Art Beat: Powerful projects in pursuit of food justice at Fuller Craft Museum

What are the causes of food injustice? There are many answers but consider the following contributing factors.

The average grocery store stocks a staggering 47,000 products, which implies that a multitude of options are available but the reality is that only a small number of corporations, including Monsanto, Tyson and Perdue are providing the product.

70% of all processed foods contain GMOs (Genetically Modified Organisms).

Meatpacking and processing is one of the most dangerous jobs in the US and much of it is done by illegal immigrants working at low wages.

The four top beef packers control 80% of the market.

McDonald’s is the single largest purchaser of ground beef, potatoes, tomatoes, pork and apples in the country.

Candy, potato chips and soda are less expensive than fresh produce.

The largest predictor of obesity is income level.

In 2017, 19 million Americans lived in food deserts, low income areas more than a mile from a supermarket in urban or suburban areas, or more than ten miles from a supermarket in a rural area.

What does all of this have to do with art? Fifteen artists are currently exhibiting at the Fuller Craft Museum in “Food Justice: Growing a Healthier Community through Art,” a powerful and disturbing show, organized by Contemporary Craft in Pittsburgh and which traveled to both Portsmouth and Columbus, Ohio before arriving in Brockton. The final stop will be in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

Stefanie Herr, a German-born artist based in Barcelona, Spain, displays a series of photographic relief sculptures that play to the disconnect between consumers and the meat that they enjoy, many never having seen a cow, lamb or pig in the real world. But, as she notes, they are “perfectly familiar with fingers, patties, meatballs or even Mickey Mouse shaped minced meat.”

Her three-dimensional images of some slain unidentifiable animal with a bulging eye in a faux styrofoam container or of a halved unskinned rabbit below a bundle of carrots serve to shock the viewer in a lowkey way, and yet remain both intriguing and enchanting.

Logan Woodle exhibits a trio of small pewter sculptures. “Clabber Ladle” is an udder-shaped scoop and he references his father’s understandable reluctance to throw things away, noting “he would just push it to the back of the fridge and wait…until it solidified. There’s nothing quite like the smell of month-old milk to get you going in the morning.”

Woodle’s “The House Built on Chicken Legs,” a shack with a chimney and porch astride a massive singular bird leg, suggests some at least minor economic success as it is accompanied by this statement: “We all leverage what we had to get started. Some started with more, some started with chickens.”

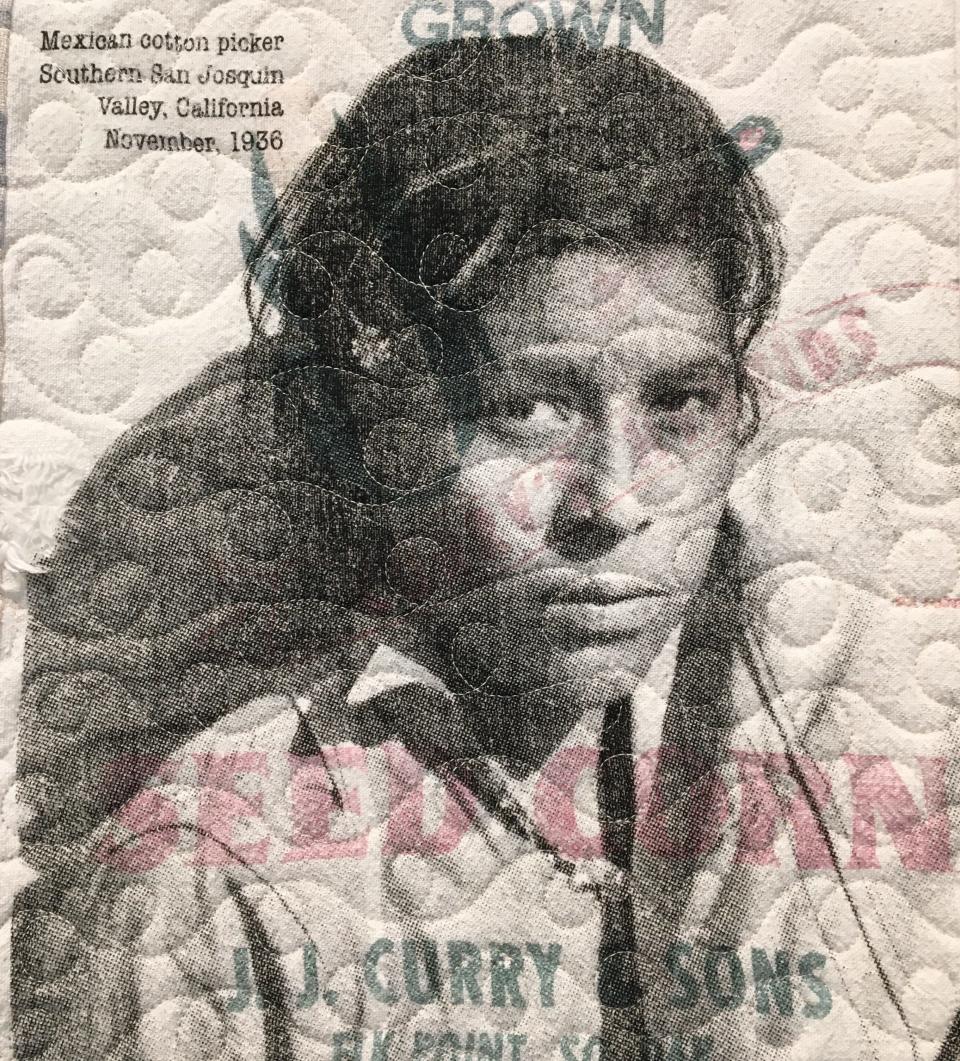

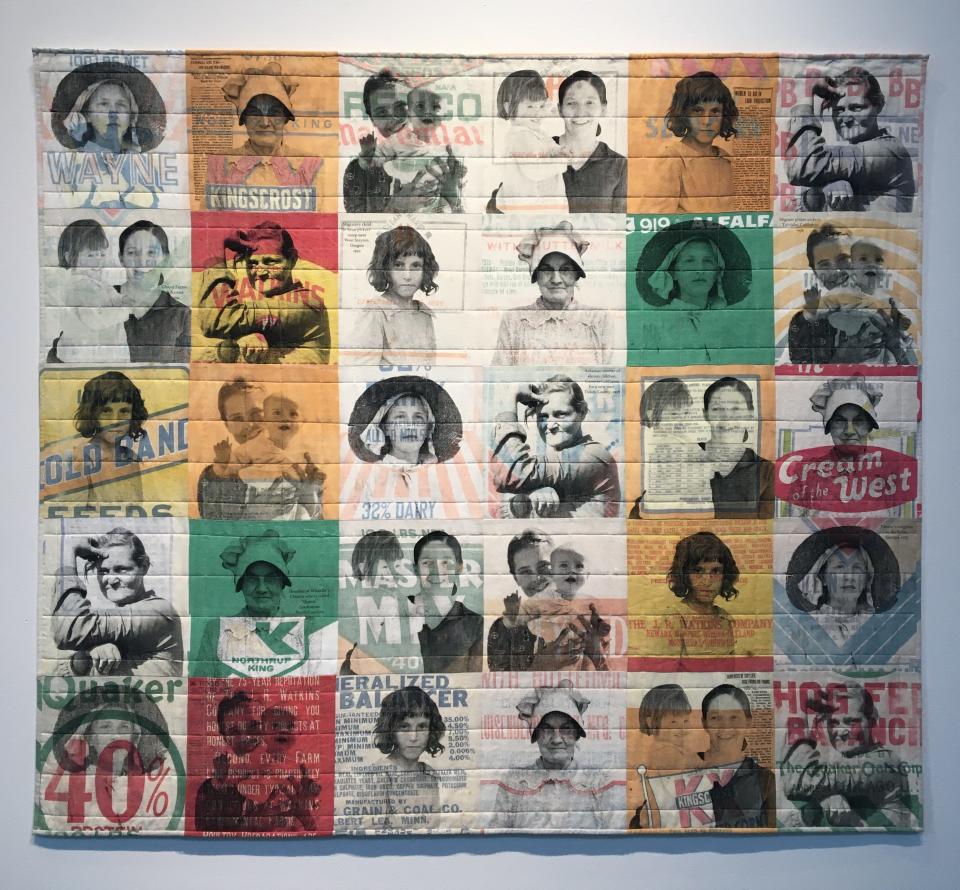

Patty Kennedy-Zafred’s hand-pulled silkscreened quilts are a heartfelt testament to the farmers of the past, utilizing photographs taken for the U.S. Farm Security Administration in the 1930s and ’40s.. On her “American Portraits: Deep Roots,” text identifies individuals such as “Mr. LeRoy Dunn, Negro tenant farmer, White Plans, Greene County, Georgia, June, 1941” and the unnamed “Mexican cotton picker, Southern Josquin Valley, California, November, 1936.”

The portraits of the people on “Deep Roots” and on a companion work “Heart of the Home,” mostly women and children, are as surely dignified, engaging and beautiful as any self-important celebrity on the cover of Vanity Fair or Rolling Stone.

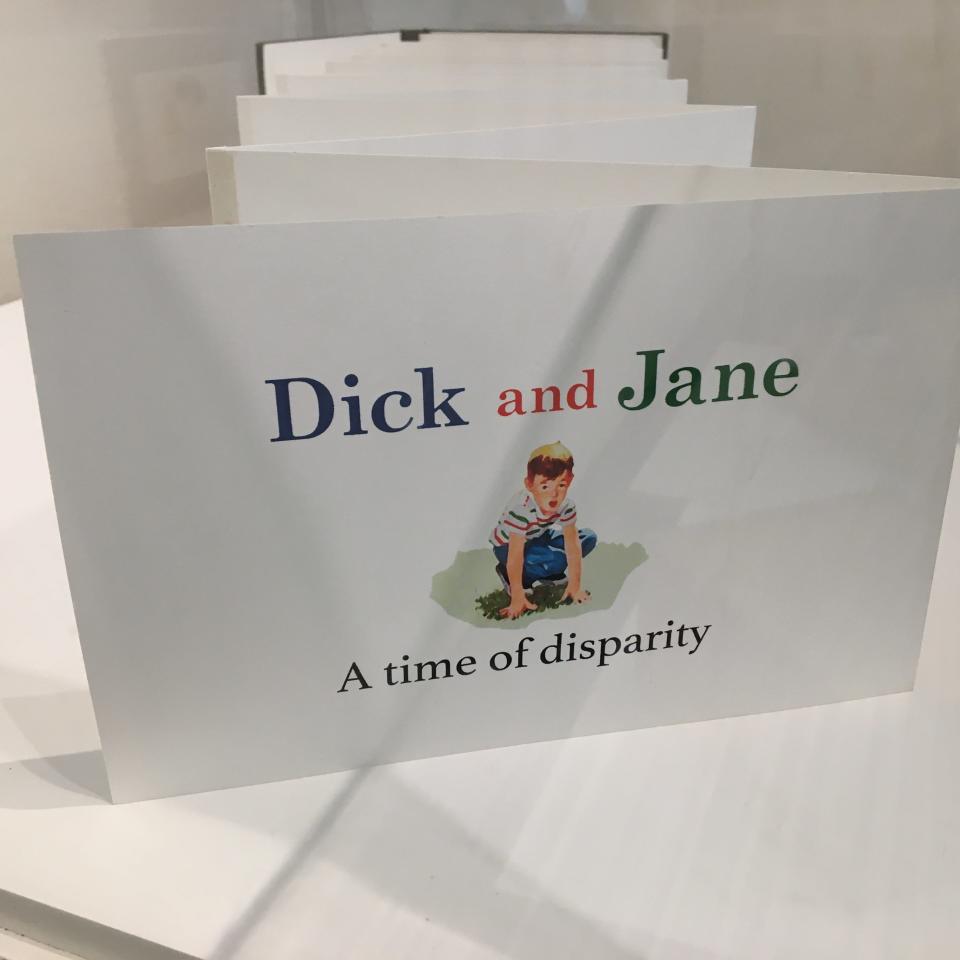

Joan Iversen Goswell’s accordion book, “Dick and Jane: A Time of Disparity,” is an indictment of food insecurity by virtue of the title alone: even the siblings of our collective childhood memories are hungry.

The most heartbreaking work in the exhibition is a multimedia installation that takes up an entire room. Created by Xena Ni and Mollie Ruskin, hundreds of receipts from Washington, DC supermarkets are suspended from the ceiling. A sign reads “I would have days where I didn’t get enough to eat.”

Every single receipt was given to a SNAP recipient with a message on it, a message which gives the work its title: “Transaction Denied.”

Enough said.

“Food Justice: Growing a Healthier Community through Art” is on display at the Fuller Art Museum, 455 Oak St., Brockton, until April 23.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Art Beat visits "Food Justice" exhibit at Fuller Craft Museum Brockton