’t holler,” she said. “I mean, who’s going to be listening?”

Arizona Republic reporter Caitlin McGlade contributed to this report.

Reach Sahana Jayaraman at Sahana.Jayaraman@gannett.com. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter, @SahanaJayaraman.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona senior care centers: Who gets punished for sexual assaults?