For the Army-Navy game, once the biggest in football, one team's fans will be on a mission

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the nationally televised, 123-year football series between the nation’s two oldest service academies, Navy has won more times.

But Army, now known as the Black Knights, has a psychological weapon that many of its fans, including several from Michigan with tickets to the game, plan to deploy this week that shows just how deep the football rivalry is woven into the nation's history.

At one time — before Michigan State was a member of the Big Ten Conference, before there were color TVs to watch sports, and before there was the Super Bowl and College Football Playoff Committee — the Army-Navy game was America’s most important annual gridiron contest.

And back then, the academy teams were among the best in the nation.

In more recent years, both teams have faced changes in college football that have made it difficult to compete with powerhouse universities with more academic, eligibility and recruiting flexibility. And next year, Army and Navy will both be in the American Athletic Conference, which could bring more complications.

But the conference has promised the rivalry game will continue to be played during the second weekend in December; although, it may be possible that the two teams could play twice, if the programs finished first and second in the AAC.

What hasn't changed — and some say never will — is the game’s pageantry and deeper meaning because it is much more than a football game.

Most years, the game has been played in Philadelphia, the city where the Declaration of Independence was signed, and neutral territory. This year, the game starts at 3 p.m. Saturday just outside Boston in Gillette Stadium, the home of the New England Patriots.

CBS plans to nationally broadcast the skirmish, which is set to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party and — for the Navy fans — the 225th anniversary of the first voyage of the USS Constitution.

To fans, the rivalry game is as important as ever.

'Rangers lead the way'

Now, about that weapon.

It is tied to an old taunt — and relatively new Internet meme — that goes like this: " 'Let’s play Navy!' Said no kid ever." The only Navy game kids played had an earwig advertising slogan: "You sank my battleship!"

To remind fans on the other side of the stadium of that, Army fans plan to leave little, green infantrymen — like the kind that came in the Bucket O Soldiers in the movie "Toy Story" — everywhere they go.

"Last year, when we went to the Army-Navy game, we’d find these guys," Rosemarie Merten, 62, recently said, nodding to a pile of toy Army men on the kitchen countertop of her Royal Oak home. She turned to her husband, Tom, and added: "Then, we found out the story behind them, and we said, 'We need to get some for next time.' "

Army — in what their fans would agree was an exhilarating and unexpected victory — won, 20-17, in double overtime.

Will the team repeat? For more than a week, now, cadets and midshipmen have been trash-talking. In some years, they’ve carried out some elaborate pranks, which, in academy-speak are called "spirit missions." They’ve nabbed each other’s mascots. Navy has Bill the Goat. Army has mules. And more.

On social media, Army and Navy fans, which often includes enlisted folks who never went to college, are trading digs. A new meme this year shows celebrity Kansas City Chief tight end Travis Kelce saying "Beat Army!" In response, Army fans posted a photo of Kelce love interest and superstar singer Taylor Swift, saying "Beat Navy!"

More: The All Academy Ball, a long-standing annual military tradition in Michigan is returning

The Mertens — the children of veterans — are strategizing where to put their soldiers as they head to Boston. In late October while visiting their son, who is a cadet at the military academy, they bought a bag of plastic soldiers during Family Weekend at one of the gift shops.

Where will they deploy them?

"Definitely at the airport, on the plane, maybe in the Uber on the way over, and the hotel — for sure." Tom Merten, 58, said. "And then probably at the pep rally Friday night, where all the parents, old grads and supporters get together to get pumped up."

The toy soldiers, they hope, will mess with the other side's heads.

Among the real soldiers, the infantry’s motto is "Follow me!" And "Rangers lead the way."

Battle for bragging rights

The football rivalry aside, the Army-Navy game — often called "America’s Game" — has a long history.

President Thomas Jefferson established West Point — so named because of a point that jutted out in the Hudson River in New York — as the nation’s military academy in 1801. The Naval Academy, known as the Yard, was created next in 1845 in Annapolis, Maryland.

And on Nov. 29, 1890, the two academies held their first football game.

The story goes that Cadet Dennis Michie, for whom the West Point stadium is named, accepted a challenge by a group of Naval Academy midshipmen. Navy won — and the rivalry was born.

In 1926, Navy won a national championship.

In 1944, Gen. George Marshall, the Army chief of staff during World War II, purportedly said he wanted "an officer for a secret and dangerous mission," specifically "a West Point football player." His words, now on a plaque that the Army players touch before games, are a rallying cry.

A year after that, the game was nationally televised and has been every year since.

In 1946, West Point won what it considers its third, and probably its last, national title. And in 1999, the academy officially adopted the team nickname Black Knights, shorted from "Black Knights of the Hudson" because of the dark uniforms they initially wore.

As for the Army-Naval football rivalry now, USA Today ranks it among the nation’s top three, just behind Michigan-Ohio State and Auburn-Alabama, calling the game one of college football’s "most enduring" matchups.

Athleticism and patriotism

In addition to football, game spectators witness America’s military might: jets and helicopters zooming across the sky, paratroopers dropping into the stadium, and the Corps of Cadets and Brigade of Midshipmen marching onto the field.

More: Army-Navy: America's Game celebrates 120th meeting

The pageantry includes a "prisoner exchange," which allows the handful of cadets and midshipmen studying that semester at the other school, to finally "return home."

And this year, each team is wearing special uniforms: The Army will honor the hard-fighting, dog-faced soldiers of the 3rd Infantry Division, and the Navy will recognize the Silent Service, the stealthy and lethal submarine force.

No doubt, there also will be celebrities and top armed forces brass in the stands, perhaps even the secretary of defense, a West Point grad, and maybe — if the teams are lucky — the nation’s commander in chief.

President Joe Biden has attended the game as vice president.

Ten sitting presidents have watched the teams battle for bragging rights. The first was Teddy Roosevelt in 1901 and again in 1905. Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, Gerald Ford, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama each went once. George W. Bush and Donald Trump each went three times.

And Harry Truman — who wanted to attend West Point but was rejected and instead enlisted, fought in World War I, and earned a commission as a field artillery officer — went to the game every year while president except for one.

A representation of America

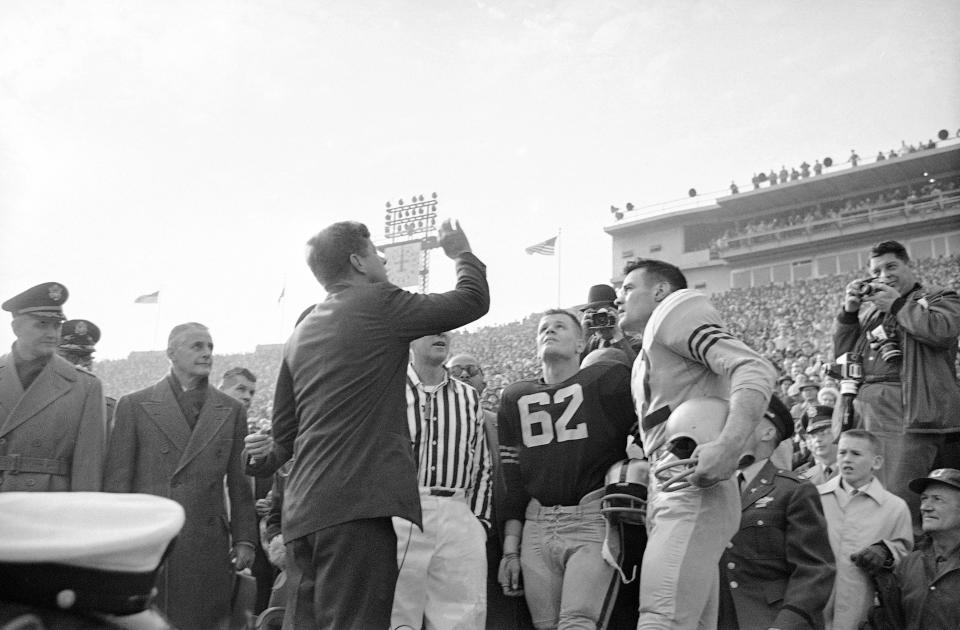

The president most associated with the Army-Navy game is John Kennedy. He was a Boston-area native, a Harvard man and a Naval officer. Kennedy loved the game and the service academies.

As president, he attended two games — sitting half the game on one team’s side, half on the other — and was set to be at a third before he was killed.

In a visit to West Point, he reminded the cadets that two of their graduates had become president. In one address at Annapolis, he said that he thought one of the most worthwhile things someone could do in life was serve in the Navy.

In another visit to the Naval Academy, he told the midshipmen: "In serving the American people, you represent the American people and the best of the ideals of this free society." To many, he added, you will be "the only evidence they will ever see as to whether America is truly dedicated to the cause of justice and freedom."

The Army-Navy matchup was so closely associated with Kennedy that after he was assassinated, the game was postponed. There was even talk of cancelling it, until Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline, insisted it still be played.

As for this year’s game — and Army’s not-so-secret psyops — it only seems fair to let a Navy fan weigh in.

"It’s a good game every year," said Rick Dupon, 54, of Houghton Lake, whose son is a midshipman. It was a diplomatic response. He is, afterall, president of Michigan’s Naval Academy Parents Club and has to set a good example.

But pressed for a response to Army's boasts, he didn't hold back.

"Go Navy, beat Army!" he added. "Navy is going to win. That’s all I’m going to say."

Contact Frank Witsil: 313-222-5022 or fwitsil@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Little, green Army men to lead the way to the Army-Navy game in Boston