Astronomers discover 3 previously unknown moons orbiting planets in our solar system

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Astronomers have discovered three previously unknown moons around Uranus and Neptune, the most distant planets in our solar system.

The find includes one moon spotted orbiting Uranus — the first discovery of its kind in more than 20 years — and two detected in Neptune’s orbit.

“The three newly discovered moons are the faintest ever found around these two ice giant planets using ground-based telescopes,” said Scott S. Sheppard, astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science, in a statement. “It took special image processing to reveal such faint objects.”

The revelations will be helpful for missions that may be planned to explore Uranus and Neptune more closely in the future, a priority for astronomers since the ice planets were only observed in detail with Voyager 2 in the 1980s.

The three moons were announced on February 23 by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center.

Finding faint moons

The newfound Uranian moon is the 28th to be observed orbiting the ice giant and is also likely the smallest, measuring 5 miles (8 kilometers) across. The moon, called S/2023 U1, takes 680 Earth days to complete one orbit around the planet. In the future, the tiny satellite will be named after a Shakespearean character, in keeping with the tradition of Uranus’ moons bearing literary names.

Sheppard spotted the Uranian moon in November and December while carrying out observations using the Magellan telescopes at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. He worked with Marina Brozovic and Bob Jacobson of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to determine the moon’s orbit.

The Magellan telescopes also played a key role in helping Sheppard find the brighter of the two new Neptunian moons, S/2002 N5. The Subaru telescope, located on Hawaii’s dormant volcano Mauna Kea, helped Sheppard and his collaborators astronomer David Tholen at the University of Hawaii, astronomer Chad Trujillo at Northern Arizona University, and planetary scientist Patryk Sofia Lykawka at Kindai University in Japan, to focus in on the other extremely faint Neptunian moon, S/2021 N1.

Both moons, which bring the total of Neptune’s known natural satellites to 18, were first spotted in September 2021, but required follow-up observations with different telescopes over the past couple of years to confirm their orbits.

“Once S/2002 N5’s orbit around Neptune was determined using the 2021, 2022, and 2023 observations, it was traced back to an object that was spotted near Neptune in 2003 but lost before it could be confirmed as orbiting the planet,” Sheppard said.

The bright S/2002 N5 moon is 14 miles (23 kilometers) in diameter and takes nearly nine years to complete an orbit of Neptune, while faint S/2021 N1 is about 8.7 miles (14 kilometers) across and has a lengthy orbit of about 27 years. Both will eventually get new names that reference the Nereid sea goddesses from Greek mythology. Neptune was named for the Roman god of the sea, so the planet’s moons are named after lesser sea gods and nymphs.

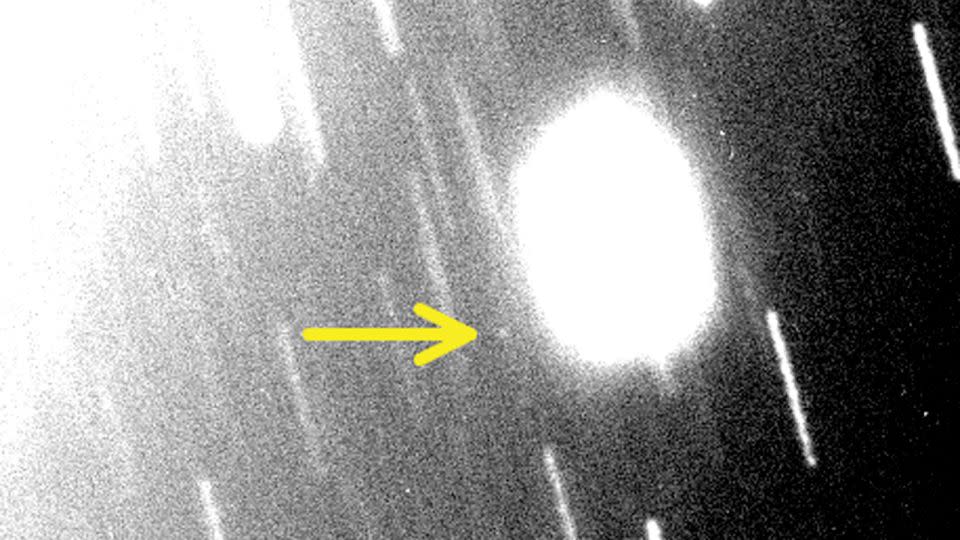

Finding all three moons required dozens of brief, five-minute exposures over the course of three or four hours on different nights.

“Because the moons move in just a few minutes relative to the background stars and galaxies, single long exposures are not ideal for capturing deep images of moving objects,” Sheppard said. “By layering these multiple exposures together, stars and galaxies appear with trails behind them, and objects in motion similar to the host planet will be seen as point sources, bringing the moons out from behind the background noise in the images.”

A chaotic solar system

By studying the distant, angular orbits of the moons, Sheppard hypothesized that the satellites were pulled into orbit around Uranus and Neptune due to the gravitational influence of the giant planets shortly after they formed. The outer moons orbiting all the giant planets across our solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — share similar configurations.

“Even Uranus, which is tipped on its side, has a similar moon population to the other giant planets orbiting our Sun,” Sheppard said. “And Neptune, which likely captured the distant Kuiper Belt object Triton — an ice rich body larger than Pluto — an event that could have disrupted its moon system, has outer moons that appear similar to its neighbors.”

It’s possible that some of the moons around the giant planets are fragments of once larger moons that collided with asteroids or comets and broke apart.

Understanding how the giant planets captured their moons helps astronomers piece together the chaotic early days of our solar system.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com