An asylum seeker is freed, then rearrested, as ICE makes Cubans languish in detention

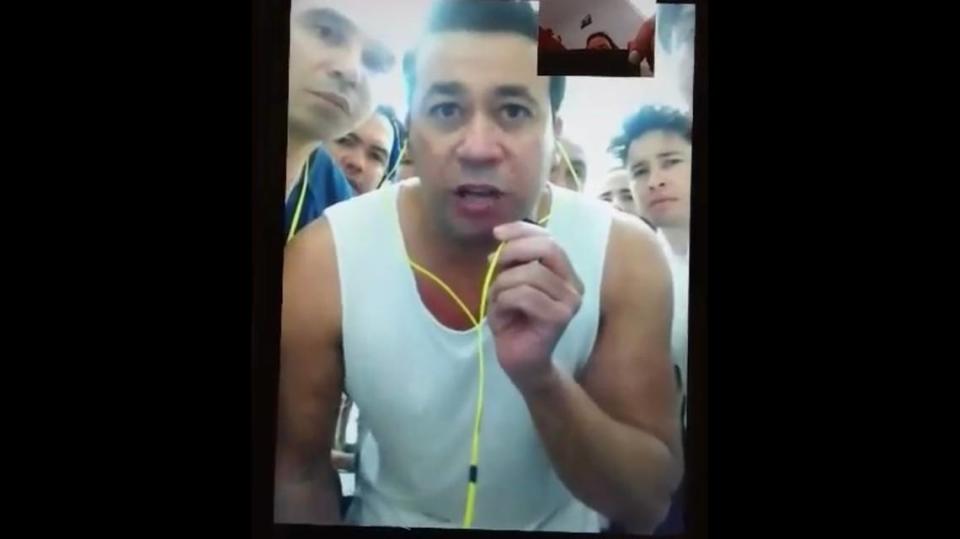

When the news came that Dayron Naranjo-Alvarez would finally be a free man, his 60-plus fellow detainees broke out in cheers.

Within minutes, the announcement that the Cuban asylum seeker would be released from Louisiana’s Jackson Parish Correctional Center spread like ripples in a pond, across WhatsApp chat rooms in his native Cuba and Facebook groups across the United States.

Tears of joy interspersed with mid-air high-fives filled the correctional center.

The celebratory moment — which happened during a live video interview with the Miami Herald last week — became a symbol of hope for the 1,800 other Cuban nationals serving years in confinement while awaiting deportation by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“I can’t believe it. I’m giddy,” he said in Spanish as he rushed to finish the interview. “I gotta go now and pack now before ICE changes their mind,” he joked.

That’s exactly what ICE did — five days after his Oct. 21 release, records show.

Before dawn, agents surrounded the Kentucky home of a friend of Naranjo-Alvarez — exactly where he said he’d be staying — and told him to come outside. Goodbye, freedom.

“He cooperated but was crying and begging them not to take him back there,” his twin brother, Danny Naranjo-Alvarez, said late Monday. “They said there was some sort of error with his release, that he shouldn’t have been released and that he’s being deported. So they took him away again.”

The brother paused.

“But this is not an error — it’s terror.”

A day after this story published, ICE told the Herald in an email that Naranjo-Alvarez was “erroneously released... from an ICE facility in Louisiana.”

“ICE re-arrested him Oct. 27 in Louisville, Kentucky,” the agency wrote. “He will remain in ICE custody pending removal from the United States.”

Desperate to deport

Under the longtime policy “wet foot, dry foot,” a Cuban asylum seeker who made it to U.S. soil would be released into the community right after being processed. That policy was phased out under the administration of President Barack Obama. Other policies favoring Cubans though remain in place — they are just not being applied uniformly under the administration of President Donald Trump.

For instance, under the United States’ convoluted immigration policies, people who are subject to a final order of deportation — as Naranjo Alvarez was — can apply after 90 days after the removal order is final to be released in exchange for agreeing to report for subsequent status hearings. That procedure was established under a 2001 Supreme Court ruling (Zadvydas v. Davis).

Successfully applying for release may hinge on having access to a lawyer, not a given in rural Louisiana. Cuban detainees who do manage to parole out have an advantage that other nationalities do not: After one year and a day on parole status, they are able to become legal residents.

Under Trump, ICE appears to be thwarting the intent of that provision by simply not releasing Cuban asylum seekers, thus never starting the clock on the one-year-and-a-day timetable, immigration advocates say.

Further prolonging the Cubans’ legal limbo is the fact that Cuba is picky and its acceptance patterns can be “arbitrary,” according to Cuba policy experts.

“Cuba accepts who they want to accept and there’s no rhyme or reason. It’s always been challenging to deport someone back,” said Juan Carlos Gomez, director of Florida International University’s immigration law clinic.

The last deportation flight to Cuba was in late February when ICE sent 119 deportees home. Shortly after that, international borders closed because of the pandemic. Cuba, like other countries, stopped accepting deportees as the number of COVID-positive cases soared in ICE detention.

However, while some countries have begun accepting deportees with a clean bill of health, Cuba has refused.

Gomez, who has been practicing immigration law for decades, said the health crisis has made the United States “more desperate to deport.”

This past summer, Ryan M. Kaldahl, the acting assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Legislative Affairs, made that urgency clear in a letter to the Cuban government.

“As of early July, there is a growing backlog of ...Cubans in ICE custody, including 44 individuals who have been in custody for longer than 90 days, and who will soon be legally eligible for release if they are not deported,” he wrote in a letter dated Aug. 13.

It’s unclear how much those numbers have increased since July. The State Department declined to comment. Under the condition of anonymity, two officials with the Department of Homeland Security told the Miami Herald that negotiations with Cuba over a resumption of deportation will begin as early as Nov. 1.

“That’s why there was an urgency to arrest people like [Naranjo-Alvarez] again,” said one of the two DHS officials. “The agency realized that they actually will be able to deport him soon so they retrieved him again.”

Records show Naranjo-Alvarez is currently being held at Kentucky’s Boone County Jail, which doubles as an ICE detention center.

Naranjo-Alvarez crossed the U.S. southern border with his three brothers in September 2019. Hours after crossing, the siblings checked themselves in with U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. They were immediately detained. As evidence of the arbitrary nature of U.S. immigration policy, two of the brothers have been deported, Dayron’s twin was released in February before the pandemic, while Dayron was kept in custody — until he was, confusingly, released then re-detained.

Screams in the night

Edwin Rodriguez, a Cuban who remains in ICE detention in Louisiana, says Naranjo-Alvarez’s rearrest has given him and some of his fellow detainees nightmares.

The insomnia and depressive episodes aren’t new for Rodriguez, who says crying “has become routine.”

“I sleep on the top bunk so they can’t really see me as much,” he said. “It’s not just me, it’s the majority of us. You can hear the sniffles and there’s always someone that breaks. Some scream or begin pacing back and forth.”

Rodriguez is one of almost 1,800 Cubans now being held in ICE detention facilities across the country. Like Naranjo-Alvarez, Rodriguez arrived and checked himself in at the southern border in early 2019 with the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. That’s when he was taken into custody and sent to U.S. detention in Louisiana, where he has remained.

“Louisiana is a black hole for Cubans. That’s why the government mostly sends them there,” said Gomez, the director of FIU’s immigration law clinic.

He added: “They’ve been sending Cubans to places where they know they will not be granted asylum — middle-of-nowhere places in Louisiana and Georgia where they have very low asylum-approval rates and where issues of Cuba are not known.”

It matters very much in which region of the courts an asylum seeker ends up. Federal data show detainees in Georgia and Louisiana have a 90% chance of getting denied asylum, depending on the judge assigned to the case. The Miami immigration court has an 85% denial rate.

Detainees in New York and San Francisco have higher chances of being granted asylum. The denial rate there is in the 20% to 30% range.

“But they won’t send them there. Heck, they won’t even send them to detention in Miami because Miami knows — we know the Cuban community because we are the Cuban community,” said Randy McGrorty, a longtime Miami immigration lawyer and executive director of Catholic Legal Services, a nonprofit under the Archdiocese of Miami that helps Cuban immigrants obtain asylum.

McGrorty, part of a legal team that is preparing a Louisiana lawsuit against ICE, says the government is holding the detainees indefinitely until they get a guarantee from Havana that deportees will be accepted.

“They are being held basically forever — or until Cuba can take them back, which could be never, or tomorrow,” said Ross Militello, who worked as an attorney for ICE up until last year, and currently runs his private immigration practice out of Miami and San Francisco. “It’s an abyss.”

According to the 2001 Supreme Court ruling, detention is no longer “presumptively reasonable” after the 180th day and a detainee can challenge his or her detention in court. However, access to a lawyer is close to impossible for immigrants with little to no income who are being held in remote facilities. Unlike the U.S. criminal justice system, ICE detainees don’t have the right to legal counsel, such as a public defender.

One way for ICE to avoid releasing detainees: If the agency labels the detainee a “flight risk” or a “danger” to the community.

“People should be removed [deported] within 90 days. After that, the government should release them either because they are not a flight risk or danger or because 180 days have passed and removal is not reasonably foreseeable,” Argueta said. “Zadvydas looked at what is a reasonable time to hold someone while trying to remove them and said it can’t be indefinite and six months is presumptively the constitutional limit.”

The ability to apply for a green card a year and a day after being paroled is a special benefit enjoyed under the Cuban Adjustment Act.

“That’s why they are not releasing Cubans,” Militello said. “It’s a loophole. Today, Cubans are the only people on earth that get a pathway to citizenship post parole. Instead, ICE has been denying their parole, calling them a ‘flight risk.’”

Militello, who is representing some immigrants pro bono, said detention facilities in the states of Louisiana and Georgia “were built there for a reason.”

“It’s not an immigration hot spot so there are very few attorneys,” he said.

In Georgia, more than 100 Cubans are being held past the 180-day mark; some have been in detention for up to two years, according to attorneys at the Southern Poverty Law Center, who say the government is violating its own policies by not releasing detainees after the 180-day cut-off time.

U.S. laws and policies “do not permit indefinite detention,” said Erin Argueta, an attorney for the SPLC. “ICE keeps violating the parole directive and are currently violating provisions and the Constitution regarding what should happen when ICE is unable to remove someone with a final order.”

Mich Gonzalez, another attorney working with Argyuta, said Cubans in less rural areas are getting out on parole as they should be.

“It just points out the wide discretion that ICE has,” Gonzalez said.

In the past few years, the SPLC along with the American Civil Liberties Union won two federal lawsuits that sought to have five ICE field Offices serving broad areas, including Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee, Michigan, Ohio, New Mexico, Texas, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Los Angeles, comply with a 2009 management directive that guides the agency’s practices. The directive sets policies for determining whether an immigrant has a credible fear of persecution in their home country.

“It just shows that ICE is legally bound by this directive,” Gonzalez said. “However they still violate it, especially in certain areas.”

Although deportations to Cuba have been on hold, that is likely to change, said Luis Miguel Diaz, another asylum seeker in Louisiana.

“That time is coming soon; they told us yesterday to get ready,” Diaz said.

Chimed in another man in Spanish: ““This is not detention, this is kidnapping. We are being held hostage.”