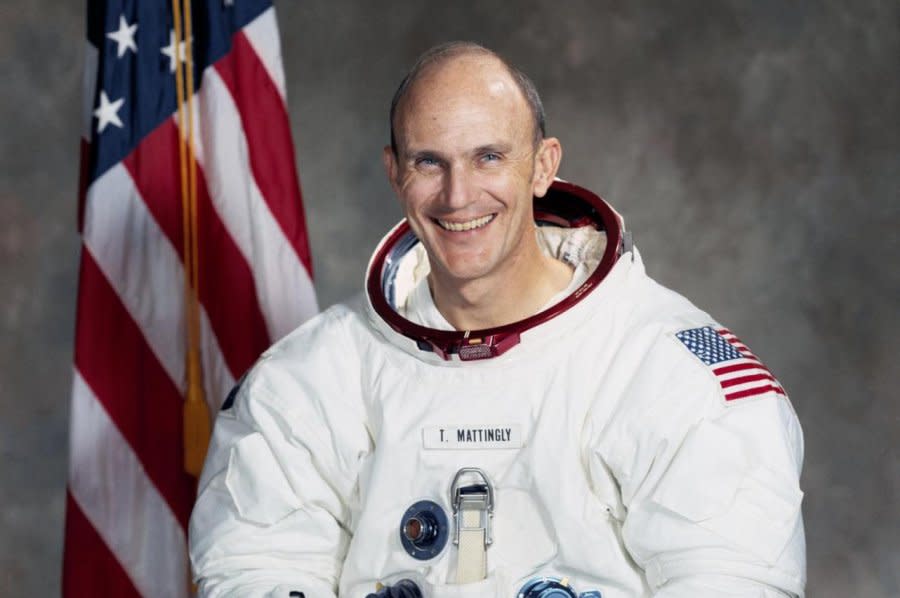

Astronaut Ken Mattingly, who flew to the moon on Apollo 16, is dead aged 87

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nov. 2 (UPI) -- Thomas K. Mattingly, the U.S. astronaut who circled the moon as command module pilot on NASA's Apollo 16 mission, is dead at age 87, the space agency announced Thursday.

"We lost one of our country's heroes on Oct. 31. NASA astronaut TK Mattingly was key to the success of our Apollo Program, and his shining personality will ensure he is remembered throughout history, NASA said in a statement."

Mattingly was heralded as a skilled pilot and was known for his accomplishments while in control of the command module for the Apollo 16 mission that landed on the moon in 1972. Astronauts collected samples of the lunar highlands during that mission as well as achieving other objectives in the early days of the U.S. space program.

"NASA astronaut TK Mattingly was key to the success of our Apollo Program, and his shining personality will ensure he is remembered throughout history," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said.

Mattingly was perhaps best known for being removed from the ill-fated Apollo 13 crew 72 hours before its scheduled launch. He was replaced by fellow astronaut Jack Swigert at the last moment after exposure to German measles.

56 hours after take off, the No. 2 oxygen tank exploded on the craft, which caused tank No. 1 to fail as well. "Houston, we've had a problem," fellow astronaut Jim Lovell famously radioed to mission control.

While not onboard the spacecraft, Mattingly would play a critical role in the Apollo 13 mission and the fate of Lovell and fellow crew members Swigert, and Fred Haise.

"He stayed behind and provided key real-time decisions to successfully bring home the wounded spacecraft and the crew of Apollo 13," Nelson said in the statement.

Mattingly attended many of the Apollo 13 emergency meetings, offered advice and gave controllers ideas on how to save electrical power in the spacecraft.

Mattingly downplayed his efforts in coaxing the craft back to Earth. "I didn't play any role," he said in an interview with NPR. "I was the observer. The people that played roles and in bringing that stuff together deserve a lot of credit."

Mattingly was an aeronautical engineer who had a love of technical things, but also seemed to have a flair for the dangerous and dramatic. He was a Navy pilot who took off and landed jets on aircraft carriers and went on to become an astronaut in 1966 when NASA selected him to be one of 19 students that year in the nascent space program.

He was instrumental in three of the most important Apollo missions there had been to date.

He was a member of support crews for Apollo 8, which was the first mission to go to the moon, and Apollo 11, which was the first mission that put a man on the moon. Apollo 13 would have been his first trip to space before he was scratched due to the measles exposure.

"Was I disappointed? Oh you bet!" he said in 2017 during a visit to Des Moines Area Community College in Iowa. "There has never been anything in Shakespeare or any other publication that could throw a fit or feel sorry for yourself like I did."

Following his Apollo days, Mattingly helped launch NASA's space shuttle program and commanded two missions. He retired from the space agency in 1985 and from the Navy the following year, finishing his military career as a rear admiral.

He later said commanding the space shuttle missions were the proudest moments of his career with the agency.

"For me it was the opportunity of a lifetime in my career to be able to be with a project from go-ahead to turning it over as an operational product," he said.

Over time, Mattingly began to question the costs of human space exploration in light of technological advancements. He told NPR that robots are so good now, NASA needs to define questions that can only be answered by a human presence.

"Would it be exciting? Oh sure it would," he said, "but how many billions of dollars are we going to spend on exciting things for one or two people to enjoy? And if it doesn't lead anywhere."

Mattingly continued to speak publicly about the issue into his 80s.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story gave an incorrect date for when Thomas Mattingly became an astronaut. He jointed the astronaut corps in 1966.