On Arizona's San Pedro River, hummingbirds reflect the health of a landscape

Water for the river:

Colorado River | San Pedro River | Gila River | Little Colorado River

SIERRA VISTA — Sheri Williamson blew on the feathers of the small hummingbird in her hand using a short blue straw. Next to her, a volunteer typed into a spreadsheet the bird's wing length, weight and sex, along with the five digits in the tiny numbered metal band on the bird’s leg.

A volunteer fed the hummingbird sugared water, and placed it on the extended palm of an 8-year-old spectator. The bird quivered, seemed to doze for a minute, and took flight.

Williamson, one of North America’s most renowned hummingbird experts, has been banding on the San Pedro River since 1996 with her husband and colleague, Tom Wood.

On that April afternoon at the San Pedro House visitor center, they banded just three hummingbirds and logged one recapture. The number was oddly low, even for the drop they’ve seen throughout the years.

"The numbers are down, the migration is spread out, the species' composition has changed somewhat,” said Wood, a wildlife biologist and professional birder.

The duo run the Southeastern Arizona Bird Observatory, a nonprofit operating in Hereford and Bisbee, and have banded roughly 10,000 hummingbirds.

The activity allows them and other professional birders to study hummingbirds’ migratory timing and routes, as well as the health of the population of different species. Data is shared with the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory, which has open banding records going back to the 1960s.

Blowing over the bird’s feathers, as Williamson did, reveals fat reservoirs, or the lack of them, an indicator of how prepared the bird is for the migration ahead. To get from point A to point B, hummingbirds, and hundreds of other species of migratory birds, need to find food and habitat along the way.

The San Pedro River, stretching from Sonora, Mexico, all the way north to the Gila River near Winkelman, is a critical “rest stop.” It is a flyway for half of all the bird diversity in North America.

“All the lovely birds that people enjoy seeing at their garden or in their local parks, or at their bird feeder” across the United States, “got there using resources like the San Pedro River to migrate north,” said Jennie MacFarland, coordinator of the Important Bird Areas program in Arizona, which includes portions of the San Pedro.

The quality of this important flyway has deteriorated in recent decades.

River surveys conducted by The Nature Conservancy during the driest month of the year show almost a 50% drop in the miles of "wet" river from 2009 to 2022. Today, less than 30 of the 173 miles of the San Pedro have surface water by June. The term "wet" is used because not all water encountered along the surveyed area is actually flowing.

The drop in water levels also means a change in habitat. For the birds, urban and farmland growth, wildfires, cattle grazing and groundwater pumping profoundly affect their migration and overall survival.

“If they can’t find what they need along the way, they're going to continue to decline,” said MacFarland.

'Up against a clock' for San Pedro's survival

Once perennial, the flow of the San Pedro River has weakened over the last century. It has thinned and disappeared in many sections, going underground.

Vegetation has changed due to a mix of deforestation, cattle grazing, groundwater pumping and extended droughts.

A main concern is the lack of “recruitment.” The cottonwood and willow gallery forests that line the river bank are aging, and the lack of new individuals presents a big challenge, said Kim Schonek, water program director for The Nature Conservancy. The nonprofit has been key in leading research, conservation and management programs along the river, and has led citizen river-mapping efforts for over 25 years, a project that allows them to watch trends.

This year, the Bureau of Land Management will conduct a vegetation survey, and assess the type and age of what grows along the river. That data will be incredibly valuable, Schonek said, because they can compare it with data obtained 20 years ago.

It will also improve estimates on the limit at which a low water table can still sustain healthy, verdant trees, and cottonwood gallery forests can survive.

“That is really the most important ecological threshold,” said Holly Richter, a hydrologist who has worked on the San Pedro River for nearly 25 years and has been key in establishing interagency partnerships in the upper basin.

The BLM will conduct the vegetation survey in the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, one of the Important Bird Areas of the river that has long been affected by trespassing cattle and groundwater pumping. The lower basin, near Winkelman, will not be included in the survey.

Federal agencies and the local city and county authorities entered a memorandum of understanding in 2021 that aimed to balance the water demands and the ecological needs of the river habitat.

In Richter's view it is not far-fetched to think people in Arizona could grow up never knowing a flowing river.

“We are up against the clock,” she said, adding that every river in the Southwest faces threats from climate change and groundwater pumping.

"I challenge people to go down to a river in the middle of summer at sunrise, when the birds are so loud that you can't talk to another person, and the wildlife is super abundant, and it is cool and beautiful and moist, and say that that is not important.

"I guess you can't love what you don't know.”

Warmer temperatures count disrupt 'road stops'

At the San Pedro House, a crowd of nearly 40 people packed under the ramada. Older adults wearing floppy hats and binoculars, some young couples and a handful of restless kids watched Williamson carefully measure and band the captured hummingbirds, using a big magnifying lens over the plastic table.

The first catch was a male Rufous hummingbird, a bird that “glows like a copper-penny,” Wood told spectators. They are less likely to be caught than other species. Their population has dropped about 60% since 1974, according to recent conservation reports.

Rufous are long-distance migrants that annually travel from their winter home in southern Mexico all the way to Canada and Alaska for breeding — nearly 4,000 miles.

That mileage requires a lot of travel stops. In Arizona, they usually arrive for a spring feast.

“The timing of the blooming of the wildflowers and the arrival of the hummingbirds has been set over the millennia,” Wood said, but there are concerns about the warming climate.

Blooming season changes with the temperature, and birds are still migrating in response to daylight, he added. If flowers bloom early, there are no birds to pollinate them, and if birds get there when flowers are gone, they get no fuel for the rest of the trip.

Wood and Williamson still don’t know if this change is happening too fast for hummingbirds to adapt. Overall, they have observed that hummingbirds are spreading the migratory season for about three extra months, arriving earlier, by late March, and leaving later, around early October.

The other big factor is habitat change and, sometimes, destruction.

“One of the challenges of conservation for migratory birds like these is that they not only gotta have a summer home up here, they gotta have a winter home in Mexico and too many stations all along the way,” Wood said. Conservation has to happen across numerous territories.

If they feed on a wildflower patch for five years and from one year to the other they find a Walmart parking lot instead, Wood said, they are in trouble.

The San Pedro River is important, Wood said, because it gives them “pretty much everything.” It remains a key water source and wildlife habitat in the middle of a desert, with the Rio Grande 200 miles to the east, and the Colorado River 250 miles to the west.

“It's easy just to think of it as a water source but it's also a source for the insects that they need to feed on, the flowers that provide nectar, the shelter from trees," Wood said. "Everything they need is on the river."

Restoring habitat in the lower San Pedro River

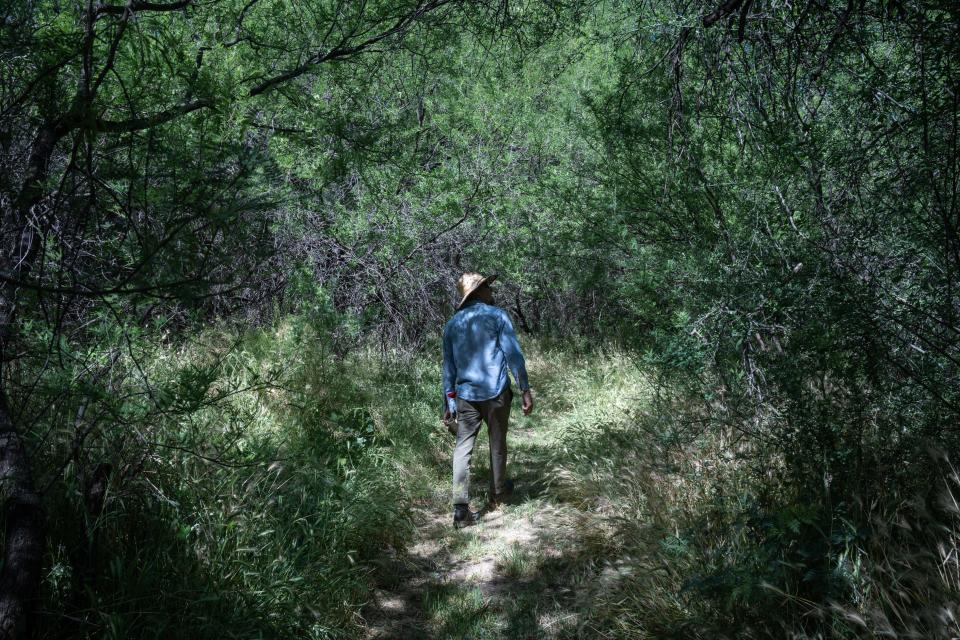

Some 100 miles north of the hummingbird banding grounds, the San Pedro River looks slightly different. Lower in elevation, the region is drier than the upper basin in Sierra Vista.

Water was found flowing above ground in only 6 miles along the lower basin in the hottest month of 2022, half what was in the upper basin, according to TNC’s mapping. The river bed — a dry wash with small water pools in many sections — has widened and has plenty of invasive salt cedar, also called tamarisk.

"It's getting to be this way increasingly, this is happening in more parts of the river,” said Dan Wolgast, who has been observing the changes in the lower San Pedro River for more than a decade.

He manages about 500 acres of land in the lower San Pedro River for Salt River Project. On these properties, the southwestern willow flycatcher and the yellow-billed cuckoo drive conservation and restoration work. Roosevelt, Horseshoe and Bartlett dams inundated habitat for the imperiled birds, so management plans focus on compensating for losses.

The SRP properties, previously used for farming, now have no groundwater pumping, providing a small counterweight to the region's water use.

Wolgast monitors and removes invasive plants to ensure habitat recovery and helps with big and small restoration efforts. In wide sections of the river, where last year’s rains created small pools of water, he planted about 20 willows. He expects those, and the cottonwood fluff lying all around, will thrive with the remaining moisture.

"We try as much as we can to let the habitat take the lead," Wolgast said. "We are here to protect it and provide small inputs."

On a different site, mesquite woodland has returned to a plot that was bare in 2011, before restoration work started. That property, with a blanket of desert brush extending a quarter mile toward the river, now has almost the same songbirds as properties with older woodlands, Wolgast said.

Wolgast is not a birder by training, but a good bird noticer. A pair of binoculars hung from his neck and he tilted his head to hear bird calls. In his home backyard in Dudleyville, aloe vera, gold poppies, penstemon, and glandularia flowers bloomed. An Anna's hummingbird fed on a pink wildflower as he spoke.

Revegetation is important because it allows birds and other wildlife species to make their way back into the area.

On SRP’s adobe preserve property, bird call was nearly deafening in the mesquite thicket. Taller trees — box elder, ash, cottonwood, walnut and sycamore — shaded the area. A shallow pool of water upwelled in a nearby wash, an anomaly in the past decade, and a product of last year's generous monsoon, Wolgast said.

“This area grows plants that you don't see almost anywhere else in this part of the river,” he said. "It's a lot of life just crammed into one area. It's neat."

Same river, different conservation challenges

Land ownership is probably one of the most important differences in conservation work in the lower and upper basin.

Near Sierra Vista, the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area is made of nearly 57,000 acres overseen by the Bureau of Land Management. The area where Wolgast works, near Dudleyville, is mainly private land, with a smattering of federal and state trust properties.

To conduct its annual river surveys, The Nature Conservancy must get permission from about 25 people to map a short section of the river. Researchers would like to learn both water flow and vegetation changes across the whole river.

“Without access to private lands, it's hard to say exactly what that looks like over time,” Schonek, the water program director, said.

The challenges are not just administrative, but also economic. Coordinating efforts with several agencies that oversee most of the riparian areas near Sierra Vista has administrative advantages, and it comes with funds.

“It’s very different when there aren't as many federal players at the table that can bring resources. And that's a major difference between the upper and lower river,” said Richter, who was a founding member of the Upper San Pedro Partnership and now acts as coordinator of the memorandum of understanding with federal agencies.

“There's a lot more private landowners in the lower river and they don't always have access to the resources of the federal agencies. That is a very real thing.”

On the other hand, these are unprecedented years for funding water conservation projects.

“In my lifetime there's never been such a wealth of funding opportunities coming down the pipe as there is right now,” Richter said.

The caveat is that there needs to be more people coming to the table and finding common ground, because “you can't get funding successfully without collaboration,” she said.

Clara Migoya covers environmental issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to clara.migoya@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

You can support environmental journalism in Arizona by subscribing to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Hummingbird migration could help track health of San Pedro River