As Arizona's water infrastructure crumbles, small-town residents face skyrocketing utility fees

The small desert town of Ajo, one of the last stops on State Route 85 before the Mexican border, was once a “company town” largely built by the owner of the nearby copper mine.

To this day, residents like to say they live in “miner’s shacks” — compact houses erected for the workers who toiled in the open pit mines. Bigger more desirable homes in town once were occupied by mine supervisors or coaches of the high school sports teams, residents say.

But for more than 1,000 of the town's residents, the mine’s legacy now stands not in the places where they rest their heads or the perpetually sputtering economy since the mine closed, but from exploding utility bills.

Residents hadn’t had an increase in their electric rates since 2000 and their water and sewer rates were last raised in 2004.

While the absence of rate increases sounds great in theory, the utilities were dying without maintenance and investment – residents complained about dayslong power outages from storms and poorly constructed 100-year-old sewers allowing open sewage to pool in places.

Global mining giant Freeport McMoRan Inc. bought the company that owned the mine — Phelps Dodge — in 2007 and the sale included the town utility: Ajo Improvement District.

State utility regulators at the Arizona Corporation Commission were caught off guard by the shocking 500% rate increase the company requested in 2017 to pay for the upgrades Freeport made to the system since buying the mine.

Freeport said it paid $48 million to fix the system, even though those fixes were not approved by the Corporation Commission. Utility rates are typically set using a formula that takes into account how much money has been spent on projects the Corporation Commission deems reasonable, which is divided by the number of customers and the amount of water or power they consume in a year.

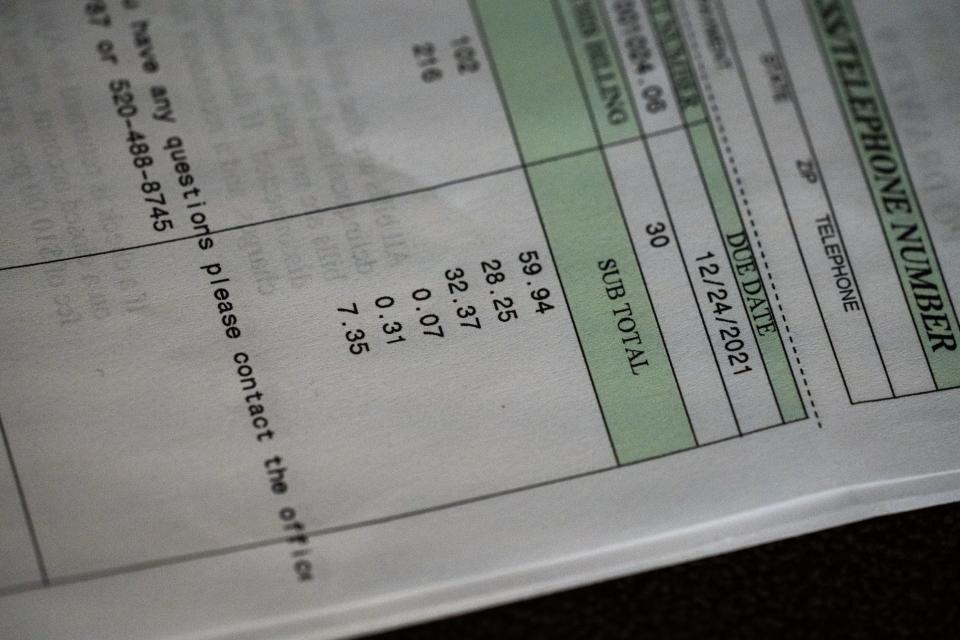

Residents rallied to fight the increases, which were lowered by the Corporation Commission and phased in over 10 years. But they still sting — a 109% increase in electric rates, a 372% increase in wastewater rates and a 256% increase in water rates.

All told, residents' combined bills will rise from an average of about $80 a month to about $236 a month — nearly tripling bills over 10 years.

And the utility will surely be back for more after the rate increases are fully phased in, said Robert Sorrels, who led the desert community’s fight against the utility increases. “Absolutely, after 10 years they will be back for more money,” he said.

Despite the rate increases digging into his limited budget, Sorrels says he feels lucky. He knows there are other people in town who simply can’t afford it. He said many moved in with family or moved on.

“There are a lot of people in town with no hope,” he said. “They are focused on staying alive.”

One resident, who preferred not to give his name, is already paying more than the average. Retired from the Coast Guard and living on his pension and social security, he said his combined utility bill went up from $180 a month last year to $277 this year. Much of the increase is water.

“I try to cut back, take less showers, wash the clothes less,” he said. He has stopped watering outside plants as much and has a big blue barrel in the back to catch the rain.

The price hikes and high stakes are not unique to Ajo. They are playing out all over the Grand Canyon State. And they are playing out in the midst of an historic drought in which water from the Colorado River, which supplies 40% of Arizona’s needs, is shrinking, while groundwater reserves are in decline. In 85% of the state, groundwater is essentially unprotected.

Near Roosevelt Lake northeast of Globe, customers' water rates spiked by 60%, but the work to upgrade their utility was not completed, leaving them with water some are afraid to drink.

In Bouse, just north of Interstate 10 near the California border, residents spent nearly five years trying to take over the town co-op that delivers water that contains too much arsenic and fluoride.

In Pine and Strawberry, 15 miles northeast of Payson, the local water utility stopped issuing permits for new construction because its groundwater wells are tapping out from overuse and it is losing too much water through leaky pipes. Despite receiving a $1.5 million grant from the federal government and $25 million in loans, problems have only been partially fixed.

In a monthslong review of utility records and commission filings, The Arizona Republic found there are more than 200 rural utilities throughout Arizona in a similar position. These utilities serve tens of thousands of customers.

Most are regulated by the Arizona Corporation Commission, where it can cost tens of thousands of dollars to get a rate hike because it means hiring a lawyer and an auditor to certify the books. Many utilities feel they can’t afford the process and just keep the same rates and infrastructure until their equipment fails and it is too late.

Despite knowing about the water problems for decades, the Corporation Commission has done little to remedy the situation. That has left rural Arizonans to face financial ruin or a future without water.

Many small water districts were formed either by homesteaders who drilled a well and started serving others, are rural mobile home parks, or were formed by sketchy land developers. They are essentially water companies by default.

Many of these utilities came together decades ago and are in decrepit conditions because the owners haven’t kept them up. Some are still charging the same water rates from more than 30 years ago. They haven’t invested in their utilities and are facing millions in upgrades when their infrastructure fails.

But Arizona law says that money has to be paid by the utility’s customers. Some of these utilities only serve a few dozen people — meaning those millions in upgrades can only be spread out over a few residents.

Many of those affected live on fixed incomes and moved into rural areas because it was the only place they could live comfortably. Many had no idea about the scope of the problems when they purchased their properties.

Now the potential lack of water imperils the only assets that many of them have — their homes.

Arizona Corporation Commission: Hardly a success

Corporation Commission members over the past several years have recognized the problem and sought to fix it. But helping dozens of small businesses find financial stability is no small task.

In March 2020, Commission Chairwoman Lea Márquez Peterson invited more than 70 water companies that hadn’t adjusted their rates in 20 or more years to a special meeting where they could explain the challenges facing their businesses and why they had avoided filing for rate increases.

“We went through every one of those companies one by one to discuss why,” she said. “Every one has a particular story. Whether it was passed down through the generations, or an HOA runs it, or it's volunteers.”

Commissioners have tried to make filing a rate case easier for small water companies. And an ombudsman office helps small water companies that want to sell or otherwise get out of the business.

The commission has had luck with larger water companies purchasing smaller, struggling companies. But there’s not a good business case for those larger companies to take on every troubled utility.

“Usually the mayors or council members I meet with around the entire state, that’s one of their greatest concerns is a small water utility in their community they want to ensure is viable and is serving their customers,” Márquez Peterson said.

Despite these efforts, water utilities in rural areas are facing the same problems they faced 20 years ago. So you can hardly look at what the Corporation Commission or other actors in the state have been doing and call it a success, according to Paul Walker, who runs a Phoenix consulting firm — Theseus LLC — that advises energy and water utilities on financial and regulatory matters.

Arizona is now among the worst states in the country in terms of having a good economic environment for investing in water or power companies, according to S&P Global. And that matters, Walker said, because having a bad investment climate is like having a bad credit rating for an individual.

He points to scores of reports by U.S. and Canadian banks that are deeply critical of the Commission's approach to ratemaking, quoting an analyst from Guggenheim Partners who said the Commission's consistently short-sighted policies have driven up rates and borrowing costs.

Part of the problem, Walker continued, is that the Commission has been historically underfunded.

“A Bank of America analyst said it best a few years ago: Arizona has one of the smallest public utility commissions in America in terms of staff and one the busiest dockets in terms of workload.”

The Corporation Commission, however, never asks the legislature for more money, Walker said.

“I know people at dozens of utilities in Arizona and I’ve never met anyone who was against more money for Corp. Comm.,” he said. “The commission is fixated on being lean, on spending money on things that are truly important for safety and economic growth. But I would challenge anyone to tell me if there were two things more important than water and power.

“Arizona is a really hot and dry place.”

Nick Myers, who has worked as a policy adviser for Corporation Commissioner Justin Olson since 2021 and was elected to a seat on the board in November, says the fundamental problem with the commission is that commissioners have lacked experience in water issues and have seen the post as more of a stepping stone to something else.

“If commissioners didn’t have any concept of there being a problem, that was because staff wasn’t checking on companies in rural areas,” Myers said. “That, in turn, might be a staffing issue. We now have 50 to 60 full-time positions that are vacant.”

Myers got interested in the commission after his own experience as a customer of one of the most notorious water companies in the state, the former Johnson Utilities. Regulators eventually forced the sale of that water and sewer company.

Myers said his goal is to get staff out to rural areas, find out why utilities may be struggling and encourage them to come in to evaluate their rates.

“The commission needs to be more proactive than reactive,” he said.

Perhaps the biggest issues that small rural utilities encounter is that when their systems break down they don’t have enough paying customers to afford the fixes.

If you have 200 customers and a pump goes down, you’re looking at $30,000, explained Gary Saiter, who heads a domestic water improvement district in the western Arizona town of Wenden.

“That's a lot of money. And we have had them here go down several times in a single year for a variety of reasons — lightning strikes and things like that.”

Suddenly you have about $95,000 in additional costs that has to be spread out over 200 people. That’s about $40 per person each month.

The electric bill for the utility is $1,200 a month. Then there are the salaries of part-time employees. Every time you have to replace an arsenic removal system it’s $40,000 to $50,000. And a decent well — about 300 feet deep — is going to cost $750,000 to $800,000.

“People don’t really realize exactly how expensive it is to deliver water to your faucet every time you turn it on,” Saiter said.

When a 30- or 40-year-old system, which has not been maintained, starts breaking down, the costs just escalate. Utilities need loans or grants or a combination of the two to cover the overhaul.

“Eventually, the amount of money from loans will have to be paid back by the ratepayers,” Saiter said. “The grant money is free.”

The Corporation Commissioners were not always aware of which communities were in trouble until those communities came to them with their problems. But one way to find out is to see how long a water company has gone since its last rate hike.

According to data obtained by The Republic, there are more than 100 water companies in Arizona that have gone without a rate hike since 2001.

Though customers might be pleased about steady rates, the lack of increases may obscure the fact that utilities have done nothing to upgrade their infrastructure, and water may be pouring into the ground through leaky pipes.

Coming up with the money to help water companies make necessary fixes after years of neglect is the next hurdle. Fortunately, funding is available from the USDA, the recently passed Biden infrastructure bill, and Arizona's Water Infrastructure Finance Authority.

That still doesn’t help people like Teri Ryan who moved to Arizona from California and is now facing triple-digit increases in utility rates because Ajo’s utility company decided to make decades of deferred improvements all at once.

When she retired in 2010, Ajo seemed like a perfect place to get away.

“Everyone is looking for one thing when they leave a big city, to control costs and get a handle on things,” Ryan said.

She said the rate hikes in Ajo have affected her finances because she’s retired and living on a fixed income, and she's seen a change in the town.

“I think there were people who were on the edge before and they left,” she said. The increases were “really a problem for a lot of people."

Driving around Ajo, you can see residents with windows open in the summer even as the heat is above 110 degrees. Some houses will always have a fan set up in the door, indicating they aren’t able to use the AC despite the summer heat.

“The system is wrong in the way it has been set up,” Ryan said. “Everything has become for profit. Basic services should not be for profit.”

Strawberry and Pine: Vacation overload

A hundred miles north of Phoenix, beneath a canopy of Ponderosa pines and Douglas fir, Pine and Strawberry cling to the Mogollon Rim.

The area supported Indigenous communities and appealed to Mormon pioneers due to the abundance of life-giving streams. But now the towns, which provide shelter to anywhere from 8,000 to 12,000 residents and short-term renters on a given weekend, don't have enough water to go around.

Like hundreds of other rural communities in Arizona, the water infrastructure in Pine and Strawberry is falling apart. Every year the towns lose 30 to 40 million gallons, nearly a third of the total pumped, to leaky pipes.

But what makes the situation so much worse is that wells are now running dry.

Ask Rene Del Valle, the owner of Moose Mountain Gifts & Antiques, to explain what’s going on and he’s quick to blame COVID and Airbnbs.

A marketing major at college, Del Valle said that when the pandemic hit in 2020, city dwellers — afraid for their safety — hightailed it out of Phoenix and began working remotely from places like Pine and Strawberry. That meant the population in the two towns, which used to swell from 3,000 to 8,000 in the summer, remains high year-round.

Add to that the Airbnb phenomenon and demand for housing — and in turn water — began to exceed supply. Pine and Strawberry were suddenly using far more water than could be replenished by snowmelt or monsoon rains.

“Before, people only used their vacation homes occasionally — just for the summer months,” Del Valle said. “But now they’re using them all the time and some visitors don’t care about being thrifty.”

In Pine alone, developers bought up 275 of the 1,700 homes and converted them to vacation rentals, De Valle said. But while the well-heeled weekend visitors have been good for his business, they’re draining the aquifers.

Just 14 of Pine and Strawberry’s 38 relatively shallow wells are functioning at the moment, according to a presentation to the town and elected officials by Chris Ray, a concerned citizen. In turn, only two of the region’s eight deep wells, which go down as far as 2,000 feet and cost about $2 million each to dig, are drawing water.

Pointing to “older estimates,” Ray’s presentation states that it would cost Pine and Strawberry $135 million, or about $42,000 for each home and business in the area, to dig five deep wells, replace all the broken pipes and erect the necessary storage facilities and pumping stations to completely renovate the system.

Strawberry and Pine have nowhere near that amount of money, Ray said. The main utility — Pine Strawberry Water Improvement District — already spends 80% of its budget on fixing pipes and they’ve borrowed about $25 million more.

“They are maxed out on USDA loans,” Ray said. “They can only do so much replacement.”

Early this year, the towns declared a moratorium on new development to preserve what little water they have left. Anyone with a meter is fine, but no new meters are being given out.

For some residents, the crisis is particularly acute. Those with homes in the Portals, the toniest subdivisions with views out over the valley, have it worse than anyone. Houses in Portal I and II are connected to shoddy pipes that are now disintegrating.

“They’re constantly shutting the water off because another pipe is broken,” said Sonnie Hemphill, a resident of Portal II who works as a cashier at the Pine Strawberry Thrift Shop. “There’s so much calcium in the water that it’s not fit for a human being to drink. I buy bottled water because I refuse to drink it.”

Hemphill added that she’s only been in town for three years, but her monthly water bill keeps climbing — from $48 to $62 — because of all the broken pipes and loss of water.

Others in town, like Tom Hashem, say Pine and Strawberry have always had water problems.

His family moved to the area from Buffalo in 1958. They built a cabin just up the hill from Pine’s main strip.

“There would be leaks in the lines and a lot of water would go into the ground,” Hashem said. “Maybe we’d get water and maybe we wouldn’t. One year, they had to bring a tanker in for people.”

Hashem said it wouldn’t be fair to ask people to pay more to fix the system.

“There’s only so much you can burden people with,” he said. “You can’t take 40 to 50 years of neglect and expect to repair it all at once.”

Few people in town blame the Pine Strawberry Water Improvement District for the problems. They say current management responds quickly when it comes to fixing broken pipes.

The solution, just to meet existing needs, they say, is to find outside funding.

Both Ray, the concerned citizen, and Tom Reski, the former vice chairman of the Pine Strawberry Water Improvement District, hope assistance will come from either state government or from money that’s earmarked under the Biden infrastructure bill that U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema helped broker last year.

What Pine and Strawberry need, Reski says, is a pipeline to the C.C. Cragin Reservoir about 20 miles to the north and the permission to pump at least 265 acre-feet per year — enough water to supply 530 existing homes and to cover current shortages.

The towns would also need to build a treatment plant at a combined cost of $85 million, Reski said, and the only way to finance that would be through a grant.

Despite the fact that the region voted overwhelmingly for extreme government critics Kari Lake and Blake Masters, and Trump 2024 flags fly proudly in more than a few front yards, Reski wants Pine and Strawberry to tap grant money under Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

Sen. Sinema helped get that bill passed, Reski said, and $4 billion was set aside to mitigate drought in Arizona and other western states.

"That money has not been spent," he said.

Roosevelt: Even dogs don't drink the water

Sixty-five miles to the south, a mobile park nestles against the base of a mesa at the tip of Lake Roosevelt.

While the roughly 200 homeowners in the park are free to fish, swim and boat around in the lake’s ultramarine waters, they’re not permitted to pump any of it into their homes for drinking, showering or washing their clothes.

That’s because Lake Roosevelt’s water rights belong to property owners far down in the Valley.

In Roosevelt Estates and the several other mobile home parks in the area, residents are relegated to drawing water from wells that lie downstream from some of the largest copper mines in the world.

The owner of the water utilities — Colorado businessman Jason Williamson — has posted documents from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality on his companies’ websites certifying that the water has been tested and is safe to drink. But some residents aren’t sure whether to trust them.

The system is 40 to 50 years old, explained Ginger Somers, who spends part of the year in Roosevelt Estates and part of the year in the mountains of Pinetop, 75 miles to the northeast. The galvanized iron pipes are rusted out, which causes the water to come out of the tap orangey brown at times. It’s full of lime, she says, which corrodes water heaters, forcing expensive replacements.

Somers worries that the water could be bad for health — that it may even be responsible for the four people who died of cancer in the neighborhood over the past five years.

“I don’t let my dogs drink the water,” she said.

Dave Watkins, another resident in the subdivision, agreed.

“Just try washing your car,” he said. “The water leaves it streaked and stained.”

He added that he only uses it to shower, but wishes he didn’t have to because it makes you itch and leaves crud on your towels.

“If I could figure out how to shower out of a five-gallon bucket, I would do that,” he said.

The Corporation Commission permitted Williamson’s company to increase rates by 60% eight years ago and Somers said residents were expecting the company to start fixing the deteriorating infrastructure back then. But she said the company didn't make any repairs until reporters from The Republic showed up and started asking questions six months ago.

Then, all of a sudden, Tonto Basin Water Co. began laying pipes and installing new water meters.

“Things have done a 180 in terms of service,” said Jim Lavery, a former fire department captain who lives in the subdivision. “I don’t know whether they knew you were coming. But they’ve done a phenomenal job of giving me service again.”

Lavery said he lost water pressure in his home and complained to Gila County. The utility sent men out to work on the problem, promptly installing a new meter and a new pipe under the road.

“I can now flush the toilet and wash my hands at the same time,” Lavery said. “I can pressure wash the cat boxes."

Reached by phone in Colorado, Williamson said his company has never had an issue with water quality. He added that infrastructure projects take years to develop.

This one at Roosevelt Lakes has been in the works for two and a half years, he said. It entails changing out all the meters, replacing the galvanized iron pipes and digging a new well.

Williamson said that everything should be done by the end of the year and he has already filed for a rate increase in November which “will more than double water rates, if we’re given what we’ve asked for.”

For Somers, that means her bill will go up from around $50 a month to over $100. She pays $35 a month in Pinetop, which is in Navajo County. Some of her neighbors in Roosevelt Estates will see their monthly bills go up from $32 to around $70.

The average monthly water bill in the United States is $45, according to move.org, a moving resource site.

“There are people in this subdivision who are living on retirement incomes who are just getting by day to day,” Somers said. “They don’t have an extra stash of money lying around.”

Williamson countered that improvements to the water system will increase property values.

“Our goal is to create a more reliable water service,” he said.

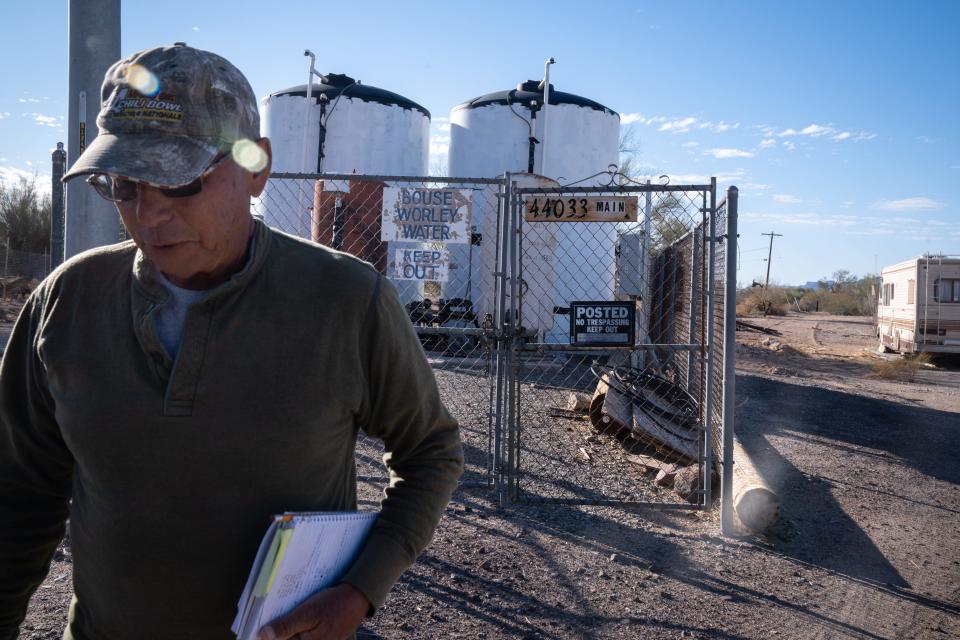

Bouse: A rare water solution

Two hundred and fifty miles West near the Colorado River, in Bouse, a desert community of nearly 1,200 residents, problems revolve around the big agricultural producers that are sucking water out the aquifers. In most rural areas in Arizona groundwater is unregulated.

Residents also have to deal with high concentrations of arsenic and fluoride that require the replacement of expensive filtration systems every three or four years.

Residents on individual wells say they’re terrified that companies like Fondomonte, the Saudi alfalfa operation in Vicksburg, or Rose Acre Farms, the industrial egg farm just 10 miles up the road, will draw down the water table so far that homeowners will no longer be able to reach it.

Residents would then have to spend tens of thousands of dollars to dig new wells. But with a median income of just $17,000 — much lower than in Pine, Strawberry, Ajo or Roosevelt — such outlays would be nearly impossible.

So if wells run dry in Bouse, likely as not, residents will either have to sell their manufactured homes or hook them to the back of their pickups and head on down the road.

David Franks, a retiree whose home is attached to the town’s utility system, faces similar concerns.

Not only is the utility’s well relatively shallow and in danger of drying up, but it also has to deal with crumbling pipes and the need to install arsenic filtration systems to meet environmental regulations.

“ADEQ was on us in a real bad way and threatening to shut us down and fine us,” said Franks, who heads a community effort to solve the local water crisis. “Being as small as we are — roughly 150 taps — we just aren’t generating enough revenue to take care of ourselves.”

Franks added that residents aren’t allowed to drink the water because of the arsenic and fluoride levels. There’s even a sign in the Ocotillo Lodge in town warning customers not to imbibe.

But rather than give up in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Franks and a group of fellow retirees managed to achieve the impossible.

After five years of hard work, which involved the intensely bureaucratic process of converting their utility from a co-op to a domestic water improvement district, they finally managed to raise about $6.5 million to fix their dilapidated water system. The money will take care of digging a new 350-foot well, installing a 70,000-gallon water tank, replacing undersized water lines with larger pipes and setting up drive-by meters at every house.

Franks said they won’t have to build an office building because their lone maintenance man and sole administrator have agreed to work out of their homes.

Best of all, most of the nearly $7 million they raised won’t have to be repaid because all but about $400,000 came in the form of USDA grants. That means the funding won’t be as much of a burden to a community of retirees living on fixed incomes as loans alone would have been.

Rates will go up about $10 from the $35 a month residents are paying now, according to John Bennett, who handles maintenance for the utility. But they won’t double, which is what everyone was fearing as recently as last summer.

Now with the meters that are being installed, residents will be able to regulate the water they use and the amount they shell out every month.

“We’ve gotten rid of a lot of trees and shrubs,” said Michaella Ames, a former member of the water task force, as she looked out her kitchen window onto a butterfly garden and a couple of birds pecking away at a cube of bird seed. “It’s only fair that you pay for what you use.

“Everybody is on a fixed income here whether you work or whether you’re retired,” she continued. “All of us have to have priorities with our money — and water is a priority.”

Unfortunately, however, Bouse is a rarity: a small rural town that had enough concerned citizens to battle their way through a bureaucratic and financial maze to find an affordable, long-term solution for their water problems.

Reaching the same solution in similar towns across Arizona is only going to come when Arizonans accept the reality that the state is “hot, highly populated, growing every day and we don't have a long-term water solution,” said Walker, the energy and water consultant.

“Investors and creators have to solve it,” he said. “God won't magically make it rain and snow, and neither will Big Government. We have to use the water we have in much, much smarter ways — and that's going to cost money.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Arizona towns face higher utility bills as water infrastructure fails