Ashland Memories: Farming and a diverse local economy

We tend to think of Ashland in the early days as a farming community, but farming supported a diverse economy.

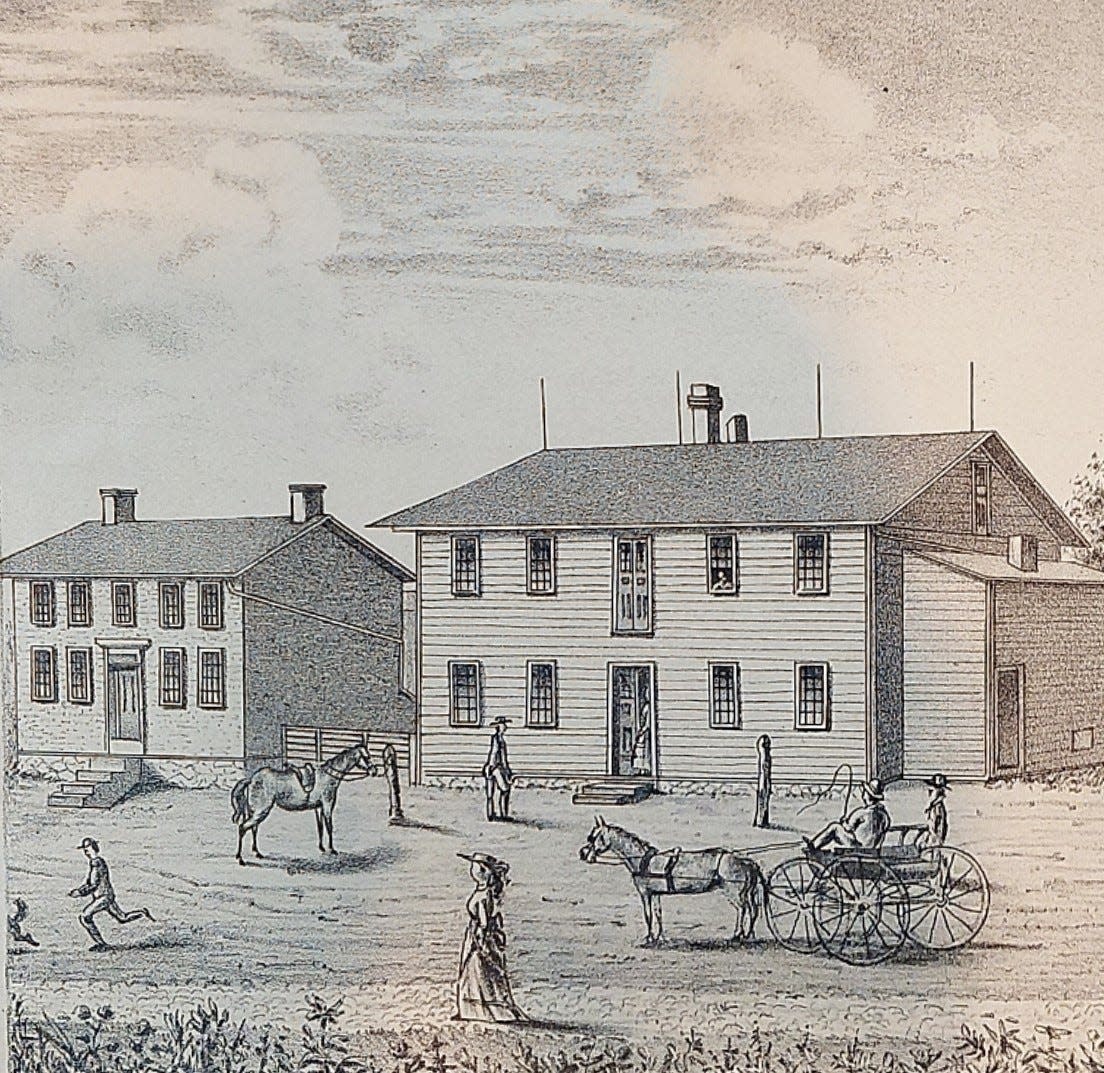

We might now say of a local village “don’t blink — you’ll miss it!” But every crossroad was once a thriving center of commerce, boasting of small-scale industries, merchants, and professional services.

Writing in the midst of the Civil War, historian H.S. Knapp enumerated the population and listed the businesses and social institutions of the various villages and townships in the county.

I will give Hayesville as a representative sample, but every village had a similar description. With a population of 336, Hayesville contained three churches, two doctors, one lawyer, and a barber. There were five boarding houses and one high school.

Residents could shop at three dry goods stores, two clothing stores, two boot and shoe stores, and one drugstore.

Hayesville was producing as well as selling. The village had a bakery, two shoe makers, three saddlers, and three wagon makers. Local artisans included four blacksmiths, a silversmith, a tinsmith, two coopers, three cabinet shops, and two tanneries.

The villages scattered throughout the county ranged in size from Perrysburg (now known as Albion) with the smallest population of 115 residents, to Hayesville and Savannah with 336 each.

Population shifts when families move West

Although Mohicanville had a population of under 200, Knapp called it “a hive of industry and thrift.” He attributes this to its water power, which came from three springs that flowed from the top of the hill and fell 100 yards. This resource ran three water wheels, powering a grist mill, a sawmill, and a woolen factory.

In 1860, the population of the entire county was roughly 20,689, while the village of Ashland, which had been the county seat for just 12 years, had 1,748 residents.

Despite his descriptions of the flourishing village economies, Knapp noted that the population in some of the townships had decreased over the last 12 years. Some families were selling out to move West, and their lands were being absorbed into larger farms.

Knapp lamented that “sections of land that formerly sustained six and eight families, are now occupied by one and two families”— a situation which he said had not increased the productivity of the county.

A letter written in 1887 showed that this trend accelerated following the Civil War. Before the war, the average farm was 40 to 160 acres. However, some 2,000 men, largely young and middle-aged, left the county between 1860 and 1870. The remaining landowners consolidated their holdings into larger farms.

The letter writer described the men who returned from the war as “worn out, broken down constitutionally.” They had made little money during the war, while high wartime prices had benefited those who stayed home. Veterans who could not afford local farms tended to move on. Many sought homesteads in the West.

This meant Ashland’s population decreased in the decade after 1860, and remained about level through 1880. As the children of the 1860s grew to adulthood, however, it was expected that population numbers would again rise.

This article originally appeared on Ashland Times Gazette: Ashland Memories: Farming and a diverse local economy