Armadillos and javelinas are Texas icons, but they haven't been here as long as you think

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

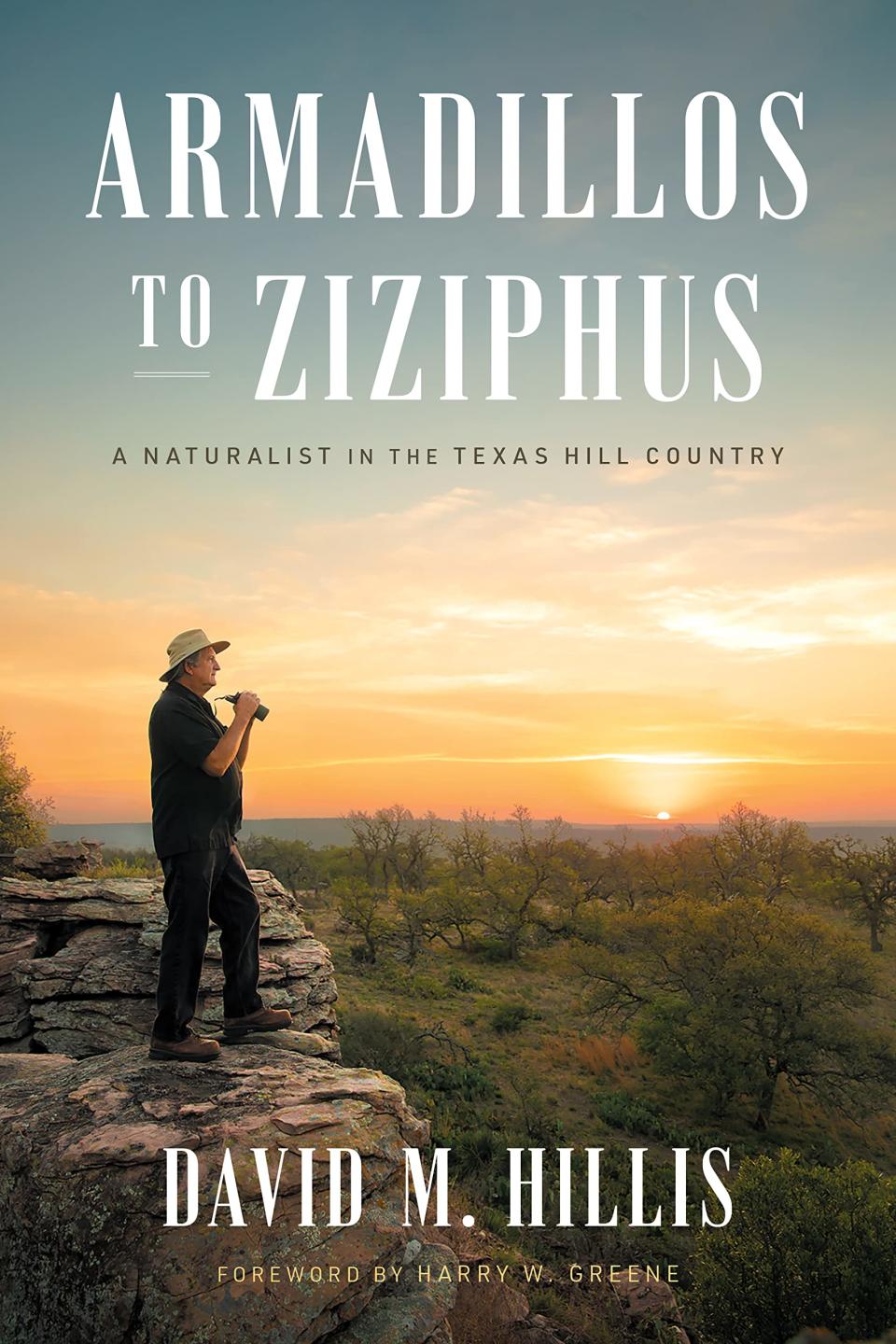

One of the most practical and pleasing new Texas books of 2023 is "Armadillos to Ziziphus: A Naturalist in the Texas Hill Country" (University of Texas Press).

Written by David M. Hillis, director of UT's Biodiversity Center, the volume consists of 54 brisk essays about nature, especially as observed in the Hill Country on or near the author's Double Helix Ranch in Mason County.

Hillis is one of those polymaths who has figured out how to talk easily and elegantly to the public about almost any subject that crosses his path.

More: Biodiversity along Texas highways, then and now

At the same time, Hillis is prized among his science peers. He was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1999 and was elected to the U.S. Academy of Sciences in 2008. He has discovered quite a few new species, including the shy Barton Springs salamander, whose endangered status has helped preserve great swaths of the Barton Creek watershed.

Some of his essays are almost purely descriptive and can take in the expanse of the Edwards Plateau. Others focus on small worlds, such as the vernal pools whose life adjusts to the wet and dry seasons of the Hill Country. He writes assiduously about the interconnected rivers, springs, caves and aquifers as well as the evolving nature of the region's grasslands, woodlands and brushlands.

Hillis is serious about his science but he pauses to thrill at the beauty of nature. His final two chapters are devoted to climate change and the future of Hill Country's resources, which he believes can be preserved through thoughtful stewardship.

The "ziziphus" of the title, by the way, refers to the lotebush (ziziphus obtusifolia), a species of thorny brush that one Hill Country landowner wanted to eliminate entirely.

"I explained that some scattered clumps of thorny lotebush were exactly what he needed for quail," Hillis writes. "Quail seek out lotebush because it is so spiny; those spines keep predators from attacking quail as they rest. Remove the lotebush, and the quail would have no place to hide from hawks and other predators.

"As we drove around and looked at other native vegetation, he seemed surprised to learn that much of what we identified and discussed had beneficial qualities that might not seem obvious at first. In addition to providing effective wildlife cover, lotebush also produces small black fruits that are relished by both quail and deer."

I will read these incandescent essays — many of them previously published in the Mason County News — again and again. But first allow me to share, with the explicit permission of the author and the publisher, one essay that grabbed my attention right away.

'Some Texas Icons Haven't Been Here All That Long'

When you think about iconic Texas animals, the nine-banded armadillo and the collared peccary (also known as a javelina) are probably high on your mental list. But did you know that both of these animals are relatively recent immigrants to Texas?

In 1880, a biologist by the name of Edward Drinker Cope wrote a paper, published by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., titled “On the Zoological Position of Texas.” The point of the paper was to determine the boundaries of the major biological realms of North America — where east meets west and north meets south.

Cope reasoned that these boundaries must lie in Texas, and he visited the state in the late 1870s to see for himself. He traveled throughout Texas, and on one trip left San Antonio, taking what was then the main road west, which took him across the Edwards Plateau to near the headwaters of the Llano River, south of present-day Junction.

More: Texas History: Take a cool dip into the historic Medina River with this detailed guide

Why should we be interested in Cope’s paper, written nearly a century and a half ago? It provides a fascinating window into the many changes that have occurred to the fauna of Texas, in the course of just a few human generations.

For example, Cope reported that jaguars were “not rare” along the Nueces, Medina and Guadalupe rivers, and he saw many skins of locally killed jaguars for sale in San Antonio. He reported ocelots to be even more abundant and widely distributed than jaguars, and he found them to be “common” near Fredericksburg. He noted that mountain lions were common “all over Texas.”

Although Cope saw many mammals — like the wild cats mentioned above — that we now consider rare or extinct in Texas, he never saw an armadillo here, although he heard a report of one in Frio City (now Frio Town), in South Texas.

In fact, armadillos had only recently moved north into Texas from Mexico when Cope made his surveys of Texas in the latter part of the 19th century. Cope did see collared peccaries, another iconic Texas mammal that moved north into our state only in the 1700s.

Both armadillos and javelinas are among the many animals that moved between North and South America as part of the Great American Interchange, a shift that occurred when the Panamanian Isthmus formed between the two continents nearly 3 million years ago.

More: Area's armadillos deserve more than symbolic homage

Once a land bridge connected North and South America, many animals moved in both directions between the two continents. In addition to armadillos, opossums and porcupines also moved north into North America from South America. Even more mammals — including jaguars and other cats, as well as peccaries — moved from North America into South America than moved in the opposite direction.

Although armadillos entered Central America millions of years ago, it wasn’t until the 1800s that the nine-banded armadillo made it as far north as Texas. Human agriculture and other human modifications of habitat almost certainly aided the expansion of armadillos northward and eastward, and they have continued to expand their range.

In their original tropical range in the Americas, armadillos rely heavily on a diet of ants. As they moved northward, however, they expanded their diet to include a broader array of small invertebrates and even some plants. That was an important adaptation, because a diet of ants would not allow armadillos to survive our northern winters.

Diversifying their diets allowed armadillos to find food sources year-round and to put on enough fat to survive periods of inactivity during the coldest periods of the year. A study published in 2019 showed that the armadillo skull structure in recently invaded regions of North America has also evolved in a number of ways that are likely associated with the increased diversity in the animals’ diets.

More: Can you get leprosy from armadillos? The unusual history behind a Texas icon

Armadillos are fascinating for many other reasons as well.

One of the most interesting aspects of their biology is that armadillo offspring are typically identical quadruplets. The four siblings are only about three ounces each when born. After the young are born, usually in March, they stay in the burrow for the first three months of life, living only on their mother’s milk. Sometime in June, they finally emerge and forage with the mother, staying with her for the rest of the summer and fall. By the time they reach one year old, they are independent and foraging on their own.

Armadillos are protected by a shell that consists of bony plates covered with scutes, which leads many people to mistake them for reptiles rather than mammals. But if you turn an armadillo over, you will see that its undersides are covered in rough hair, and as we have already noted, they produce milk like other mammals and give birth to live young.

The shell of an armadillo makes the animal heavier than water, so armadillos don’t swim. Instead, they cross streams and rivers by holding their breath and walking across the bottom of the riverbed. It is startling to follow an armadillo and watch it enter a water body and walk across the bottom.

Armadillos don’t see well at distances, which allows potential predators to approach them closely before the armadillo reacts. When they sense danger, they may leap straight up in the air to escape. This is an unfortunate adaptation if the perceived danger is a passing car or truck; many an armadillo leaps to its death as it is hit by a passing vehicle. Once an armadillo is alarmed, it can move at surprising speeds to escape.

When I see an armadillo out and about on the Double Helix, I often try to approach it slowly and quietly from the rear, which allows me to follow it unnoticed as it forages. On several occasions, I’ve watched armadillos gathering leaves and other materials for their nests, which is quite a funny sight to behold.

While holding the nesting material between its fore and hind limbs, the armadillo will hop backward to the nest in a highly comical manner. If you don’t make any sudden movements, the armadillo is likely to smell you before it sees you. If you continue watching in this manner, you can follow an armadillo closely for many minutes before it senses your presence, and you will likely gain an increased understanding and enjoyment of this Texas icon.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletters page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: How to learn about Texas Hill Country: Read 'Armadillos to Ziziphus'