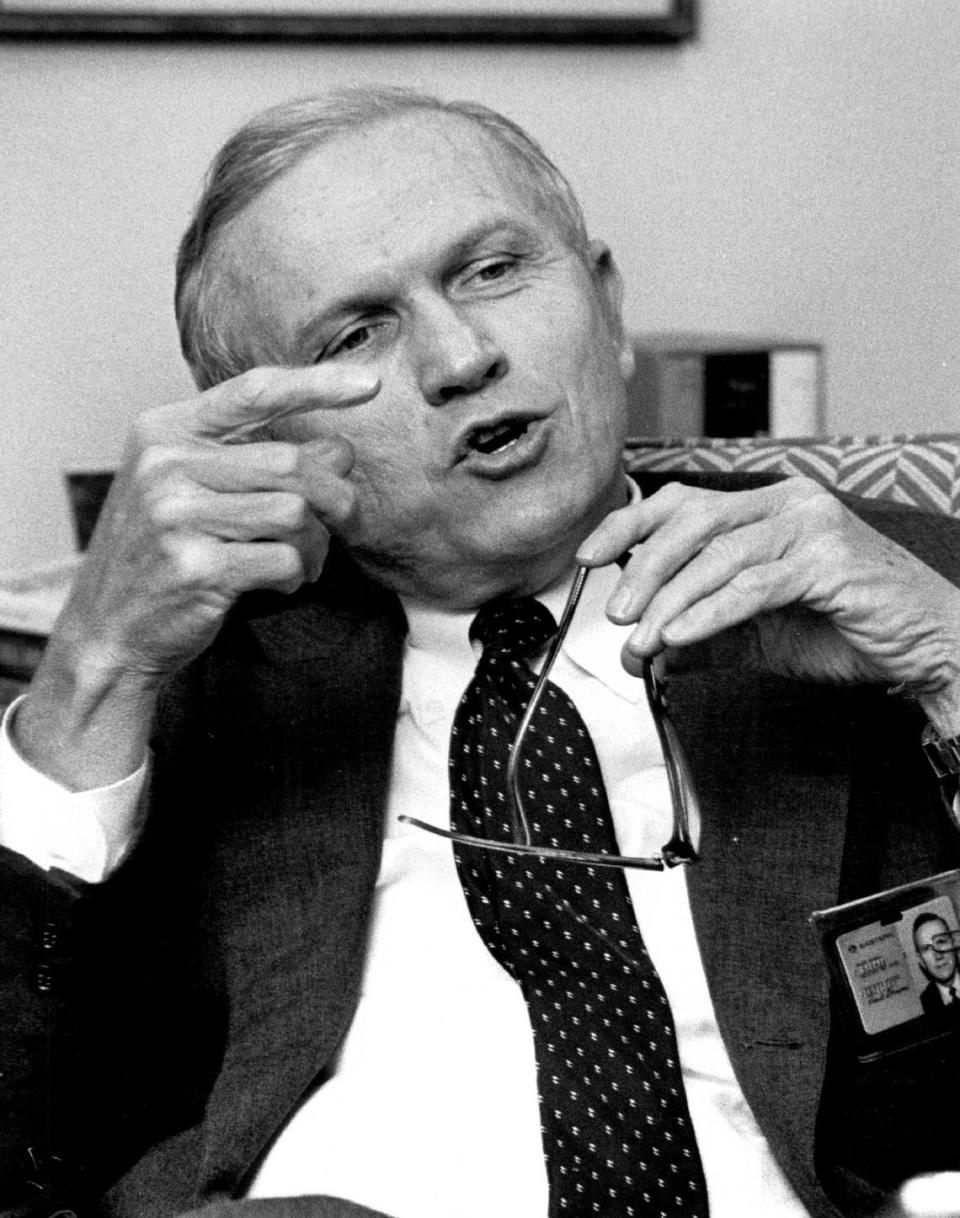

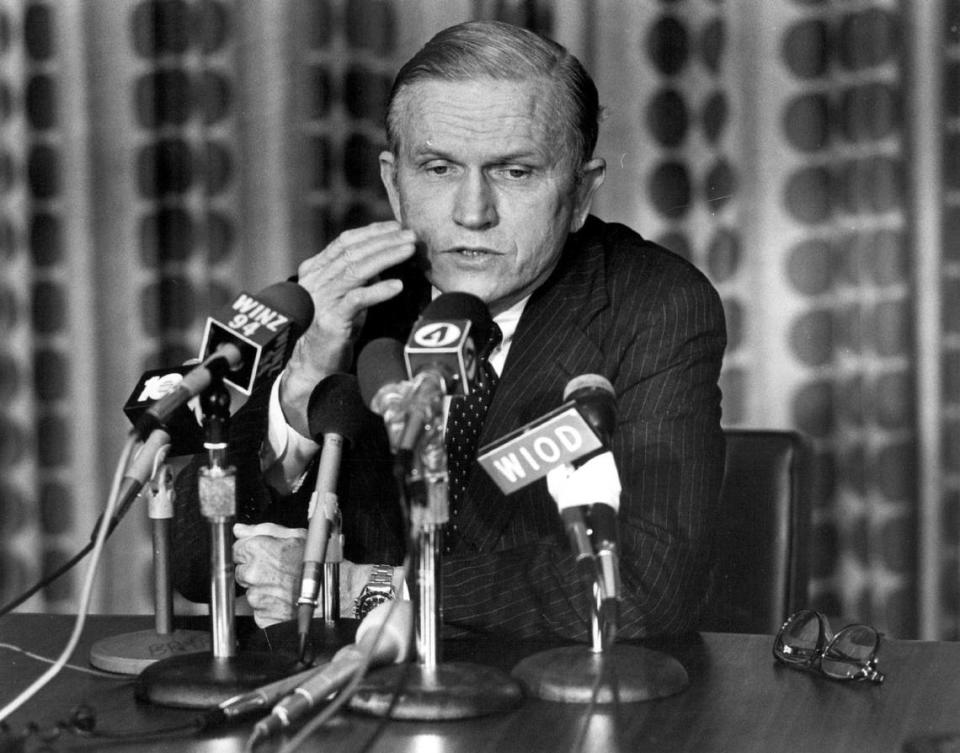

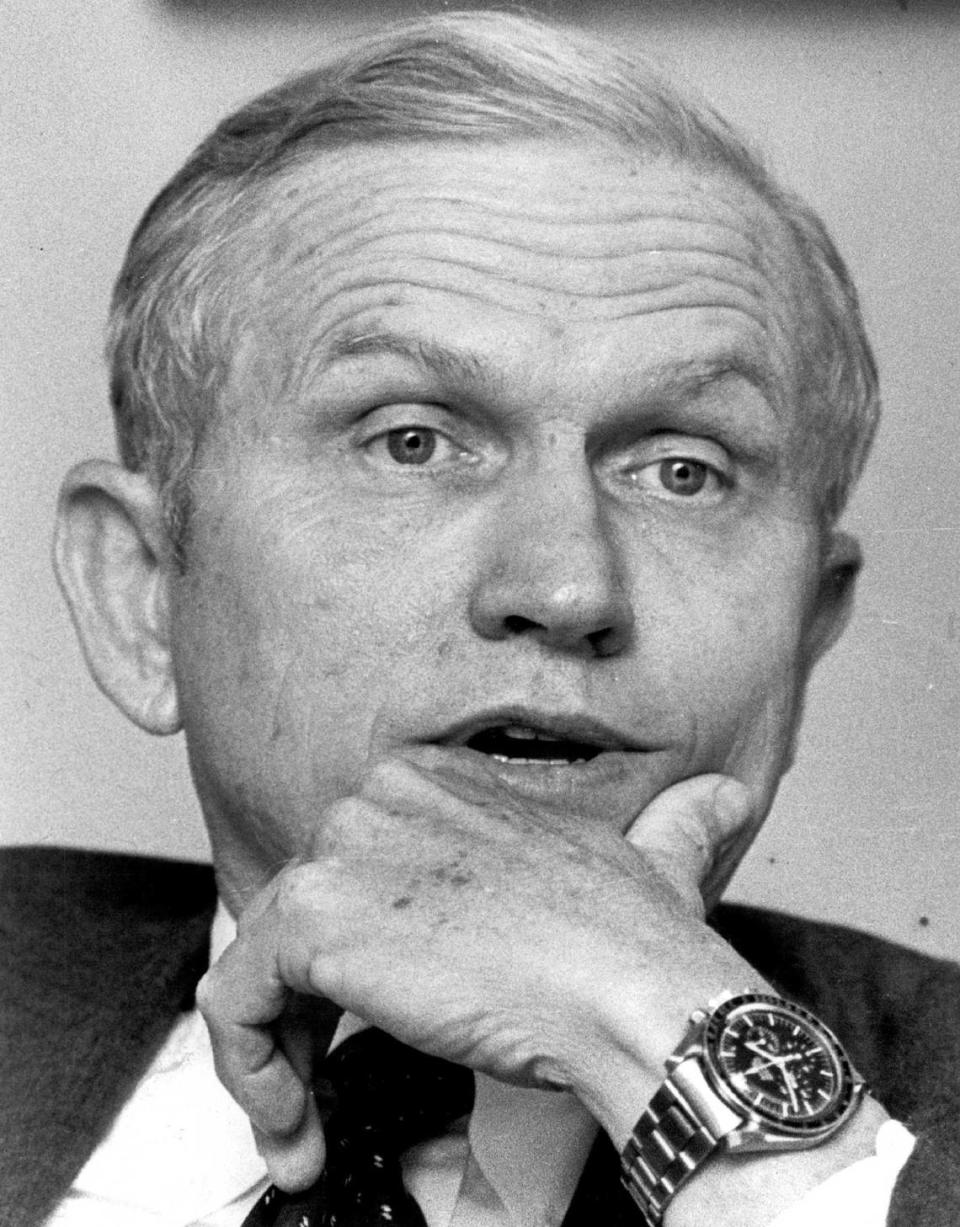

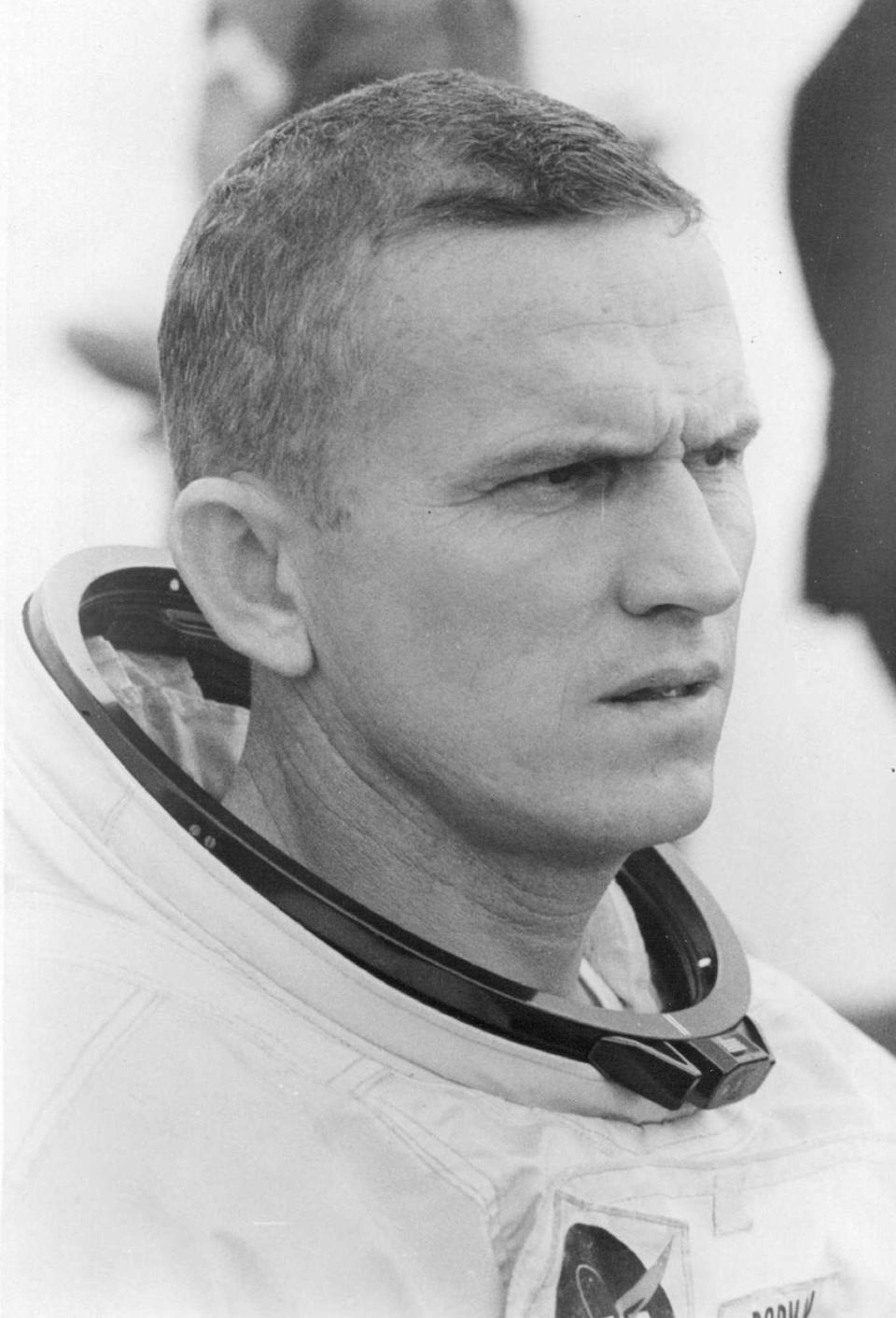

From astronaut to Eastern Airlines leader. How Frank Borman changed the world of flying

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Frank Borman, NASA astronaut and leader of Miami-based Eastern Airlines, has died at 95 in Montana.

In 1968, Borman was commander of Apollo 8, the first mission to orbit the moon. A decade later, he was leading Eastern, piloting the company through financial and labor troubles and starring on TV commercials telling viewers, “We have to earn our wings every day.” He resigned from Eastern in 1986 when the troubled airline was sold.

Here’s a look through the Miami Herald archives at Borman’s time at Eastern:

BORMAN SAYS GOODBYE TO MIAMI

Published July 3, 1986

Frank Borman, former Air Force pilot, astronaut and chairman of Eastern Airlines, said his final good-byes to Miami’s business community Wednesday, and went on record for the first time against casino gambling in Florida.

Borman also forecast more labor troubles for the Miami- based carrier, as Texas Air Corp., its prospective new parent, moves to reduce labor costs further.

Appearing with his wife, Susan, at a luncheon sponsored by the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce, Borman noted that he remained neutral on political issues during his 16 years at Eastern because of the competitive nature of the airline business.

Now that he’s resigned, Borman felt no such constraints.

“I feel very strongly that gambling would probably be the worst thing that could happen to Miami,” he told an audience of 185 businessmen. “I hope that your continued leadership would prevent that from happening.”

Later, Susan Borman, who along with her husband was hailed for supporting United Way and helping to fight drug abuse and crime in Dade County, was even more succinct.

“If you want to talk about a longterm cancer in a sick society, and if that’s the way you want the community to go forward . . . then you continue to bring in that element,” she told reporters.

Borman focused his other concerns on Eastern’s future and that of Miami International Airport.

He said Eastern’s labor costs are still too high despite 20 percent pay concessions by most of the company’s workers.

“That struggle will continue, hopefully on a rational basis, probably not,” he said, “because of the simple fact that the environment that we seem to deal in makes it very difficult for rational proposals.”

Borman added that it was a “major mistake” to discard a proposed site in the Everglades as a location for a new airport. He said Miami International on any busy day is overcrowded and “outmoded.”

Before Borman spoke, Alvah Chapman, chairman of Knight- Ridder Inc., Alexander McW. Wolfe, vice chairman of Southeast Bank, and David Blumberg, president of Planned Development Corp., heaped heavy praise on the Bormans for their contributions to Dade County.

Borman’s last day as Eastern’s chairman and chief executive was Monday. Although Texas Air has appointed him vice chairman of the Houston-based holding company, the Bormans will live in Las Cruces, N.M., to be with one of their sons while the former astronaut writes a book about Eastern.

As the leaders spoke of the Bormans’ deep religious commitment, integrity, and compassion toward others, cracks appeared in Borman’s businesslike, “right stuff” veneer. Occasionally, his eyes welled up, while at other times he flashed a broad smile and winked at his wife.

Asked later if he indeed was overwhelmed, Borman’s thrust his eyes toward the floor, replied “Yup,” and walked away.

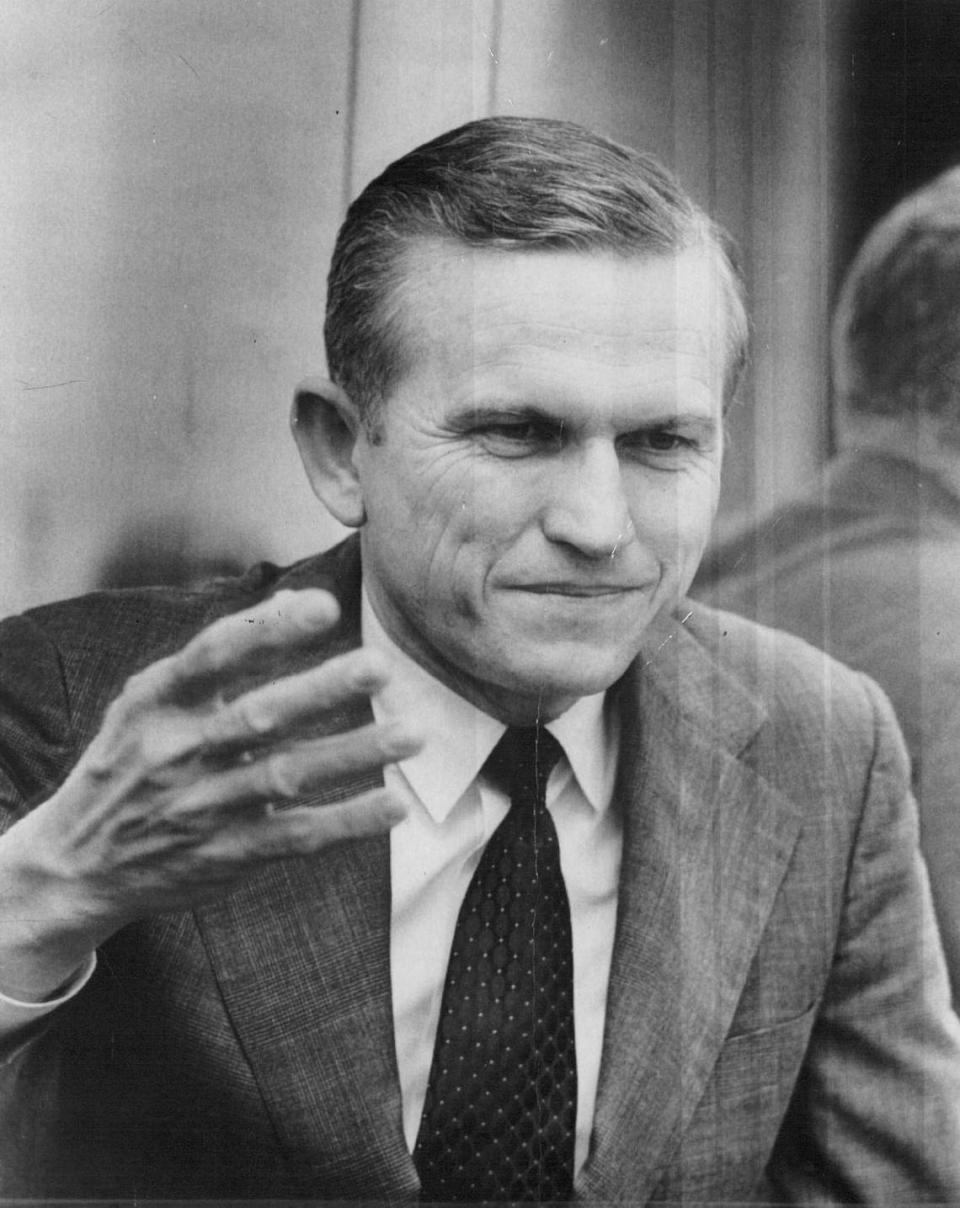

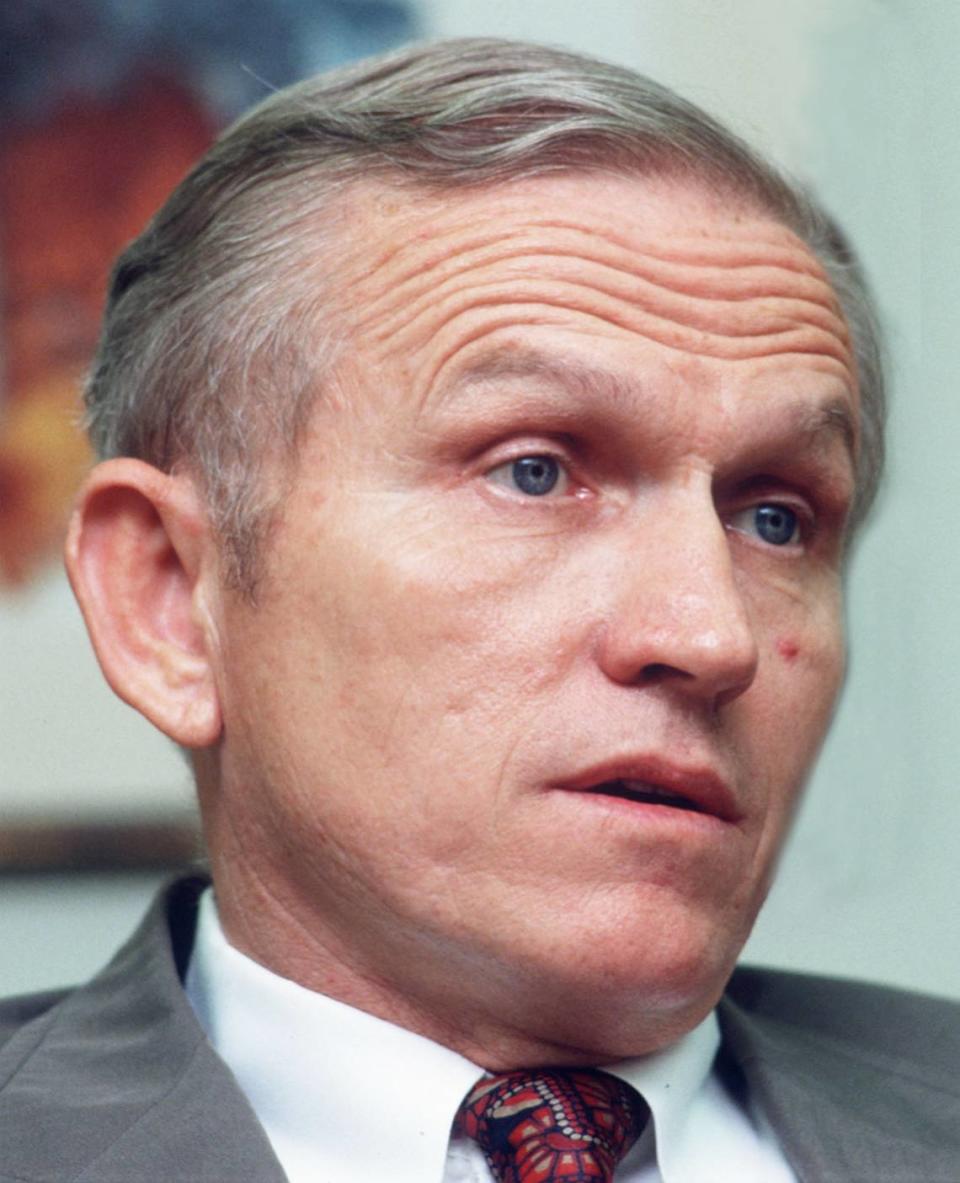

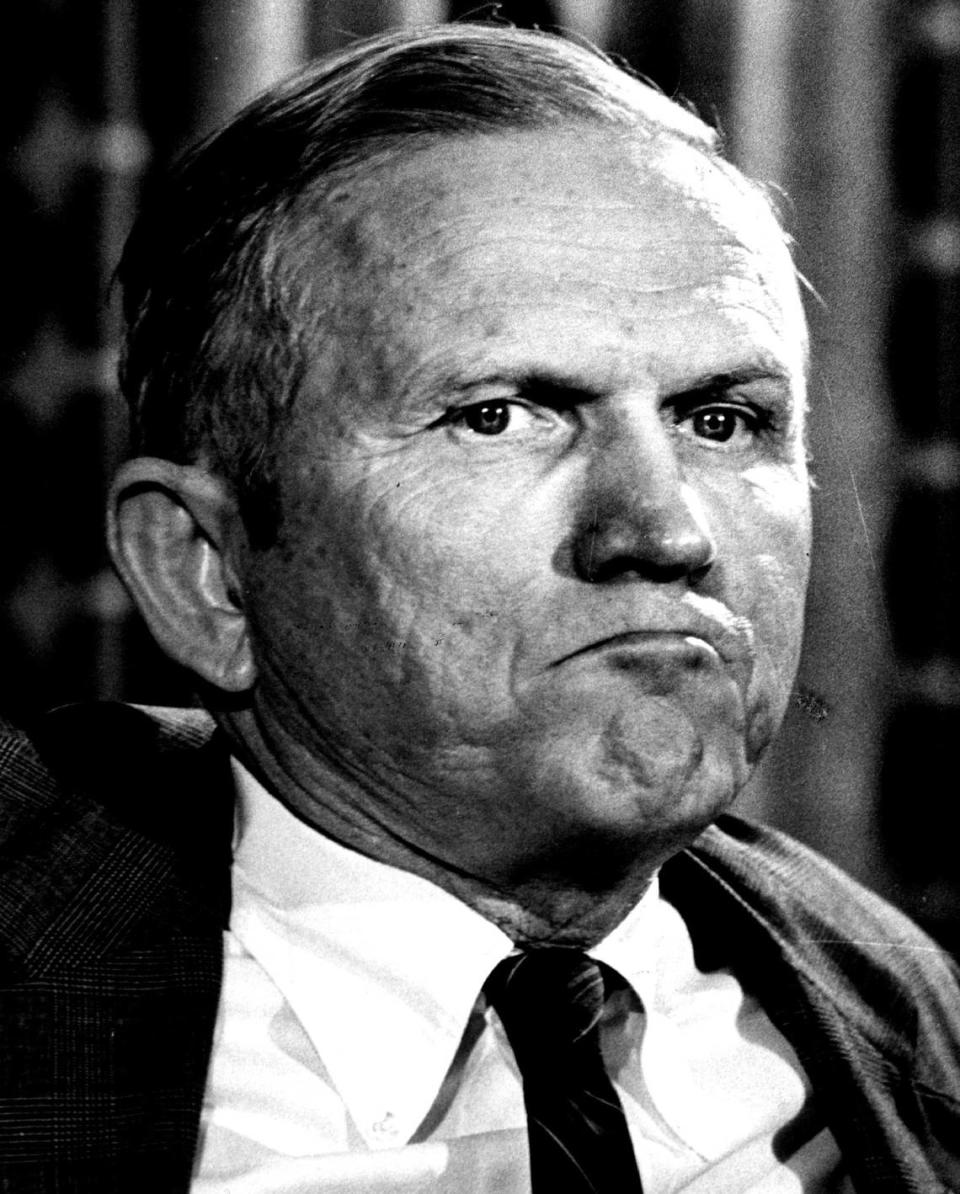

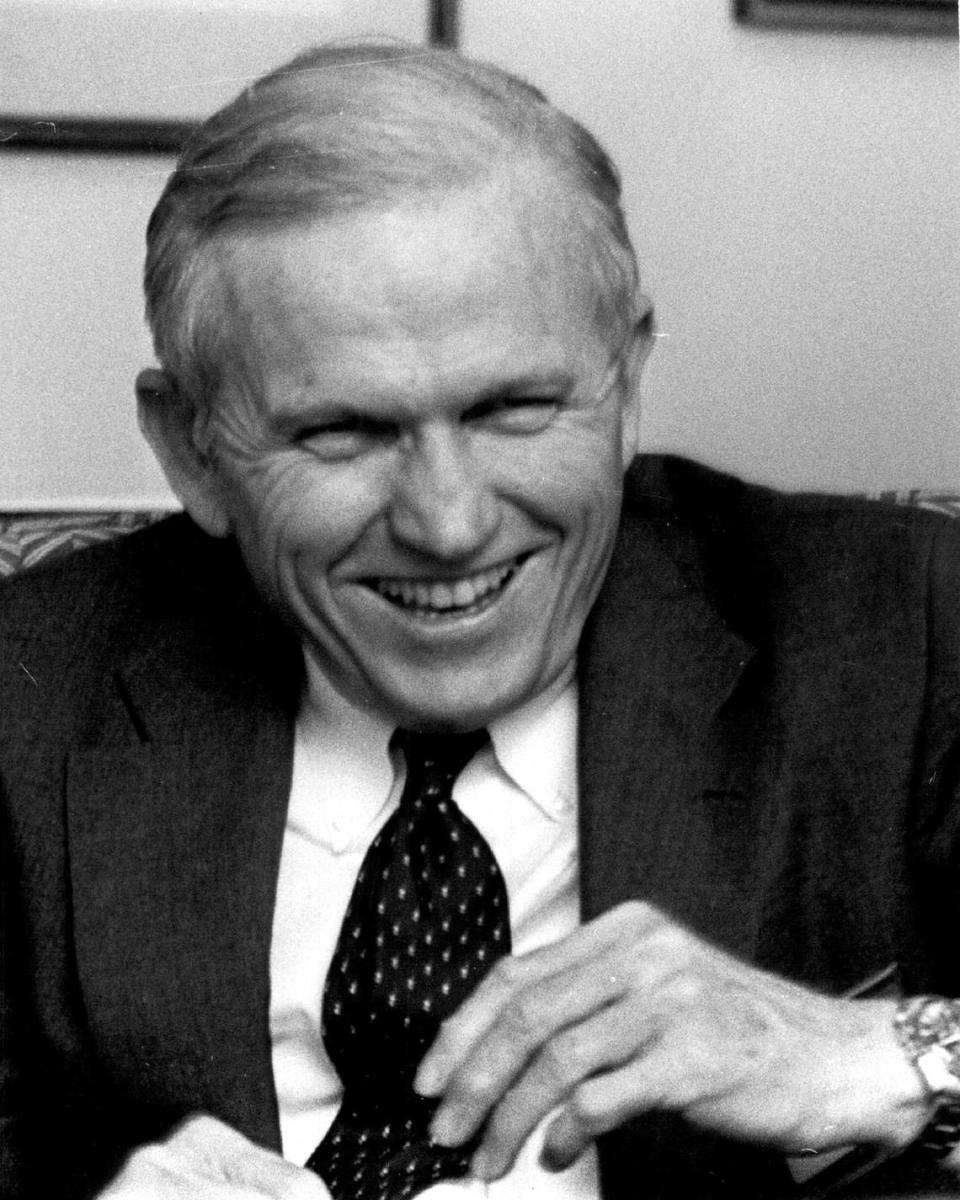

PHOTOS: THE MANY FACES OF FRANK BORMAN

BIOGRAPHY: FRANK BORMAN THROUGH THE YEARS

March 14, 1928: Born in Gary, Ind.

1943: Begins taking flying lessons, at age 15.

1950: Graduates with bachelor’s of science degree from U.S. Military Academy at West Point; eighth in class of 670.

July 20, 1950: Marries Susan Bugbee.

1950: Transfers to Air Force to take flight training at Williams Air Force Base in Arizona and earns wings the next year.

1951: Becomes a fighter pilot with 44th Fighter Bomber Squadron in Philippines.

1953: Returns to U.S. and becomes pilot and instructor at Air Force’s Fighter Weapons school.

1957: Graduates with master’s in aeronautical engineering from California Institute of Technology.

1957: Becomes assistant professor of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics, U.S. Military Academy.

1960: Becomes test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base in California and serves as instructor at Air Force Aerospace Research Pilots School.

1962: Becomes astronaut in second group of astronauts named.

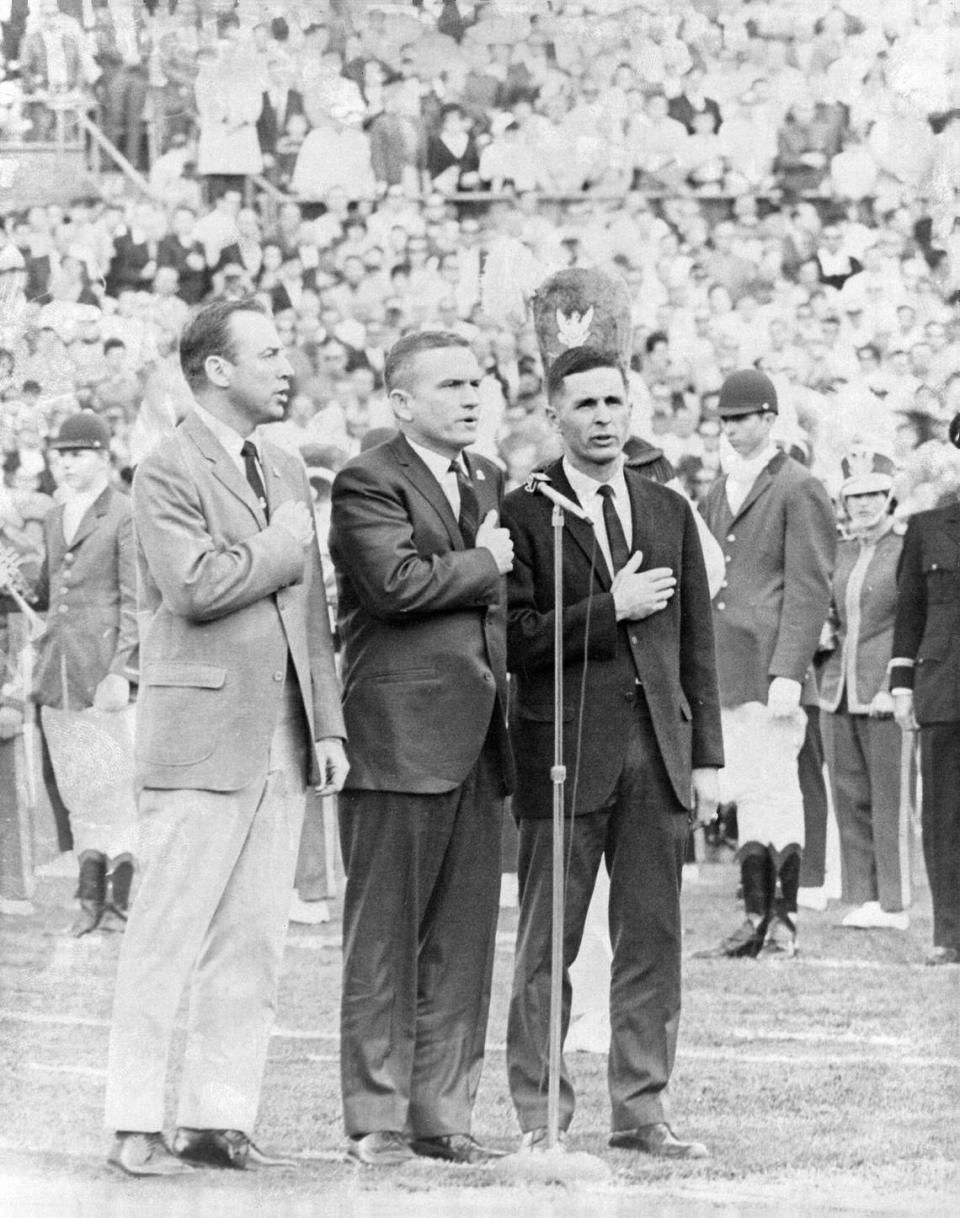

December 1965: Serves as command pilot on 14-day orbital Gemini 7 flight with James McDivitt that rendezvoused with Gemini 6 with Walter Schirra and Thomas Stafford.

January 1967: Joins board investigating fire that kills three Apollo astronauts in test module (Borman was the first person to enter the chamber after the fire); later heads engineering team making modifications to translunar vehicle recommended by review board.

December 21-27, 1968: Serves as command pilot for one-week Apollo 8 flight, first lunar orbital mission.

1969: Named deputy director of flight crew operations in Houston.

1969: Becomes special adviser to Eastern Airlines.

1970: Retires from Air Force as colonel.

June 1, 1970: Becomes Eastern senior vice president for operations.

1974: Named executive vice president and general operations manager.

May 27, 1975: Becomes president and chief operating officer.

1976: Named Eastern chairman.

1983: Buys Miami auto dealership with two sons, Fred and Edwin.

June 1, 1986: Announces resignation from Eastern.

HOW FRANK BORMAN TRIED TO SAVE EASTERN AIRLINES

By Martin Merzer

Published: June 27, 1983

In trying to describe what he and his company have been through in recent months, Eastern Airlines Chairman Frank Borman uses words like “turmoil” and “adversity” and “trauma.”

In trying to describe what could have happened, he uses words like “bankruptcy” and “doomsday.”

At one point, Borman says, he considered filing a bankruptcy petition to reorganize the company. Then, some of his labor- relations problems would be dumped in the lap of a federal judge.

Later, a financial crisis appeared so grim that even a carefully honed “doomsday” corporate survival plan was set aside. It was deemed inadequate.

Later still, faced by a looming cash shortage, Borman says he could identify only two options if his employes failed to accept wage concessions demanded by bankers in return for new loans:

Either he could stand by helplessly and watch Eastern’s operations wither and eventually die from a lack of cash, or he could simply shut down the company. He leaned toward the second option.

After all, the situation could hardly have been worse.

Eastern’s employe groups were at war with management and at war with each other.

The company was running out of cash and facing intransigent lenders.

An Eastern jumbo-jetliner had nearly ditched off Miami because of an in-house maintenance error. In addition, two Eastern flights had been hijacked to Cuba.

Sales were off. Losses were mounting at the rate of $1 million a day. Morale was terrible.In searching for a comparison, in trying to explain just how ominous the situation was just a few weeks ago at South Florida’s largest corporate employer, Borman reaches back to the 1967 flash-fire that killed three Apollo astronauts.

Although Borman spent eight years as an astronaut and traveled to the moon, he rarely mentions his earlier career. He made an exception last week during his first extended press interview since Eastern plunged into the maelstrom of crisis four months ago.

“The whole Apollo program was destabilized after the tragedy>,” he says. “We questioned ourselves; we questioned the program; we questioned our competency. I was right in the middle of that.

“This period at Eastern has been almost like deja vu for me,” Borman says, a humorless smile flashing across his face. “I felt like I had been there before.”

Now, Borman says, the situation is much better.

Most of Eastern’s labor relations problems are under control, he says. Most employes have reluctantly accepted new wage concessions, and morale is recovering. New loans should be forthcoming this Wednesday, June 29, one day before the deadline.

“That will allow us to pay the bills on the 30th,” Borman says.

He says that passenger reservations are strong this summer, and -- other than an effort to modestly increase fares -- the company plans very few changes to its current operating strategy.

“I believe that we are over the hump,” he says. “I feel confident of the future.”

Analysts tend to agree.

Robert Joedicke, an airlines analyst for Lehman Bros. Kuhn Loeb, agrees that Eastern is one of the leaders in the current attempt to eliminate some unprofitable discount fares, and he says that the entire industry seems poised for an upturn.

“If you buy that we’re in an economic upturn, as the statistics would indicate, then the traffic will recover,” Joedicke says. “This obviously has to be a key factor in his scenario, and I don’t think he’s unrealistic in expecting an improvement.”

Michael Derchin, an airlines analyst with First Boston Corp., predicts that Eastern will narrow its losses this year and report a respectable profit during 1984.But Eastern’s brush with corporate disaster is still fresh in Borman’s mind, and although the subject is painful, he speaks candidly of just how close he was to administering over the bankruptcy -- even, possibly, the demise -- of Eastern Airlines.

He says that a Chapter 11 bankruptcy petition, which allows reorganization of a company under court-administered protection from creditors, was considered in March.

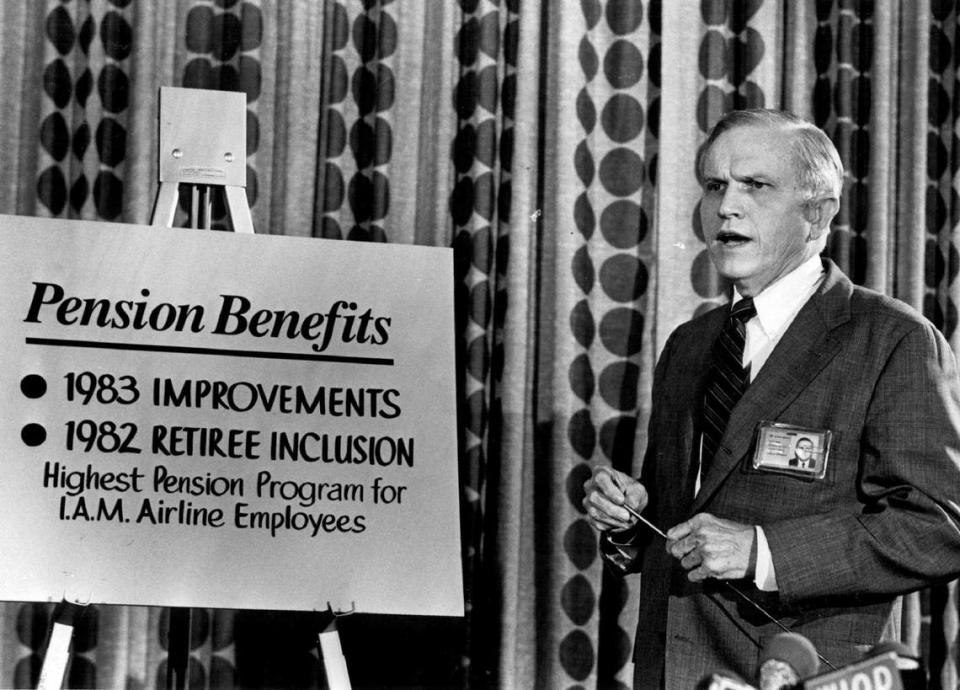

Eastern was faced at the time with a strike threat by its largest union, the International Association of Machinists (IAM). The union, which represents about 13,500 Eastern employes, was demanding pay and benefit increases that Borman says he could not afford.

“We examined the prospect

of declaring bankruptcy> ... and then just allowing a judge to impose a suitable wage solution,” Borman says.

But how do you persuade passengers and travel agents to give their business to an airline in bankruptcy proceedings?

“I became convinced after the briefings that we had with the legal experts that it would be impossible to run an airline under the protection of Chapter 11,” Borman says. “I wasn’t about to try it.”

After winning a few compromises from the union, the company agreed to a contract that would raise its costs by $170 million. Eastern -- which lost $74.9 million last year and another $60.7 million during the first three months of this year -- couldn’t afford that, either, and was immediately plunged into a cash crisis.

Without new loans, Eastern would be unable to meet its payroll or pay many other bills on June 30, the company said.

But the banks already had frozen Eastern’s credit line and were unwilling to thaw it until much of the work force agreed to new wage concessions.

Eastern’s 37,200 employes (including 12,000 in South Florida) had just been released from a five-and-a-half-year Variable Earnings Program, under which they returned 3.5 per cent of their pay to the company.Most workers recently accepted the new concessions, though it was a tough sell. And as a result, Eastern should be able to save $200 million in payroll costs by the end of next year, Borman says.

More important, the lenders are expected to give Eastern enough credit this week to keep the airline solvent through December. By then, Borman says, the company’s financial status should be secure enough that it won’t have to humble itself again before the lenders.

But if the employes had balked at the concessions, Borman says, his choices would have been limited to watching Eastern die a slow death through gradual cash starvation or a more rapid one at his own hand.

“That would have led to a decision that would have required a lot of thought -- whether it would have been better to just shut it down, a la Braniff,” he says.

Borman already had dusted off his “doomsday plan” -- a long-standing survival plan that would slash the airline’s operations -- and found it lacking.

“When we looked at it, it didn’t make any sense at all,” he says. “The doomsday situation -- it’s very hard to take a major airline with the overhead and debt-structure that this airline has and cut it by one-third. I don’t think it’s ever been done before.”

During the interview, Borman also:

- Defended his stance in negotiating with the machinists.

During the talks, he had maintained that Eastern would rather take a strike than cave in to the IAM. Later, company officials said they would have done almost anything to avoid a strike.

Although non-union employes later criticized Borman for settling with the union, he said that the negotiating ploy had resulted in some concessions from the IAM. A strike would have bankrupted Eastern in 12 days, he said.

“If I’d been faced with no change on the part of the other side, we would have had to take the strike> and that would have been the end of the game...,” he said. “It would have been a lost cause. Going down in a blaze of glory because your cause is lost, that was not something that was acceptable to me.”

- Said that the recent near-ditching of the Eastern L1011 after all three engines ran out of oil and failed was “perhaps the most adverse thing in our relationship with the public” and cost the company dearly in canceled reservations.

But he defended the decision not to fire the two mechanics involved.

“We investigated and found there were problems of our own making as well as theirs,” Borman said. “I think we did what was right. I’d rather be doing what’s right than what’s perceived as popular, especially when people’s jobs and lives are involved.”

He said the company’s procedures have been improved.

“The No. 1 goal of this airline is safety,” Borman said.

- Reiterated that he has no plans to resign, although he says he has received attractive job offers from non-airline companies he would not identify.

“It never entered my mind to quit under these circumstances,” said Borman, 55. “I like to think that we have threaded our way through this mess as well as anybody could have.

“I had a lot of people who said, ‘You’re wasting your time down there in a hopeless situation. Come join us and we’ll double your salary.’

“So, aside from the people who suggested I quit because I was no damned good, there were a lot of people who suggested I quit because I had a hopeless situation.

“But I have no plans to leave. Frankly, I enjoy the airline.... I’m not about to retire to some gilded cage. I don’t play golf. I don’t play tennis. I don’t drink. I enjoy my work.”

THE END OF EASTERN AIRLINES

Published Jan. 19, 1991

Eastern Airlines shut down late Friday, ending a 62-year run as one of America’s principal air carriers and a decade as one of its most troubled corporations.

Eastern, crippled by airline deregulation, poisonous labor- management relations and a public that no longer trusted the carrier, simply ran out of cash. The airline was losing $2.5 million a day. In the past decade, it had lost more than $2.5 billion. And Martin Shugrue, the court-appointed trustee running Eastern, knew he couldn’t get any more money from the bankruptcy court that had supported the airline since it filed for protection 22 months ago.

Eastern announced at 9 p.m. that it would cease operations at midnight. Most of its 18,500 employees, including about 7,000 in South Florida, have no job today.

“I’m not shocked,” said Willie Mitchell, 50, a baggage agent who has worked with Eastern for 23 years. “We just haven’t had enough passengers to pay our bills. We knew it was imminent; we just didn’t know when.”

Most were notified of the news late Friday. In an electronic message to employees, Shugrue said: “Today I feel like the football player who, after an especially tough loss, commented on that particular day that his team didn’t lose — rather they simply ran out of time. “Time and a combination of events over which we had no control were in the end, simply too much for Eastern to overcome.”

Eastern pilots flew most of the 800 regularly scheduled flights Friday before getting orders to park the silver-and-blue planes at maintenance bases in Atlanta and Miami. One captain in Atlanta, after hearing news of the shutdown, walked off the plane as passengers waited for what they were told was a maintenance problem.

At Miami International, the last Eastern flight departed at 8:45 p.m. to New York’s La Guardia International Airport. It left on time. At Eastern counters, customers lined up, awaiting refunds on tickets for future travel. More than 1,000 employees, including reservation agents and some managers, will keep working to maintain planes and other assets until they can be sold or disposed of.

In Washington, D.C., Eastern notified members of Florida’s congressional delegation of the impending shutdown late Friday afternoon, just in case they were booked on Eastern.

Once South Florida’s pre-eminent corporation, Eastern died of exhaustion from fighting too many battles during the past decade. It borrowed heavily to buy planes in the early 1980s, crippling it with debt. Eastern never developed the transcontinental route system needed to compete in an era of megacarriers. And management and labor never learned to work together.

Even as Eastern was put to its death, union workers put the blame squarely on Frank Lorenzo, the former chairman of Texas Air who acquired Eastern in 1986. Three years later, the unions staged a massive strike that put the airline into bankruptcy and eventually led to Friday’s closing.

“It’s a sad day,” said Charles Bryan, who heads Eastern’s machinists union. “What’s happened is a tragedy. If there’s a lesson to be learned by corporate America, it proves that union busting is bad business.”

Eastern shut down one day after oil prices took their steepest drop ever. The sharp increase in fuel prices caused by the Persian Gulf crisis was the final, fatal, blow. Fuel costs, combined with declining passenger travel last year, made 1990 the worst year in history for the airline industry. But Eastern was less able than its competitors to withstand the losses, and periodic rumors of its imminent liquidation scared even more passengers away.

The decision to shut down the airline was tentatively made Jan. 11 in Bankruptcy Court Judge Burton Lifland’s chambers in New York City, said a source familiar with Eastern’s bankruptcy.

Shugrue told the judge that Eastern was running short of cash but was negotiating with an interested buyer. He then agreed that if he could not bring in a firm proposal to sell the airline by midnight Wednesday, it would be shut down two days later. The proposal never came. An industry source said Shugrue had been negotiating with British Air.

On Thursday, Eastern began planning to shut down. A day earlier, Lifland agreed to give Shugrue enough money to shut the airline down, the source said. A liquidation plan had been drawn up last fall, but few details were available Friday. Shugrue could not be reached for comment Friday evening.

Several creditors failed to return phone calls. Eastern will try to sell its remaining airplanes, routes and airport facilities. A source close to the company said, “We’ve been working on deals, and some are agreed to” but declined to be more specific.

United Airlines has been negotiating to buy gates at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago and at Los Angeles International Airport, as well as takeoff and landing rights at O’Hare. In addition, Delta Air Lines informed the bankruptcy court in early October that it is interested in paying $30 million for about a third of Eastern’s 50 gates at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta.

Eastern gradually has been selling off assets since it filed for bankruptcy protection five days after the March 4, 1989, strike by its machinists, pilots and flight attendants.

The airline has lost about $1.3 billion since then, including about $1 billion that Lifland allocated from the bankruptcy escrow account. In November, Lifland gave Eastern $135 million over the objections of the airline’s creditors. It was the first time the creditors had asked Lifland to shut the airline down. He declined.

That was the last time Eastern received cash from the court, and the money is nearly gone.

Sources close to the company said the balance stood at about $40 million in mid- January. But it will take whatever is left and even more to dismantle the airline.

The cost of shutting down Eastern has been estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars — some employees must stay on the payroll while assets are sold. Frank Borman, the former astronaut who ran Eastern Airlines for 13 years, described its collapse Friday as “one enormous tragedy.”

“My heart is wrenching in learning that the end has come,” he said from his office in Las Cruces, N.M., where he moved after resigning from Eastern in 1988. “It’s like a person dying. It’s very sad.

“The real tragedy,” he said, “is the fate of the nonunion people who were so very loyal. No one gave it a harder effort than those people did, and they’re the people who will be hurt the most.”

In early 1986, Eastern’s machinists union refused to go along with Borman’s plea for a 20 percent pay cut. That dispute was the catalyst for the sale of Eastern to Lorenzo’s Texas Air Corp. Lorenzo did little to solve — but much to aggravate — Eastern’s labor problems. He also moved profitable assets from Eastern to his other carrier, Continental Airlines, thereby further weakening Eastern.

Mary Jane Barry, president of the flight attendants union, said: “Eastern management, led by Frank Lorenzo, chose a course of action that guaranteed disaster. Lorenzo’s team improperly transferred millions in assets to Continental Airlines, fired long-term employees and provoked a strike as a final strategy to destroy the work force.”

When the unions joined in a massive strike, the clock began running on Lorenzo’s final days at Eastern, which filed bankruptcy five days later. Thirteen months after that, Eastern’s unsecured creditors convinced the bankruptcy court to replace Lorenzo with Shugrue. Shugrue was an inspirational leader who sought to lure passengers back with a series of frank TV advertisements, in which he starred, and an innovative plan to sell first-class seats for coach fares.

Both raised hopes, but too many forces worked against him.

In his last public appearance before the shutdown, Shugrue told a Washington, D.C., gathering on Tuesday: “Whether we make it or not, our strides have been remarkable.”