How artist Mike Sleadd inked a legacy at Columbia College and beyond

Settling into any community means watching how some things change and some things stay the same. This universal truth comes into more specific relief when a community rests upon creative cornerstones the way Columbia does.

To wit, a creative cornerstone like Mike Sleadd.

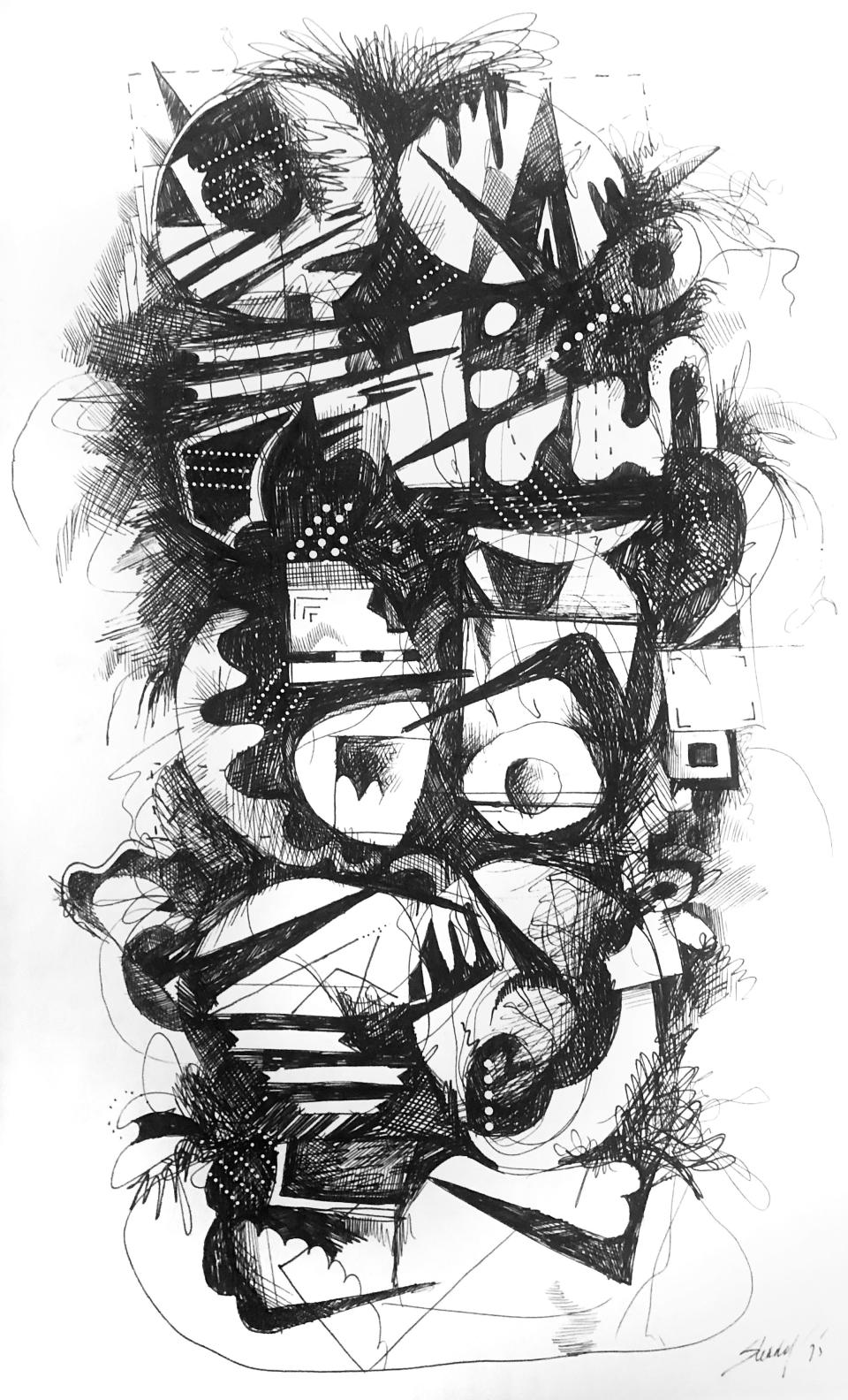

Among Columbia's most beloved artists, known for a pen-and-ink style that's unmistakably his, Sleadd recently enjoyed a long-awaited graduation alongside his students at Columbia College. After 35 years, he is retiring from the classroom, remaining on campus for another year to inaugurate an artist-in-residence program.

But as he keeps working, keeps applying his imagination with pen and feather, Sleadd — the sort of artist for whom the phrase "to wit" was invented, the sort of artist the phrase cannot contain — will keep teaching us the way he always has.

Sleadd's work guides our gaze, to see the world just a few degrees askew and, in doing so, notice the abundance in and around us.

More: From Peach Pit to Guster, 5 can't-miss Rose Park shows this summer

A portrait in permanent ink

As this extensive chapter closes, the soul of Sleadd's art is visible in a joint exhibit with woodworker Tom Stauder at Orr Street Studios. To receive all his drawings stretch out to offer, viewers should approach them with a few principles in mind:

Take the craft, but not yourself, serious.

Look between — and around, and directly at — the lines.

Be willing to find the beautiful in the bizarre, the bizarre in the beautiful and yourself somewhere among it all.

That is, approach the work as Sleadd does.

"It's play. But it's a very serious play," he said in a recent interview. "Take what you do seriously, but not so seriously that you don't have fun doing it."

Sleadd swears his style — and viewers' reactions — have remained consistent since his arrival in Columbia to attend graduate school at the University of Missouri. Sleadd's beholders remark at being drawn into the weirdness of a piece, of truly liking that weirdness, he said. They regularly puzzle over both small details and the greater tone, he added. Is the work meant to be funny or not?

Viewers will compliment the work, but they don't necessarily want it hanging over their couches, Sleadd joked.

Certainly, his affection for material and medium is unwavering. A Sleadd original often begins with "expressive gestures using the ink-soaked plume of a feather," his website notes. "From those initial strokes, he weaves an array of patterns into detailed, whimsical abstractions."

"I like ink because it's kind of unforgiving. You put the line down — you've gotta live with it. You've gotta make it work, make it part of the composition," Sleadd told the Tribune a decade ago. "... I've said it before, it's kind of like life to me: If you make a mistake or you put things into your life, you've got to learn to live with them and incorporate them into who you are and what you do. I like pen and ink for that reason."

Sleadd's particular aesthetic developed in response to a rudiment of the drawing life. He enjoyed capturing the figure, but "I always wanted more there," he said this spring.

Getting beneath the skin of a person or story, he brings the stuff of life to the surface. Some of Sleadd's details are actual, some fantastical; but like a poet who uses license to inch closer to real, messy humanity, he shows us who we are through invention.

And Sleadd shows us who he is. Some work more bears a more literal resemblance, incorporating a version of his visage. But all Sleadd's drawings reflect something about the man himself.

"Mike's drawings, in particular, seem very personal to me," his friend and collaborator Chris Teeter once told the Tribune.

In Sleadd's presence, as in his art, distinct personality reveals itself in small, sensory details: a shock of hair nearly as white as the paper he creates on; a lingering hint of his Old Kentucky Home to his timbre; a warm, unforced laugh.

Kindness and curiosity uphold every conversation, just as they exist somewhere in or around every drawing. And joy suffuses the process. When a piece satisfies Sleadd, a grateful feeling attends.

Sometimes the feeling washes over him well before a piece is done; sometimes it inspires a spontaneous dance around the room, he admitted.

Connected to Columbia

Sleadd speaks with generosity, and the first lines of inside jokes when discussing the collaborators and classrooms comprising his time in Columbia.

As a graduate student, the very shadow of iconic artist Frank Stack influenced something as fundamental as Sleadd's line work. Attentive teachers like Brooke Cameron cultivated his printmaking skills; Sleadd would go on to teach alongside her husband, the late Ben Cameron, for years.

More: What to know about Memorial Day fave Pedaler's Jamboree, a bicycle and music fest

Friends like Teeter, well-practiced in assemblage sculpture, helped Sleadd understand his own work — which he views like an assemblage of line, texture and other elemental realities, he said. And an ongoing collaboration creating book covers for Missouri's first poet laureate, Walter Bargen, offers Sleadd one more avenue to come alive.

People have made Columbia the right home for his work all these years, he testified.

"There are a lot of really great people who happen to be artists — or artists who happen to be great people," he said.

And it's the people he will miss as his teaching tenure ends. A few years in the making, Sleadd's decision allows him to join his wife, former Columbia City Councilperson Barbara Hoppe, in retirement and cede his position to a younger teacher.

The best parts of teaching came from conversations, "being immersed in talking about art ... talking with young people," Sleadd said. He will miss his students and fellow faculty — many of whom he helped hire, he said — but keeping a studio on campus for the next year will allow him to enjoy Columbia College's culture without teaching's demands.

A 'visible man'

Facing the prospect of as much or little studio time as he wants, Sleadd will encounter artistic questions universal and personal. Like any creator, he's always refining the balance between control and reflex in his work.

Dealing now with arthritis, Sleadd knows he also needs to see what his veteran hand can do, to keep negotiating the relationship between his will and his body's.

And though his style remains steady, Sleadd remains open to fresh expressions of what's innate. A few years ago, an anonymous someone left a bag filled with driftwood at his door — Sleadd has at least one solid suspicion about who.

Keeping the scraps with no real reason in mind, he eventually arranged the wood against the solid black of a desktop. He began to see shapes that looked like his. Always seeking the elusive more, he sanded the wood, went back into arrangements and drew in elements before sealing a composition with a photograph.

Years ago, Sleadd's hand-penned a different sort of art, a painfully exquisite poem called "Visible Man." Small details loom large, as he again brokers unity between sincerity and strangeness; he conjures both Bing Crosby Christmas songs and "the stink of urine" saturating a hospital.

The poem's speaker feels overcome by their father's illness, emotionally and literally as a gurney runs across his toes. The growing thinness of his father's skin calls to mind a Visible Man toy which allowed his childhood self to view the bones and body parts that really make up a human being.

Amid the bleak present and these memories, Sleadd writes a passage as honest and rich as anything he's ever done:

I've seen the truth.

Everything that we've ever seen, everything that we've ever thought, everything that we've ever heard is collected inside of our bodies. Miraculously.

This is why we hurt.

A sort of modern proverb, these words come close to encapsulating the brilliance of Sleadd's artwork and his intentions. The abundance of who we are miraculously collected inside a picture plane, showing us at least a little of what's beneath the artist's skin.

Sleadd has been Columbia's visible man and will continue to be so in contexts that are different yet the same.

A-May-Zing: Art by Mike Sleadd and Tom Stauder is currently on display at Orr Street Studios. Visit https://www.orrstreetstudios.com/ for hours and more information.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: How artist Mike Sleadd inked a legacy at Columbia College and beyond