How Artists Are Using Their Work As a Protest Tool

The spring of 2020 in the United States will certainly be remembered as one of the most pivotal times in the country’s history. The brutal and senseless murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others have inspired impassioned protests around the world for equal rights and protection for Black Americans. And, in this age of social media dominance, art inspired by both the victims and the protests has been an effective way to convey the urgency of the situation.

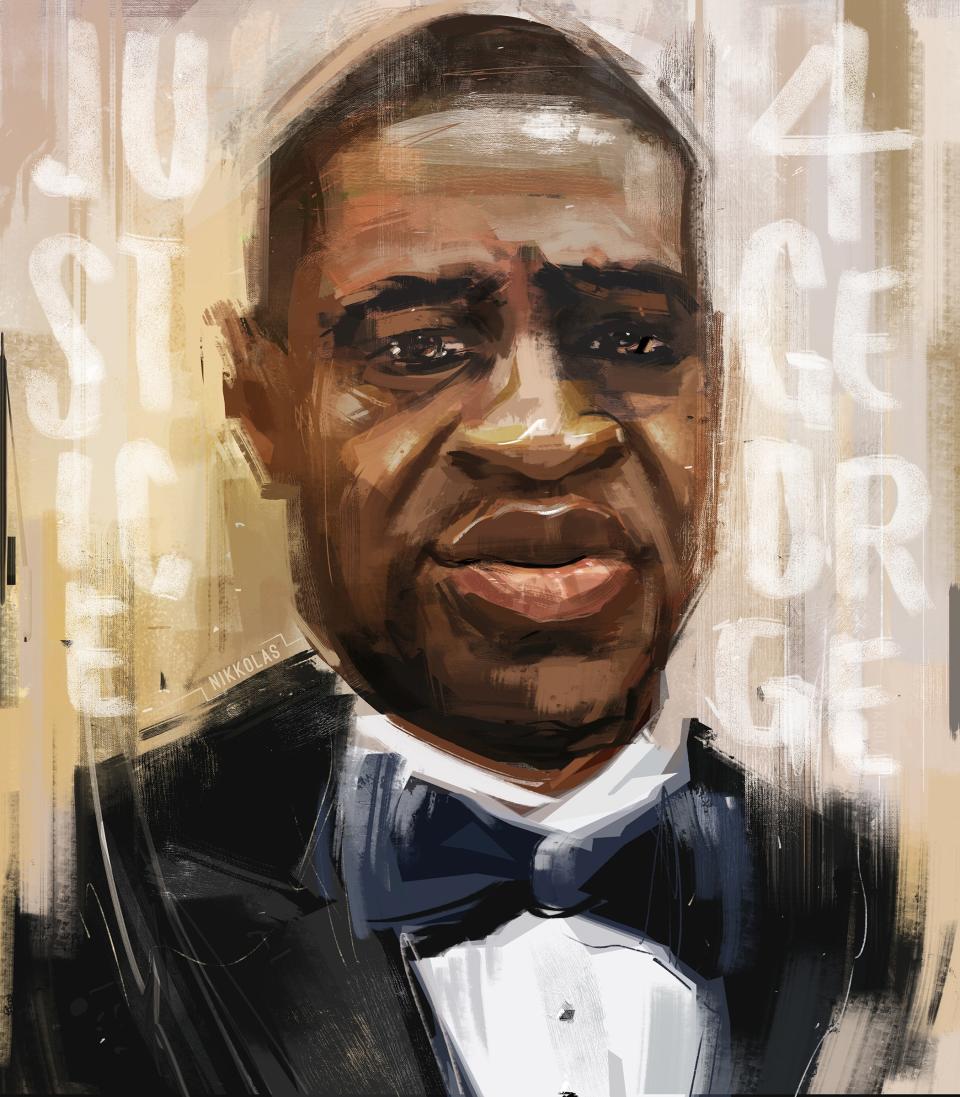

The most arresting pieces do what words cannot: They give viewers a tangible image of the victim or devastation, which can then be shared with one click. Nikkolas Smith’s painting of George Floyd quickly spread across Instagram after he posted it in late May. The portrait, with Floyd in a tuxedo, features the words “Justice 4 George” in white letters written on either side of his face. “I found an image of George Floyd in a black hoodie, and thought that was a good base reference to begin with, but in my re-creation tribute, I wanted to suit him up with a tuxedo, and focus his eyes directly at the viewer,” Smith tells Architectural Digest. The artist added in the post’s caption: “George Floyd’s life mattered…Black lives in this country are being destroyed by a virus of racism, fear, and hatred. It is up to everyone to take a stand and actively work to tear down this centuries-old pandemic. NOW.”

Smith, who describes himself as a concept artist, author, and illustrator, has also created portraits of other victims of police brutality like Breonna Taylor, as well as sketches such as a protestor kneeling with a mirror in front of a line of armed police. “I’m so grateful to see that the art is being displayed through social media all over the world, and I’ve even seen it show up on protestors’ signs in various places,” he says. “If it is displayed in this way alone, I would be overjoyed that it has achieved its purpose.”

Other artists are using more immersive tactics. Jammie Holmes flew banners with the last words of George Floyd over five major U.S. cities, forcing everyone there to look up and take notice. Over New York, most chillingly, flew “THEY’RE GOING TO KILL ME.” Holmes explained his intent in an artist’s statement on his website: “This presentation is an act of social conscience and protest meant to bring people together in their shared incense at the inhumane treatment of American citizens,” he wrote. “The deployment of Floyd’s last words…underlines a need for unity and the conviction that what happened to George Floyd is happening all over America. An enduring culture of fear and hateful discrimination has only increased in its intensity since 2018, and a critical mass will no longer allow it to be ignored.”

And while Holmes is “charged” by the response to his work, “the emotions surrounding it are complicated,” he tells Architectural Digest. “It’s amazing to see the positive action from across the country supporting the Black Lives Matter Movement and the pursuit of truth for so many who have been hurt and killed by racial injustice. I’m hopeful for real change but saddened that all this was necessary to even begin to consider our basic rights.”

Hank Willis Thomas is another artist who is using words as a primary medium. Last month, Thomas and his collaborator Baz Dreisinger projected writings from prisoners fearful of catching coronavirus while in jail onto Manhattan criminal justice buildings. Sentences such as “As the death toll began to grow, fears of losing loved ones grew too,” were displayed in bright green across the buildings. People of color are disproportionately affected by America’s criminal justice system, and prisoners, in tight jail quarters, are especially vulnerable to the dangers of COVID-19. The installation, called The Writing on the Wall, is an updated version of a project that the pair mounted on the High Line in New York City last year; they plan to display it in other cities around the globe. Thomas has also been posting some of his other salient works on his Instagram, including a 2014 image called Two Little Prisoners, which features two young Black boys standing next to the white cop who arrested them during the 1965 Watts riots.

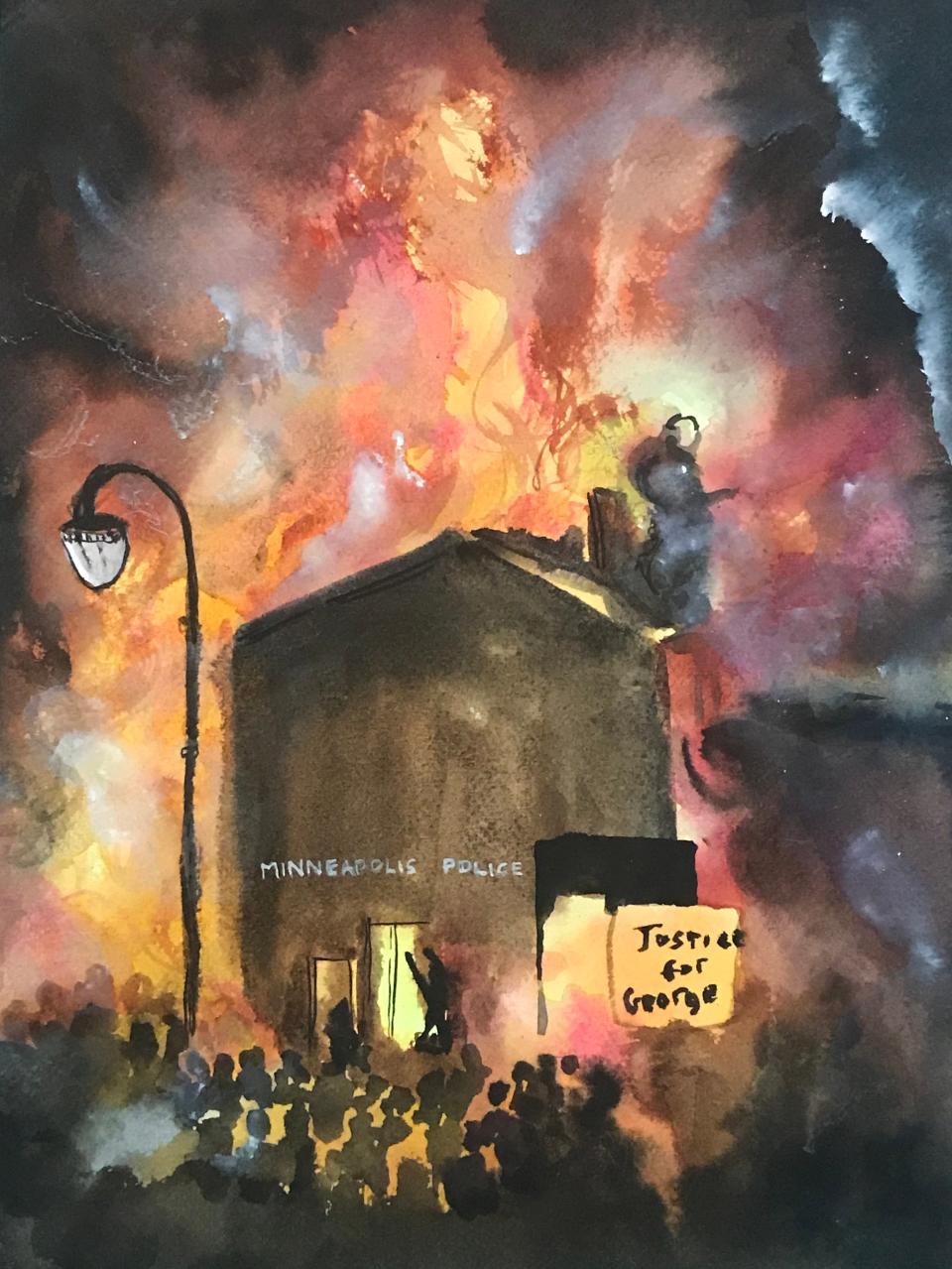

Artists are also sharing others’ work to amplify their effect. Willis Thomas posted visual artist Kambui Olujimi’s arresting ink on paper of a burning Third Precinct in Minneapolis, where “Justice for George” is written in the lower right-hand corner. “Artists are a conduit to a communication that operates outside of language,” Olujimi tells AD. “Art offers a space of simultaneity and complexity that many types of rhetoric do not. We have the opportunity to make historic documents that are extremely personal, critical, and transcendent.”

And indeed, long after this wave of protests has finished, the paintings, sculptures, and installations that were created or revived during this period will be an indelible reminder of this moment in history. We can only hope they also help to enact enduring change as well.

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest